Alligator gar: The 'living fossil' that has barely evolved for 100 million years

This "living fossil" can grow as large as an alligator, has two rows of needle-sharp teeth, and such strong armor that it survived predatory dinosaurs.

Name: Alligator gar (Atractosteus spatula)

Where it lives: Rivers, reservoirs and coastal bays in southwestern U.S. states, down to Veracruz, Mexico

What it eats: Crabs, fish, birds, mammals, turtles, and carrion

Why it's awesome: With their long snout, thick armored scales, and two rows of piercing teeth, these huge fish could easily be mistaken for a ferocious gator — hence their common name: alligator gar.

They are the largest known species of gar and can grow to around 8 feet (2.4 meters).

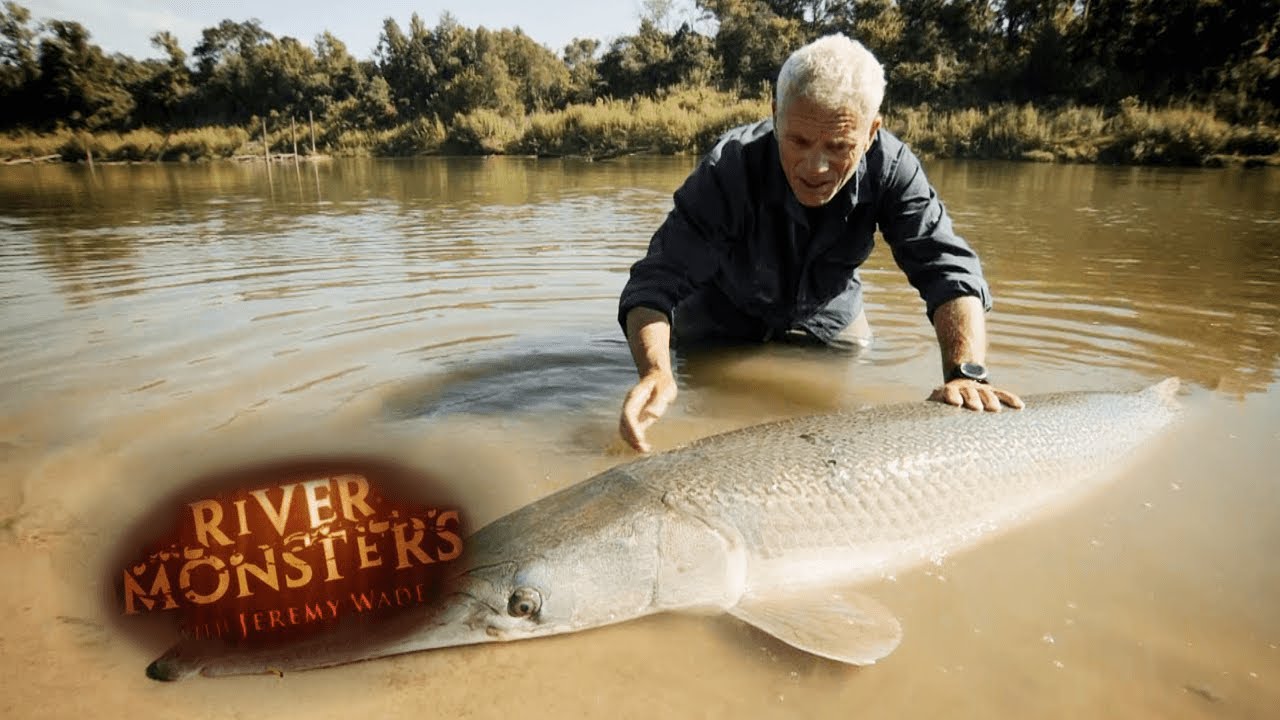

This enormous fish is "a truly prehistoric monster," said biologist Jeremy Wade on "River Monsters." Fossils have shown that these ancient animals existed 100 million years ago during the Cretaceous period (145 million to 66 million years ago), when dinosaurs roamed Earth.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Their survival is in part because of their unique defense system — scales made of a super hard enamel called ganoine," said Wade. "This armor plating has seen them survive predatory dinosaurs." These hard, interlocking flexible scales protect them from threats. Once gars are more than a meter long, their only predator is the alligator.

And alligator gars grow fast. They start as tiny toxic eggs but reach up to 2 feet (0.6 m) long in their first year. They keep growing their entire lives, and can live to 100 years old, Solomon David, an aquatic ecologist at the University of Minnesota, previously told Live Science.

Alligator gars are also among the ultimate "living fossils" — species that have barely changed for millions of years. A 2024 study found gars have the slowest rates of evolution of all jawed vertebrates. They have evolved so slowly that alligator gars and longnose gars (Lepisosteus osseus) — two species separated by 100 million years of evolution — can still produce fertile hybrid offspring. Evolution across such a long period of time typically produces wildly divergent species that could never reproduce.

By contrast, that's about the same amount of evolutionary time that separates wombats and people, two wildly different species that could never reproduce, study author Chase Brownstein, a first year graduate student at Yale, previously told Live Science.

Although their needle-sharp teeth are capable of causing a nasty bite, these ambush predators prefer eating crabs, fish, and birds. Yet, in the 1930s, the Texas Game Fish Commission created a "gar destroyer" to try to electrocute the fish by shooting 200-volts into the water. Today, the fish is protected in Florida and fishing caps are in place in Texas.

Melissa Hobson is a freelance writer who specializes in marine science, conservation and sustainability, and particularly loves writing about the bizarre behaviors of marine creatures. Melissa has worked for several marine conservation organizations where she soaked up their knowledge and passion for protecting the ocean. A certified Rescue Diver, she gets her scuba fix wherever possible but is too much of a wimp to dive in the UK these days so tends to stick to tropical waters. Her writing has also appeared in National Geographic, the Guardian, the Sunday Times, New Scientist, VICE and more.