Kamikaze termites blow themselves up with 'explosive' backpacks — and scientists just figured out how

Kamikaze termites in French Guiana carry highly volatile toxic "rucksacks" that are ready to be deployed in an instant, when the termite needs to defend its colony.

Kamikaze termites in French Guiana have evolved a unique defense mechanism — carrying "rucksacks" filled with a toxic liquid that they can trigger to explode, poisoning their enemies in the process. Now, scientists have solved the mystery of how these deadly backpacks can be safely carried around then detonated on demand.

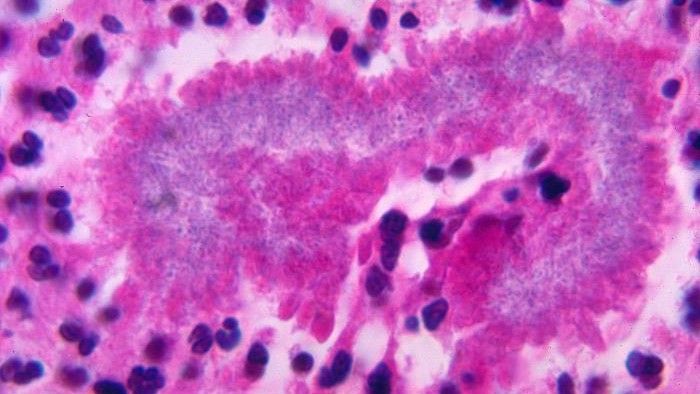

In 2012, researchers discovered that older Neocapritermes taracua worker termites are armed with blue spotted backpacks that explode when they are threatened.

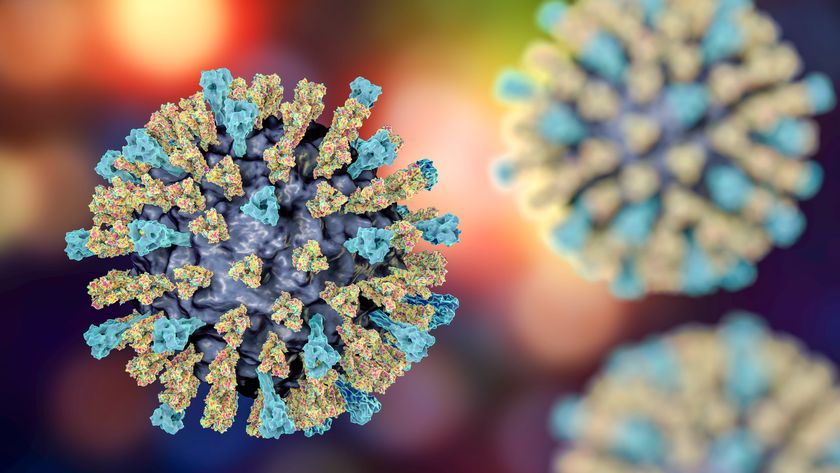

The N. taracua workers have a specialized pair of glands in their abdomens that gradually secrete the enzyme blue laccase BP76 into pockets on their backs. As they age, the termites accumulate "rucksacks" filled with these blue, copper-containing blue crystals.

When faced with a threat, the aging workers rupture their bodies, mixing the enzyme with relatively benign secretions produced in their salivary glands. The result is a sticky liquid, rich in highly poisonous benzoquinones that can immobilize or kill predators.

However, researchers were puzzled by how BP76 could remain in a solid state stored on the termites' backs, while still staying primed for an instant reaction upon rupture.

The new study, published Aug. 15 in the journal Structure, solved the mystery by providing the first high-resolution crystal structure of this enzyme.

"The enzyme's three-dimensional structure reveals that BP76 employs a variety of stabilization strategies," study lead author Jana Škerlová, a researcher at the Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry of the Czech Academy of Sciences, said in a statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The enzyme is tightly folded, much like folding a piece of paper into a compact shape, which helps it resist degradation over time. Another layer of protection comes from sugar molecules that are attached to the protein, forming a protective shield that further stabilizes it.

Related: Scientists discovered the oldest termite mounds on Earth — and they're 34,000 years old

One of the more intriguing features of BP76 is a rare and unusually strong chemical bond between two amino acids, lysine and cysteine, near the enzyme's active site. This bond is not commonly found in enzymes and plays a crucial role in maintaining BP76's structure, especially when the enzyme is stored as a solid on the termite's back, the researchers found.

This bond acts like a special locking mechanism, ensuring that the enzyme retains its shape and remains fully functional, ready to be deployed in an instant when the termite needs to defend its colony.

"Just as knowledge about individual components of an instrument sheds light on how it works, knowing the three-dimensional structure of a molecule helps us understand a biological process," study co-author Pavlína Řezáčová, a structural biologist at the Czech Academy of Sciences, said in the statement.

The ability for termites to stably store and accumulate this enzyme as they age is critical to protect the colony. Previous research theorized that, because the mandibles of termites dull over time, older termites may not be as effective at foraging or maintaining the nest as younger workers.

With their exploding rucksacks, older workers may instead specialize in providing a final, deadly act to defend the colony.

Jacklin Kwan is a freelance journalist based in the United Kingdom who primarily covers science and technology stories. She graduated with a master's degree in physics from the University of Manchester, and received a Gold-Standard NCTJ diploma in Multimedia Journalism in 2021. Jacklin has written for Wired UK, Current Affairs and Science for the People.