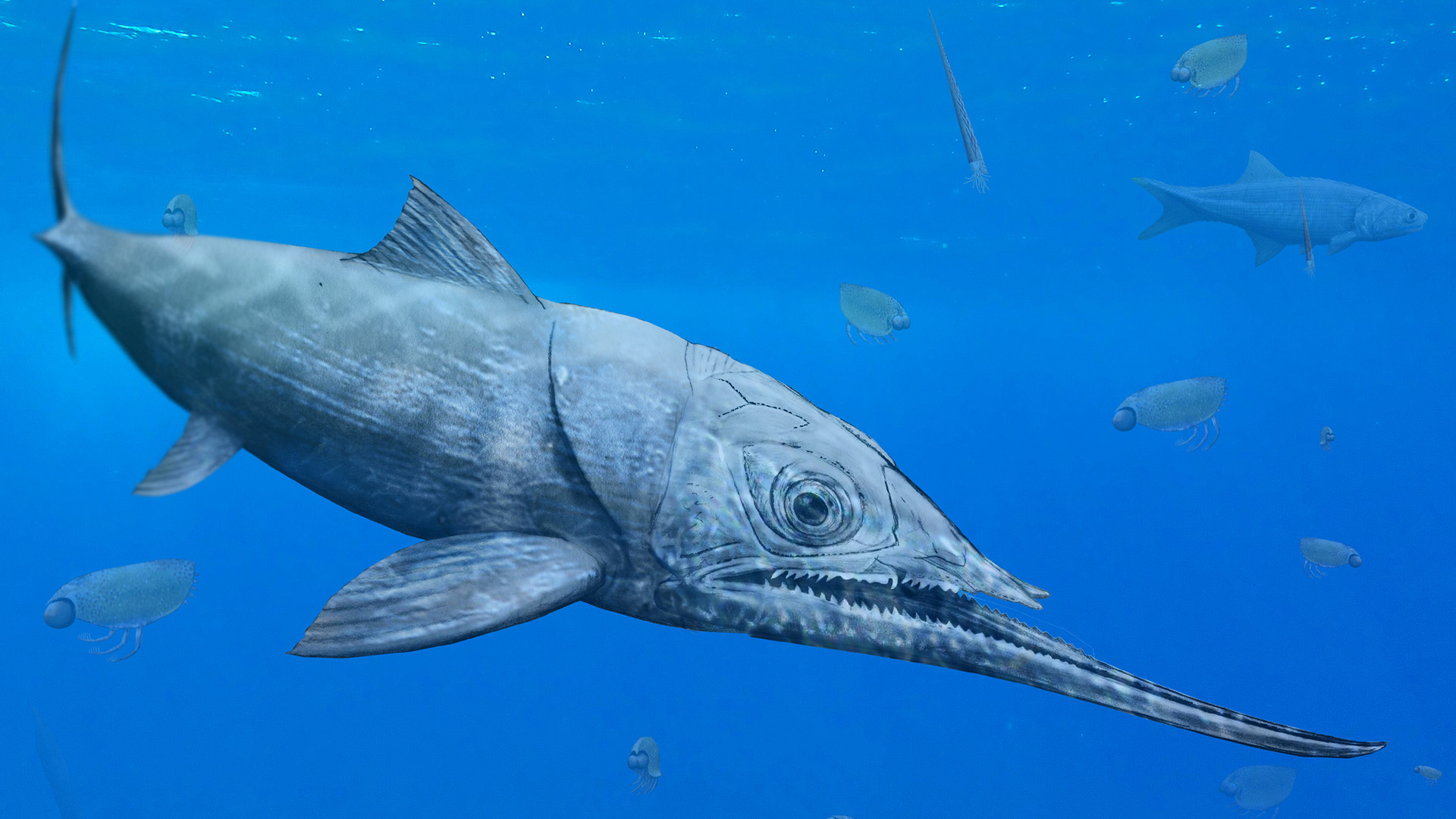

365 million-year-old 'alien' fish had one of the most extreme underbites on record

Scientists think the toothy fish may have used its mismatched jaw to trap prey.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists recently discovered that an ancient fossilized fish may be one of the top contenders for nature's most extreme underbite.

When a researcher first unearthed the first known fossil of this fish in Poland in 1957, he thought it had a long set of fin spines, leading to the alien-inspired name Alienacanthus. But the new analysis reveals that these "spines" were actually an immensely elongated lower jaw studded with teeth, giving this species the oldest — and one of the longest — underbites ever recorded, according to the study, which was published Wednesday (Jan. 31) in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

"The new Alienacanthus finds set the record straight about what this animal actually looks like, as in it doesn't have a weird fin spine but a rather unique lower jaw," lead study author Melina Jobbins, a paleontologist at the University of Zürich in Switzerland, told Live Science in an email.

Article continues belowRelated: Giant ancient fish that likely preyed on humans' ancestors unearthed in South Africa

Alienacanthus lived during the Devonian period (419 million to 358.9 million years ago), when Earth's land was separated into two supercontinents. Since the initial discovery of Alienacanthus, several fossil specimens have been found in the mountains of what is now central Poland and Morocco, which were situated on the northeastern and the southern coasts, respectively, when these ancient fish existed. The presence of the same species on both ends of this supercontinent suggests that Alienacanthus migrated across the ocean, despite sea level fluctuation, the new study's authors wrote in The Conversation.

To learn more about the oddball fish, researchers looked at two nearly complete skulls discovered in the Anti-Atlas mountain range of Morocco. They soon realized that the long protrusion jutting from the head of Alienacanthus was a lower jaw — and it was twice the size of the individual's skull.

Alienacanthus is a placoderm, a group of armored fish that includes some of the first jawed vertebrates. But unlike its placoderm brethren, Alienacanthus' upper jaws could move a tad independently of the skull, which helped to accommodate its lengthy lower jaw, the team wrote in The Conversation. "This animal is so unique that the entire jaw mechanism had to work a little differently to accommodate for the lower jaws," Jobbins told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers compared Alienacanthus to modern-day species with mismatched jaws, such as swordfish, to formulate three main hypotheses for how these fish may have capitalized on their underbite: to trap living prey, to confuse or injure prey, or to sieve through sediments in the ocean basin.

"The most compelling to us is the first hypothesis, trapping live prey, which is based on the teeth," Jobbins said. "The teeth pointing to the back prevent the prey from escaping the mouth once trapped."

The top competitor for the title of "world's worst underbite" is the modern-day halfbeak (Hemiramphidae), a family of tiny fishes with long, beak-like jaws found in warm oceans and some estuaries around the world.

The Late Devonian period presented "literally jaw-dropping diversity in jaw forms and proportions evolved," study senior author Christian Klug, an adjunct professor of paleontology at the University of Zürich, told Live Science in an email. This included the huge, rod-like jaws of the filter-feeder Titanichthys, he added.

Now that this "fin spine" mishap has been cleared up, the researchers are studying Alienacanthus to better understand its jaw mechanics and how the rest of its body looked.

Kiley Price is a former Live Science staff writer based in New York City. Her work has appeared in National Geographic, Slate, Mongabay and more. She holds a bachelor's degree from Wake Forest University, where she studied biology and journalism, and has a master's degree from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus