Fish in the Mariana Trench all have the same, unique mutations

Deep-sea fish adapt to some of the most extreme conditions on Earth. New research analyzing their evolution finds the same mutation across fish species that have evolved on separate timelines — alongside human-made pollutants contaminating the deep sea.

Fish that survive in extreme deep-sea environments have developed the same genetic mutation despite evolving separately and at different times, researchers say.

The scientists also found industrial chemicals in fish and in the ground in the Mariana Trench, meaning human-made pollutants can reach some of the deepest environments on Earth.

Deep-sea fish have developed unique adaptations to survive extreme pressure, low temperatures and almost complete darkness. These species adapt to extreme conditions through unique skeletal structures, altered circadian rhythms and either vision that's extremely fine-tuned for low light, or are reliant on non-visual senses.

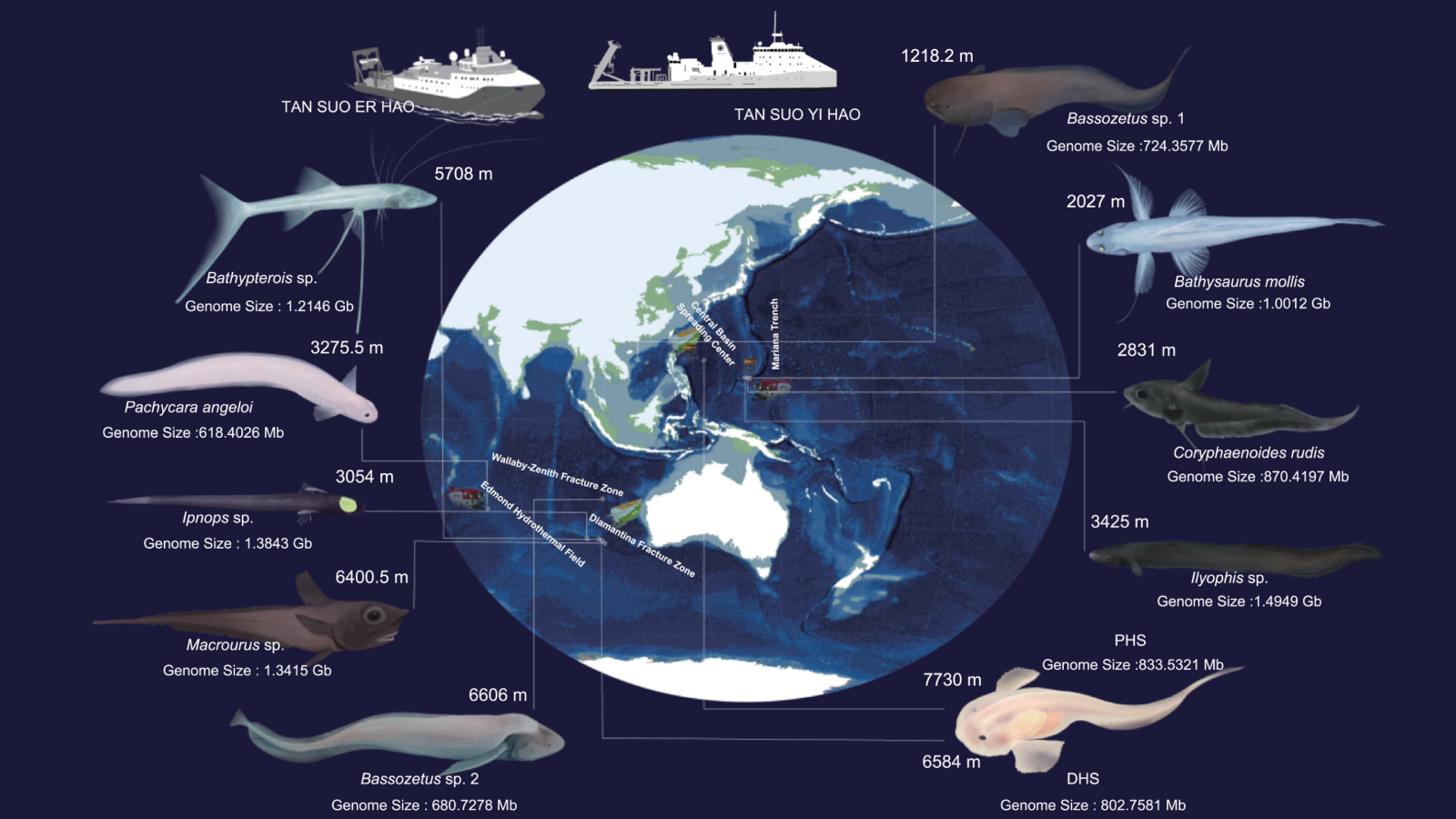

In a new study, published March 6 in the journal Cell, researchers analyzed the DNA of 11 fishes, including snailfish, cusk-eels and lizardfish that live in the hadal zone — the region about 19,700 feet (6,000 meters) deep and below — to better understand how they evolved under such extreme conditions.

The researchers used crewed submarines and remotely operated vehicles to collect samples from about 3,900 to 25,300 feet (1,200 to 7,700 m) below the water's surface, in the Mariana Trench in the Pacific and other trenches in the Indian Ocean.

Tracing the evolution of deep-sea fishes, the researchers' analysis revealed that the eight lineages of fish species studied entered the deep-sea environment at different times: The earliest likely entered the deep sea in the early Cretaceous period (about 145 million years ago), while others reached it during the Paleogene (66 million to 23 million years ago), and some species as recently as the Neogene period (23 million to 2.6 million years ago).

Despite different timelines for making the deep sea their home, all the fishes studied living below 9,800 feet (3,000 m) showed the same type of mutation in the Rtf1 gene, which controls how DNA is coded and expressed. This mutation occurred at least nine times across deep-sea fish lineages below 9,800 feet, study author Kun Wang, an ecologist at Northwestern Polytechnical University, told Live Science in an email.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This means all these fishes developed the same mutation separately, as a result of the same deep-sea environment, rather than as the result of a shared evolutionary ancestor — showing just how strongly deep-sea conditions shape these species' biology.

Related: How deep is the Mariana Trench?

"This study shows that deep-sea fishes, despite originating from very different branches of the fish tree of life, have evolved similar genetic adaptations to survive the harsh environment of the deep ocean — cold, dark, and high-pressure," Ricardo Betancur, an ichthyologist at the University of California San Diego who was not involved in the new study, told Live Science in an email.

It's an example of convergent evolution, where unrelated species independently evolve similar traits in response to similar conditions. "It's a powerful reminder that evolution often reuses the same limited set of solutions when faced with similar challenges — in this case, adapting to the extreme conditions of the deep sea," Betancur said.

The expeditions also revealed human-made pollutants in the Mariana Trench and Philippine Trench. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) — harmful chemicals used in electrical equipment and appliances until they were banned in the 1970s — contaminated the liver tissues of hadal snailfish, the scientists discovered.

High concentrations of PCBs and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), flame retardant chemicals used in consumer products until they fell out of popularity in the early 2000s, were also found in sediment cores extracted from more than 32,800 feet (10,000 m) deep in the Mariana Trench.

Previous research has also found chemical pollutants in the Mariana Trench, as well as microplastics in the deep sea. The new findings further reveal the impacts of human activity even in this ecosystem that's so far removed from human life.

Mariana Trench quiz: How deep is your knowledge?

Olivia Ferrari is a New York City-based freelance journalist with a background in research and science communication. Olivia has lived and worked in the U.K., Costa Rica, Panama and Colombia. Her writing focuses on wildlife, environmental justice, climate change, and social science.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.