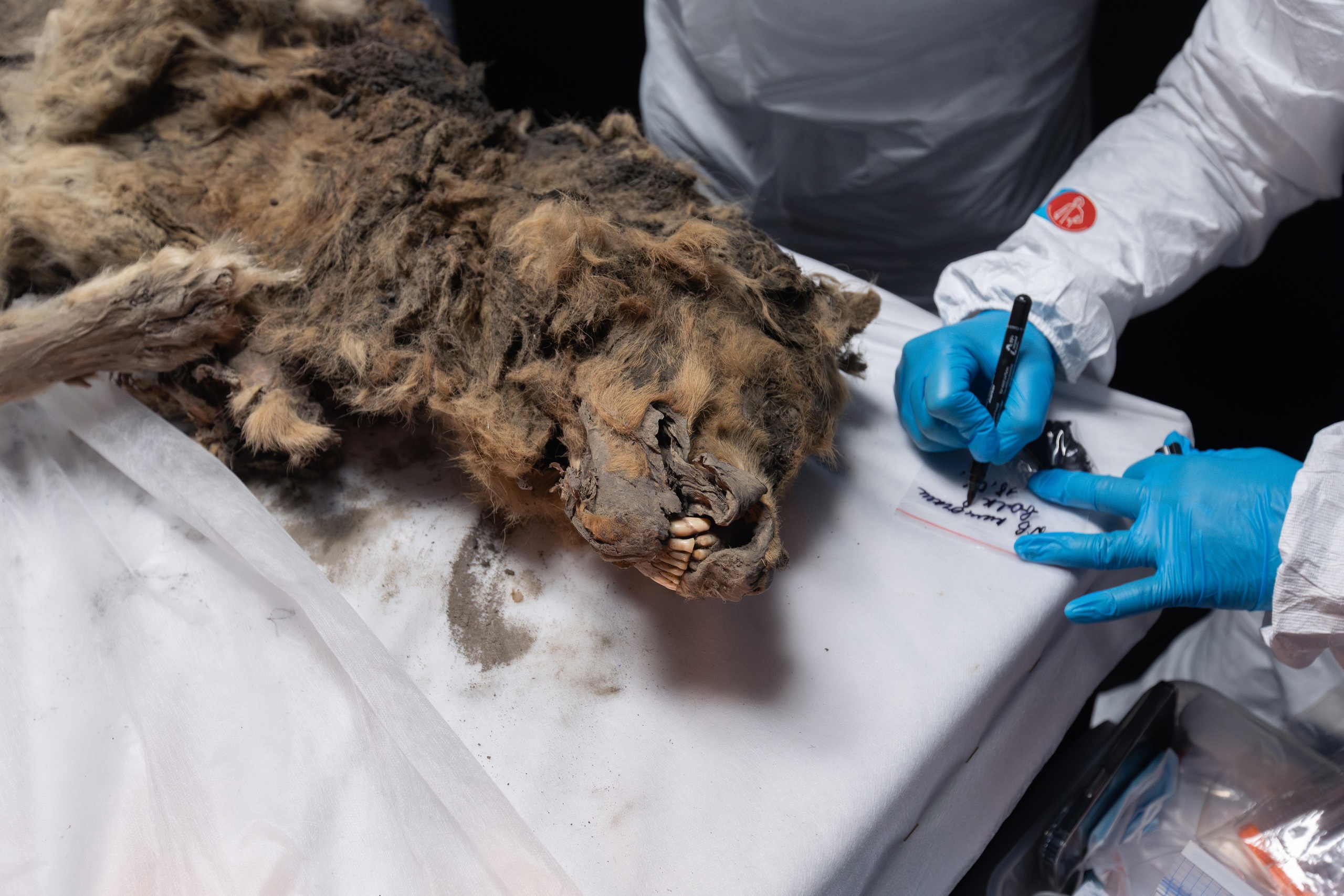

Stunning photos show 44,000-year-old mummified wolf discovered in Siberian permafrost

Scientists perform necropsy on an ancient wolf pulled from Russian permafrost that may still have prey in its stomach.

In a first-of-its-kind discovery, a complete mummified wolf was pulled from the permafrost in Siberia, after being locked away for more than 44,000 years. Scientists have now completed a necropsy (an animal autopsy) on the ancient predator, which was discovered by a river in the Republic of Sakha — also known as Yakutia — in 2021.

This is the first complete adult wolf dating to the late Pleistocene (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago) ever discovered, according to a translated statement from the North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk, where the necropsy was performed. The discovery, scientists say, will help us better understand life in the region during the last ice age.

Photos from the necropsy show the wolf's mummified body in exquisite detail. Animals are preserved in permafrost through a type of mummification involving cold and dry conditions. Soft tissues are dehydrated, allowing the body to be preserved in a frozen time capsule.

Researchers took samples of the wolf's internal organs and gastrointestinal tract to detect ancient viruses and microbiota, and to understand its diet when it died.

Related: Mummified mystery pup that died 18,000 years ago was a wolf

"His stomach has been preserved in an isolated form, there are no contaminants, so the task is not trivial," Albert Protopopov, head of the department for the study of mammoth fauna of the Academy of Sciences of Yakutia, said in the statement. "We hope to obtain a snapshot of the biota of the ancient Pleistocene."

He added the wolf, which tooth analysis revealed was male, would've been an "active and large predator," so they will be able to find out what it was eating, along with the diet of its victims, which "also ended up in his stomach."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Another key aspect of the necropsy is looking at the ancient viruses the wolf may have harbored. "We see that in the finds of fossil animals, living bacteria can survive for thousands of years, which are a kind of witnesses of those ancient times," Artemy Goncharov, who studies ancient viruses at the North-Western State Medical University in Russia, and is part of the team analyzing the wolf, said in the statement.

He said the research project will aid their understanding of ancient microbial communities and the role of harmful bacteria during this period. "It is possible that microorganisms will be discovered that can be used in medicine and biotechnology as promising producers of biologically active substances," he added.

The wolf necropsy is part of an ongoing project to study the wildlife that lived in the region during the Pleistocene. Other species examined include ancient hares, horses and a bear from the Holocene. The team plans to study the wolf's genome to understand how it relates to other ancient wolves from the region, and how it compares to its living relatives. The team now plans to start studying another ancient wolf discovered in the Nizhnekolymsk region of northeast Siberia in 2023.

Hannah Osborne is the planet Earth and animals editor at Live Science. Prior to Live Science, she worked for several years at Newsweek as the science editor. Before this she was science editor at International Business Times U.K. Hannah holds a master's in journalism from Goldsmith's, University of London.