Oldest tadpole on record was a Jurassic giant

The fossilization of the tadpole's "delicate structures," like its eyes and gills, allowed for a detailed analysis of the rare find.

While searching for dinosaur fossils in Argentina, paleontologists made an accidental discovery: the oldest tadpole ever found.

The fossil, unearthed in the La Matilde Formation in Patagonia, may finally settle a debate about frog evolution, the scientists reported Wednesday (Oct. 30) in the journal Nature.

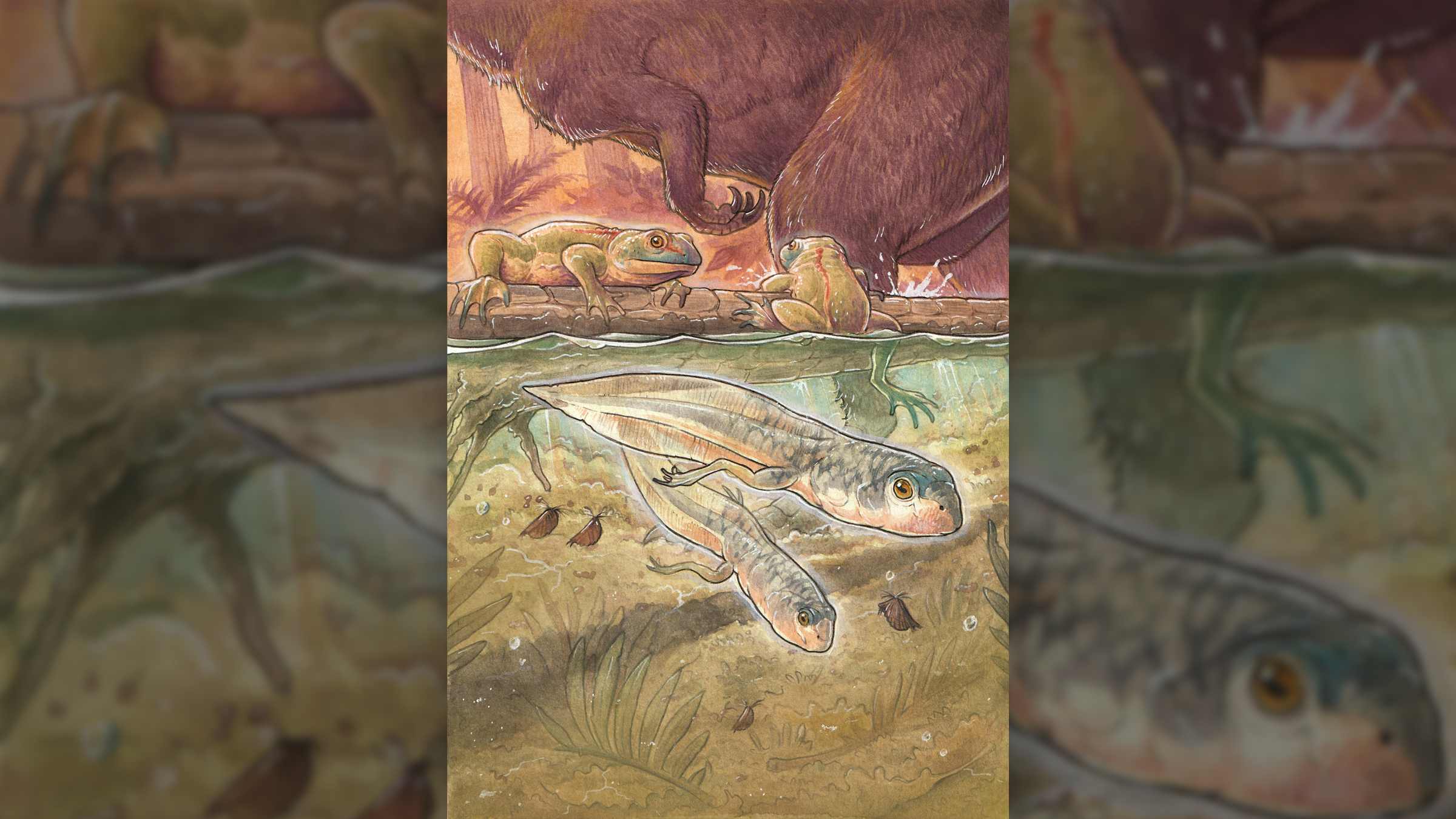

The fossil is a fantastically preserved specimen of the frog species Notobatrachus degiustoi, complete with imprints of soft tissues, including the animal's eyeballs, gills and nerves, according to the research.

The specimen dates to around 161 million years ago during the middle Jurassic. The next oldest tadpole had been dated to the early Cretaceous, 145 million to 100 million years ago. The newfound fossil is also the first ancient tadpole that has been matched to its adult counterpart in the fossil record. It may settle a debate about when the tadpole stage of frog development evolved.

"There are some researchers that state that probably the most [ancient] frogs didn't have a tadpole stage," said Mariana Chuliver, an evolutionary biologist at Maimónides University in Buenos Aires and first author of the paper. That's because the oldest frog fossil on record dates to the late Triassic (around 217 million years ago), tens of millions of years before the oldest known tadpole fossils. But by discovering this fossil, "we demonstrated that was not true," she said.

Related: Dinosaur-era frog found fossilized with belly full of eggs and was likely killed during mating

Generally, tadpole fossils are hard to come by, as the juvenile swimmers usually die while still in water. With scavengers ready to feast on fallen critters, the water can sometimes be a bad place for fossilization. In addition, tadpoles are made mostly of cartilage and soft tissue; they don't form the hard bones that fossilize more easily until adulthood.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Luckily, this tadpole is in an advanced stage of development," Chuliver told Live Science. The vertebrae of the tadpole had begun to ossify, allowing researchers to see the bumps and ridges of the spine that helped them identify the species and connect the tadpole to its adult counterpart.

"The most amazing thing for me is the preservation of such delicate structures," Chuliver said, "which is really hard to find in the fossil record." The size of the specimen was also helpful for identifying the species, she added. The tadpole was about 6 inches (16 centimeters) long — like a baseball with a 3-inch-long (7.6 cm) tail. The adult frog is just as big, which surprised the researchers.

"Both [juvenile and adult] stages being giant is really hard to find in nature today," Chuliver said. But for N. degiustoi, the ponds of the Jurassic had ample resources, and the tadpoles could afford a longer development time, she suggested.

However, other than its size, the body of the N. degiustoi tadpole is very similar to that of a modern tadpole. Imprints of spiny projections on the gills indicated that the tadpole likely even ate the same way modern tadpoles do, with a filter-feeding system that allows it to suck plankton, algae and detritus from the water around it. Considering these complex systems had already evolved in tadpoles 161 million years ago, tadpoles have likely been around just as long as adult frogs have, the researchers suggested.

Chuliver hopes to get more funding to return to the La Matilde Formation in search of more tadpoles to expand the fossil record.

Sierra Bouchér is a Washington, D.C.-based journalist whose work has been featured in Science, Scientific American, Mongabay and more. They have a master's degree in science communication from U.C. Santa Cruz, and a research background in animal behavior and historical ecology.