Never-before-seen head of prehistoric, car-size 'millipede' solves evolutionary mystery

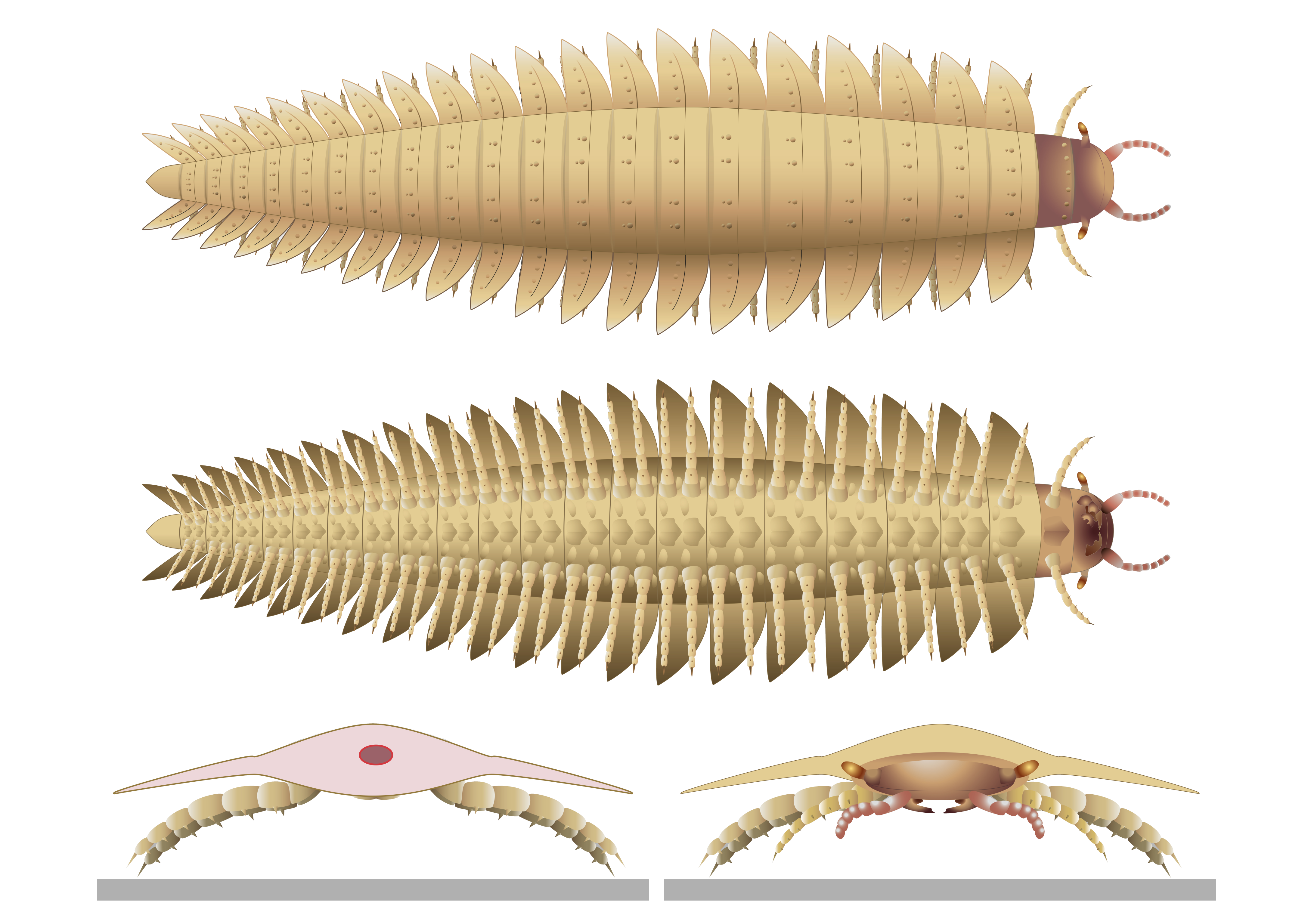

The fossil showed unique stalked eyes and centipede-like characteristics.

The face of a car-size, millipede-like creature — the largest arthropod ever to live — has finally been revealed thanks to two well-preserved fossils, a new study reports.

The arthropod, Arthropleura, lived in forests near the equator between 346 million and 290 million years ago, during the late Paleozoic era. In the oxygen-rich atmosphere at that time, Arthropleura could grow to a massive 8.5 feet (2.6 meters) long and weigh over 100 pounds (45 kilograms).

"Arthropleura … has been known since the 18th century, over 100 years, and we hadn't found a complete head," study first author Mickaël Lheritier, a paleontologist at Claude Bernard Lyon 1 University in France, told Live Science. "Now with the completed head, you can see the mandibles, the eyes, and these characteristics can [help us understand] the position of this [creature] in evolution."

The giant arthropod had perplexed paleontologists for decades. Arthropleura's body had characteristics like a millipede. But without the head, scientists couldn't understand the creature's relationship to modern arthropods like millipedes and centipedes. While these two modern creatures may look similar, they actually diverged about 440 million years ago, way before Arthropleura came around. Paleontologists wondered if Arthropleura was a member of the millipede group or the centipede group.

Arthropleura's family-tree controversy "features fierce debates about its affinities," James Lamsdell, a paleontologist at West Virginia University who was not involved with the study, wrote in an accompanying perspective published in the same journal. But with the discovery of an intact head, "the mystery of Anthropleura now appears solved."

Related: 7-foot-long arthropods commanded the sea 470 million years ago, 'exquisite' fossils show

The CT scans virtually uncovered the fossilized head of two juvenile Arthropleura discovered within rock in the Montceau-les-Mines Lagerstätte fossil site in France. The CT scans revealed unique stalked eyes jutting from the side of the head; gently curved antennae; and small, centipede-like mandibles. Together, these traits made up a confusing amalgamation of centipede- and millipede-like characteristics.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"These details, together, may appear to leave Arthropleura as much — if not more — a puzzle than before," Lamsdell said. "But the seemingly chimeric nature of Arthropleura is actually important evidence that may help answer a fundamental question regarding the [evolution of these species]."

Based on anatomical features, paleontologists ultimately grouped Arthropleura as most closely related to the millipede family. However, the stalked eyeballs have never been seen in the millipede or centipede families. Arthropleura has been widely considered terrestrial, but eyestalks are typically found in semiaquatic or fully aquatic animals, like crustaceans.

Because the head belongs to a juvenile, the explanation might lie in the animal's life stage, Lamsdell suggested. As juveniles, Arthropleura may have spent more time in the water, before losing the stalked eyes in adulthood. "The stalked eyes remain a big mystery, because we don't really know how to explain this," Lheritier said.

Sierra Bouchér is a Washington, D.C.-based journalist whose work has been featured in Science, Scientific American, Mongabay and more. They have a master's degree in science communication from U.C. Santa Cruz, and a research background in animal behavior and historical ecology.