Why are cave-dwelling eels growing skin over their left eyes? It may be evolution in action.

These "greedy" eels likely retreated into the gloomy depths of underwater caves in search of tasty crustaceans and are adapting to the darkness by going blind, one eye at a time.

Moray eels that lurk in gloomy, underwater caves appear to be adjusting to the darkness by growing skin over their eyes.

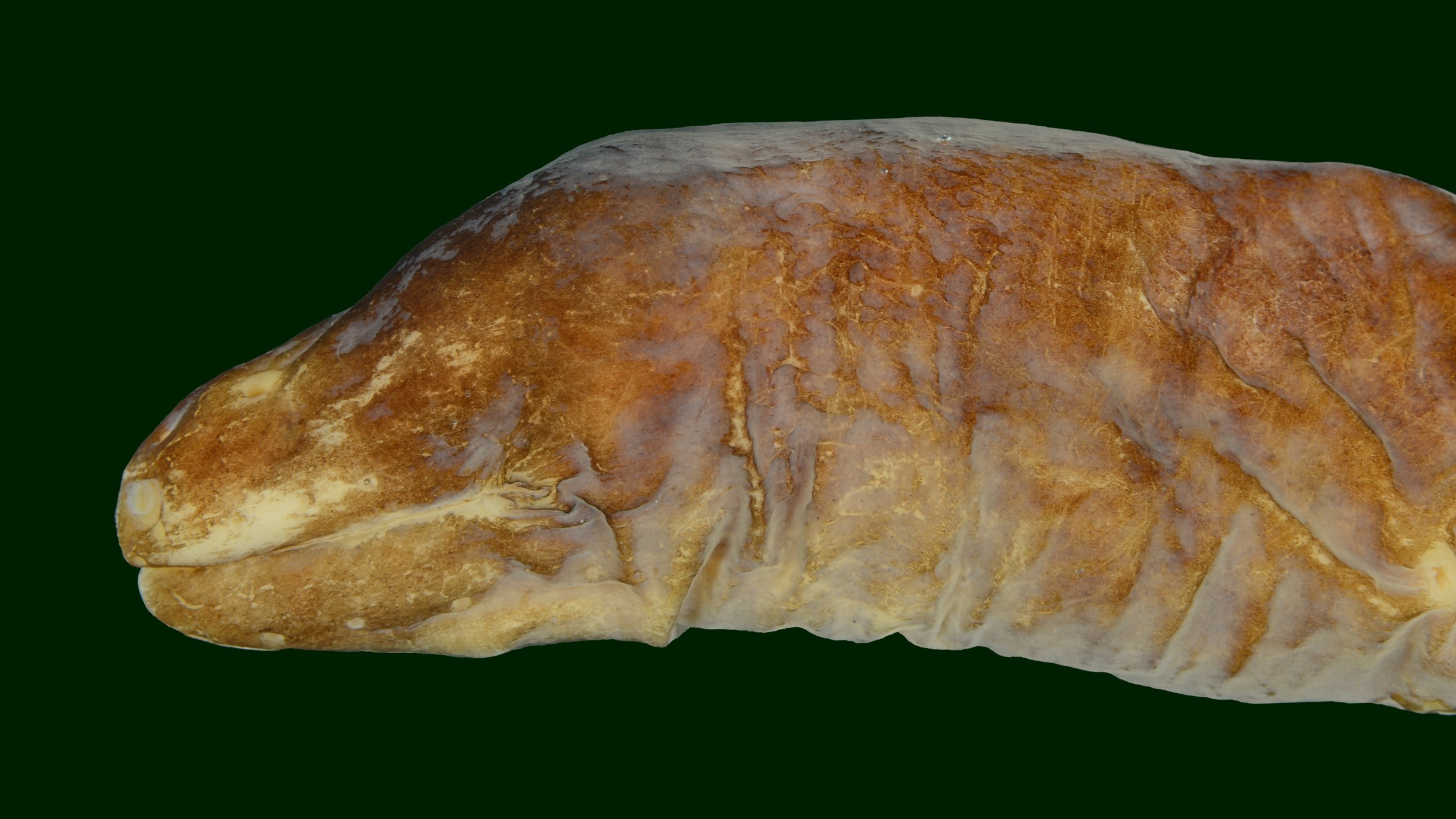

The newly described bean-eyed snake moray (Uropterygius cyamommatus) is the first moray eel species known to inhabit anchialine caves — caves carved into volcanic or limestone rock that are connected to the ocean and whose water levels fluctuate with the tides. During expeditions to Christmas Island, Australia, and Panglao Island in the Philippines, scientists found two specimens that had no visible left eyes, suggesting that the eels may be adapting to their gloomy environment by going blind, one eye at a time.

"Only two specimens from Christmas Island have reduced left eyes and we are not able to know if it is natural or if they just damaged their eyes after being born," said Wen-Chien Huang, a doctoral student of marine biotechnology at the National Sun Yat-sen University in Taiwan and the lead author of a study published March 29 in the journal Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. "But the proportions of their eyes is the smallest that we have ever seen in moray eels, so we speculate it might be the result of adaptation to the aphotic or low-light environment," Huang told Live Science in an email.

Cave explorers first trapped bean-eyed snake morays on Panglao Island in 2001, and several specimens are housed in the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum in Singapore, Huang said. But until now, nobody had recognized them as their own species. A 2014 study in the Raffles Bulletin of Zoology incorrectly listed a bean-eyed snake moray that researchers had caught on Christmas Island as Echidna unicolor, a fish known as the unicolor or pale moray.

The two species are both a uniform brown color, but as its name suggests, the bean-eyed snake moray has "tiny bean-shaped eyes" and a longer tail with more vertebrae than the pale moray, the researchers wrote in the new study. Whereas pale morays have been found in coral reefs in the Pacific and Indian oceans, bean-eyed snake morays have only been spotted in a handful of caves on Christmas and Panglao islands.

Related: Does evolution ever go backward?

Researchers caught the most recent specimens more than 10 years ago with baited traps and pickled them in alcohol to preserve them. It's unclear why or when bean-eyed snake morays retreated into the gloomy cave depths, but the authors of the new study suspect it could be linked to their voracious appetites. "I think one of the reasons they went to inhabit caves is the food source, since there are abundant crustaceans inside the caves," Huang said. The scientists who caught them reported that the "greedy" eels hungrily devoured the bait they used to lure them.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For the new study, Huang and his colleagues analyzed nine specimens collected between 2001 and 2011. Two of them had "a reduced left eye embedded in skin," with no apparent change in the underlying bone structure. The researchers think they may have captured evolution in action and that, in the absence of light, skin encroaching on the eels' eyes could save them the high energetic cost associated with eyesight.

It is not unusual for cave-dwelling fish to go entirely blind, and many of the nearly 300 fish species that live in caves have done so. A species closely related to the bean-eyed snake moray, the few-vertebrae moray (U. oligospondylus), has similarly reduced eyes and lurks in the shadows between wave-crashed boulders, where it relies on its sense of smell to detect prey.

Scientists are still unsure exactly why skin is growing over the eels' eyes and whether this potential adaptation to their cave habitat is spreading among the population. Due to the low number of preserved specimens, researchers haven't performed genetic and other molecular testing to answer these questions, Huang said. "These are issues that we are interested in, but can only be resolved when more fresh specimens are available."

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.