Triassic amphibians the size of alligators perished in mass die-off in Wyoming, puzzling 'bone bed' reveals

The discovery of nearly 20 alligator-size amphibians that died together during the Triassic in what is now Wyoming is providing scientists important clues about these creatures' lives.

Around 230 million years ago, at least 19 alligator-size amphibians expired together on an ancient floodplain in what is now Wyoming.

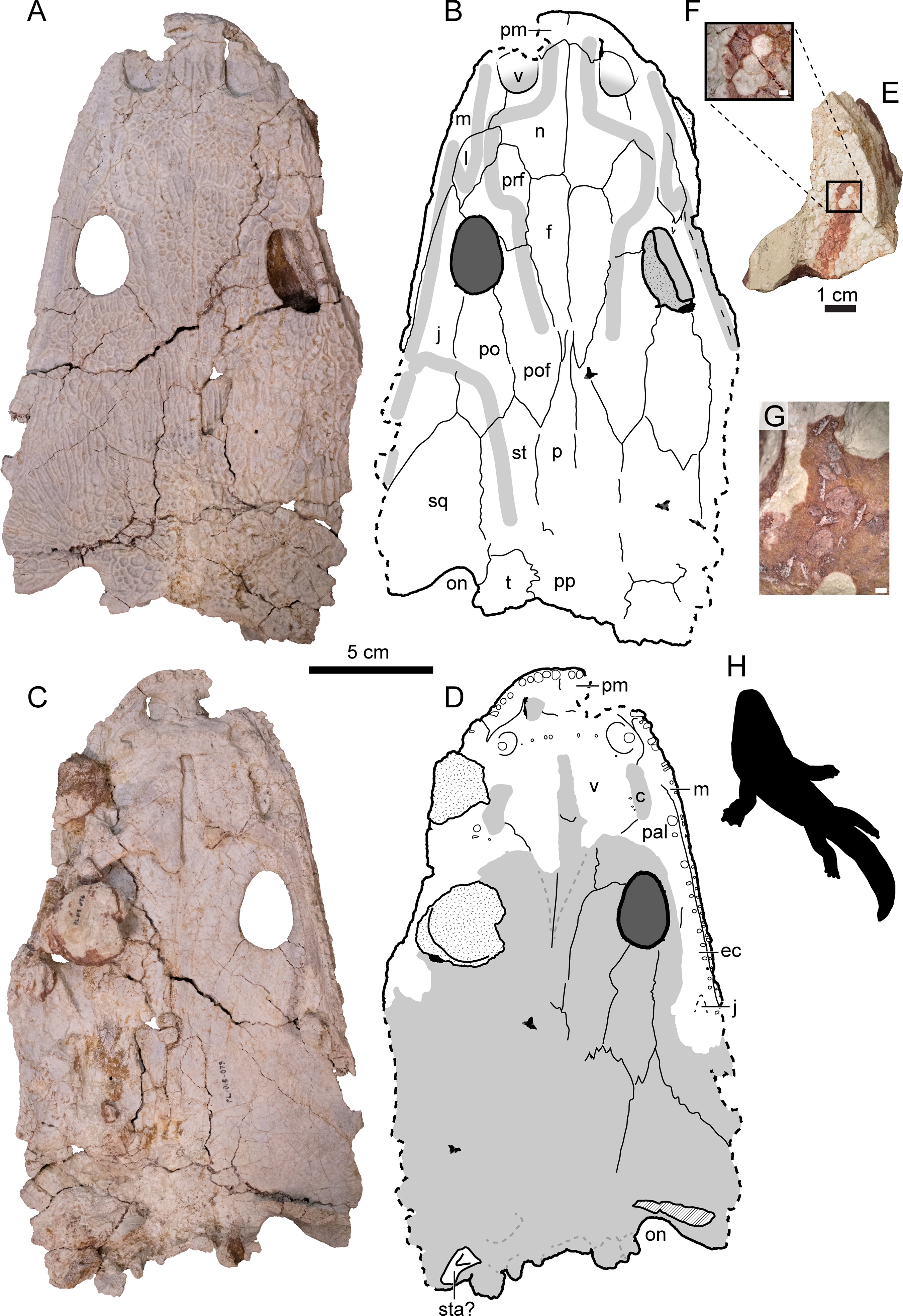

The animals' fossilized remains, uncovered across four excavations between 2014 and 2019, have been relatively undisturbed since then and feature preserved delicate small bones and parts of the creatures' overall skeletal structure. The well-preserved findings could provide insight into how these Triassic amphibians lived and grew up, researchers reported in a new study published Wednesday (April 2) in the journal PLOS One.

Study first author Aaron Kufner, a geologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and colleagues uncovered fossils of Buettnererpeton bakeri in a Wyoming fossil bed called Nobby Knob. These alligator-size creatures belong to an ancient amphibian group known as metoposaurids, a family of large, primitive four-legged amphibians. B. bakeri is the oldest known North American metoposaurid. It lived during the Triassic period (252 million to 201 million years ago) and may have frequented freshwater lakes and rivers as breeding grounds.

It's fairly common to find large piles of bones, known as bone beds, in the fossil record. Typically, bone beds occur when flowing water deposits bones in the same place over many years. Other times, bone beds happen when a group of animals die at the same time and place — which appears to be the case at Nobby Knob.

"This assemblage is a snapshot of a single population rather than an accumulation over time," Kufner said in a statement. The discovery "more than doubles the number of known Buettnererpeton bakeri individuals." Alongside the B. bakeri fossils, the team also found fossilized plants, bivalves and fossilized poop, called coprolites.

The amphibian bones didn't show any signs of having been moved by flowing water, suggesting these creatures came to rest in or near calm waters and were slowly buried by fine sediments during repeated floods. This left some of the fossils in the same shape and arrangement as the animals' actual skeletons. The researchers found B. bakeri fossils of various sizes, which could help explain how the animals grew and aged.

Because the closely grouped bones weren't carried to the site by currents, the researchers suspect the animals perished around the same time. They may have been part of a breeding colony or died because they were somehow prevented from leaving a drying body of water they needed to survive, the team suggested. It's still unclear whether mass metoposaurid die-offs like the one at Nobby Knob were common during the Triassic or whether the site represents an isolated event.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The B. bakeri fossils could help scientists date other metoposaurid fossils, the researchers wrote in the study. The Buettnererpeton fossils were buried deeper than fossils of Anaschisma browni, another metoposaurid, in the Popo Agie Formation — a Triassic formation that spans parts of Wyoming, Colorado and Utah. The finding that the Buettnererpeton fossils were likely older than Anaschisma correlates with other fossil beds that preserve both species and help date the regions and depths at which those fossils were found.

The Nobby Knob bone bed "preserves a wide size range of individuals from a single site that can provide insight into the [development] of metoposaurids," the scientists wrote in the study.

Skyler Ware is a freelance science journalist covering chemistry, biology, paleontology and Earth science. She was a 2023 AAAS Mass Media Science and Engineering Fellow at Science News. Her work has also appeared in Science News Explores, ZME Science and Chembites, among others. Skyler has a Ph.D. in chemistry from Caltech.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.