Cicada double brood event: What to expect as trillions of bugs emerge in Eastern US

When and where will the double cicada brood emerge? Here's what to expect from this rare phenomenon, which occurs only once every 221 years.

For the first time in 221 years, two gigantic broods of periodical cicadas are emerging from the ground simultaneously in the U.S. ready to engage in a raucous mating frenzy.

The rare double cicada brood includes the two of the largest cicada broods, Brood XIII and XIX, which will co-emerge en mass after having lived underground for 17 and 13 years, respectively.

Periodical broods are found only in eastern North America. When they finally emerge after a long juvenile period, they do so in enormous numbers. Once hatched, the immature periodical cicadas, known as nymphs, live off tree root sap underground before emerging in adulthood to mate — a noisy and frantic display that takes place over several weeks.

This incredibly rare wildlife spectacle last occurred in 1803, when Thomas Jefferson was president, and it won't happen again until 2245.

Although there are more than 3,000 cicada species, just seven are periodical cicadas (Magicicada). Of these, three have 17-year life cycles, and four have 13-year life cycles. Periodical cicadas have much longer life cycles than nonperiodical cicadas, which mature each summer and are found globally.

When will the cicadas start emerging?

Scientists at the University of Connecticut (UConn) have mapped cicada brood activity in the Periodical Cicada Project database, which shows that the double brood will begin emerging in late April 2024 and continue for several weeks.

The first cicadas emerged around April 25, with sightings in Illinois, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Kansas and Missouri, according to the Cicada Safari app, which tracks the event.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The emergence will last for around a month and a half, according to Indiana's Purdue University, so by mid-June the billions of bugs now surfacing will be gone.

On May 29, Google Doodle celebrated the emergence with a band of bugs playing instruments. "As the cicada shells pile up on trees and sidewalks and the buzzing fills your ears, try not to let them bug you," Google Doodle representatives said in a statement. "These clumsy insects fly by the trillions but don't sting, bite, or poison. Plus, many predictions show they'll be out of your hair by late June, leaving behind a feast for local animals like birds and raccoons."

How many cicadas could emerge at the same time?

"Billions, even trillions, of cicadas are going to emerge at the same time across 17 states," Chris Simon, a professor in UConn's Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and one of the scientists who runs the database, told Live Science.

Despite the huge volumes of insects set to emerge, the co-emergence of Brood XIII and XIX likely won't look much different from other periodical cicada emergences. That's because, for the most part, they won't emerge from the same locations. There's only a small woodland area in Springfield, Illinois, where the two broods may co-emerge.

"The broods won't overlap significantly due to the latitudinal spread involved," John Cooley, founder of the Periodical Cicada Project and a professor in UConn's Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, told Live Science. "But there will be a lot of cicadas … just as there are a lot of ants, flies. Insects come in large numbers."

Blue-eyed mutant cicadas

Most of the billions of cicadas emerging have blood-red eyes. But a handful — around one-in-a-million — have blue eyes due to a rare mutation. Two of these blue-eyed bugs were recently found outside of Chicago, with 4-year-old Jack Bailey from Wheaton, Illinois, finding one in his yard, while another was spotted in the Orland Grassland forest preserve.

Jack and his mother Greta Bailey sent the rare cicada to the Field Museum for analysis. "I have been in Chicago for five periodical cicada emergences of our Brood XIII, and this is the first blue-eyed cicada I have seen," Jim Louderman, a collections assistant in the insect division of the Field Museum, said in a statement.

"I have also seen two emergences of Brood X in Indiana and two emergences of Brood XIX in Central Illinois," he added. "These rare [blue-eyed] insect emergences are always infertile and can not have offspring, which is why they remain so rare."

Why is this event so rare?

It is a rare occurrence for two specific periodical broods of different life cycles to emerge at the same time and overlap in location.

"The co-emergence of any two broods of different cycles is rare, because the cycles are both prime numbers,” Cooley said. "Any given 13- and 17-year broods will only co-emerge once every 13 x 17 = 221 years."

Despite their geographic proximity, the two broods have not emerged at the same time for 221 years, although many other 13-year and 17-year broods have appeared in the same year.

"2015 was the last time a 13-year brood emerged with a 17-year brood, when Brood XXIII emerged with Brood IV. However, the two broods weren't geographically close," Simon told Live Science. "Similarly, adjacent Brood IV and Brood XIX both appeared in 1998 but, again, weren't close."

What areas will be affected?

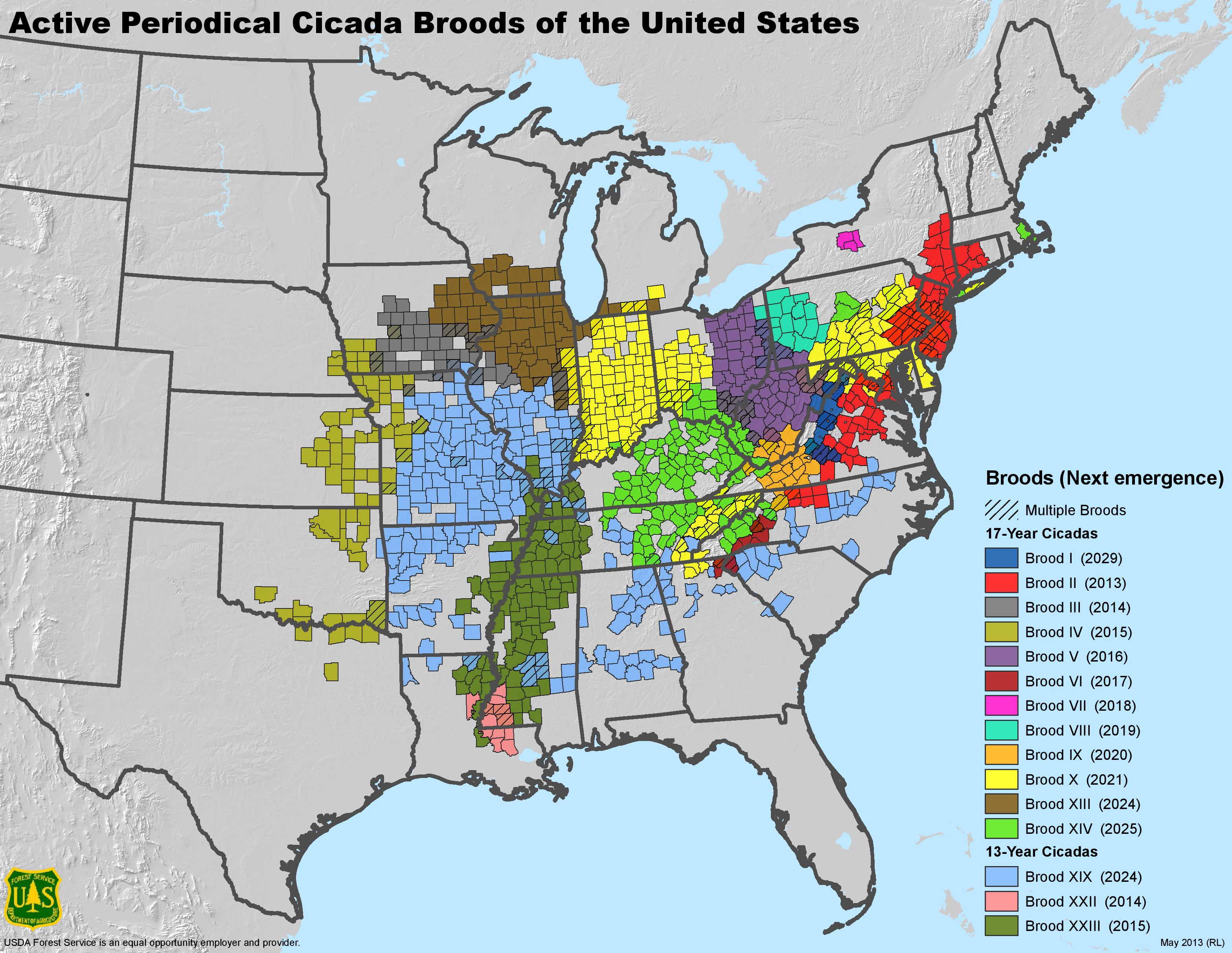

According to the scientists who are tracking the broods, the Periodical Cicada emergence map offers the best guess of where they will appear. Brood XIII is expected to emerge in the Midwest, mostly around north-central Illinois, Ohio and Iowa. Brood XIX will cover parts of Illinois, as well as a wider geographic area in the southeastern U.S., including Louisiana, Virginia and North Carolina.

What will happen if they interbreed? Will an entirely new brood be created, with a new cycle?

The two broods are not likely to interbreed as there is limited overlap between them. "There will not be a new brood or cycle,," Simon said. And even if the two broods do interbreed, scientists don't expect much to happen. "Even if the broods were to interbreed, any offspring would be indistinguishable from cicadas that were not hybrids," Simon said.

Working with scientists from Kyoto University and Shizuoka University in Japan, UConn researchers found evidence of extensive interbreeding between 13 and 17-year cicadas of the same lineage (excluding Magicicada tredecim), but they didn't note any change between the life cycles. There are four genetic lineages of periodical cicadas in the genus Magicicada: M. decula, M. cassini, M. decim and M. tredecim.

"Scientists in the past have speculated that mating between 13-year and 17-year periodical cicadas would not create an intermediate life cycle (e.g., 15-year); instead, the offspring would be either 13-year or 17-year, but not both," Simon said. "We still only see either 13 or 17-year cicadas in nature. Whether one life cycle is dominant to another is unknown. And, importantly, there are very few places where 13-year and 17-year cicadas currently overlap."

What can people expect to see?

The double brood is expected to look like a normal periodical cicada emergence, with huge numbers of cicadas emerging from the ground in the evening. In the first week of the emergence, cicadas will be seen in the mornings, sitting on lower vegetation after shedding their exoskeleton shell, before climbing upward into trees to mate and, eventually, for females to lay eggs. A fresh batch of cicadas will appear the next morning until all of the cicadas have emerged.

After climbing high into trees, the males will emit a loud shrieking mating noise, using powerful drum-like organs known as tymbals to attract females. The females will then return the call in a chorus of clicks that increase in intensity and volume as mating gets underway.

"It will look like a pretty normal periodical cicada year with lots of active, flying adults for about three weeks, depending on how the spring goes, as the adults complete their mating and egg laying activities," Cooley said. "Then the adults will die, and things will go back to normal. About six weeks later, the eggs will hatch, but most people won't notice that, since the hatchlings are tiny and inconspicuous."

What will happen to the cicadas after they emerge?

Most of the cicadas will die within two to six weeks after reproducing, with many dying in the crush of emergence. After three weeks, most of the cicadas will be high in the trees, and after a month, there will be large numbers of female cicadas laying eggs in trees. The eggs will then fall to lower ground to hatch and burrow underground.

"Emerging isn't without risk, as many of the cicadas will be eaten by predators, while others may be killed by later cicadas walking on them while their outer casing is still soft,"Simon said. "Some will survive to move into the higher vegetation and mate and lay eggs."

Do cicadas bite?

Cicadas are mostly harmless to humans. They aren't poisonous and don't bite or sting, as they lack the physical structures required to do so, according to Purdue University. "Their mouth parts are… more like a straw than teeth so they can't bite," representatives wrote in a statement. "The worst that most cicadas will do to a person is startle them."

The cicadas could cause problems to pets if consumed — but only if they gobble up enough of the insects. "In most cases, your dog will be fine after eating a few cicadas," Dr. Jerry Klein, chief veterinary officer for the American Kennel Club, said in a statement. "However, dogs that gorge on the large, crunchy insects will find the exoskeleton difficult to digest and can suffer serious consequences."

These include a stomach upset, abdominal pain, vomiting and bloody diarrhea that may require treatment, Klein said.

When will the next dual emergence be, and how will it differ from this one?

The next co-emergence is expected in 2037, but the two broods involved (IX and XIX) will not be adjacent. The next time this will happen with adjacent broods is in 2076, according to the UConn researchers.

You can contribute to the periodical-cicada research by downloading the free Cicada Safari app to report local cicada sightings.

Carys Matthews is a freelance writer for Live Science and has a passion for the natural world. Most recently the group digital editor of BBC Wildlife and BBC Countryfile Magazine, she writes about the outdoors, nature and health and fitness. Prior to this she has worked for a number of sports and environmental titles in the U.K.