'That's a huge amount of movement for a single mammoth': Woolly female's steps retraced based on chemistry of 14,000-year-old tusk

New analysis of a 14,000-year-old woolly mammoth tusk has pieced together the life of a female mammoth that likely died at the hands of hunters close to Alaska's oldest archaeological site.

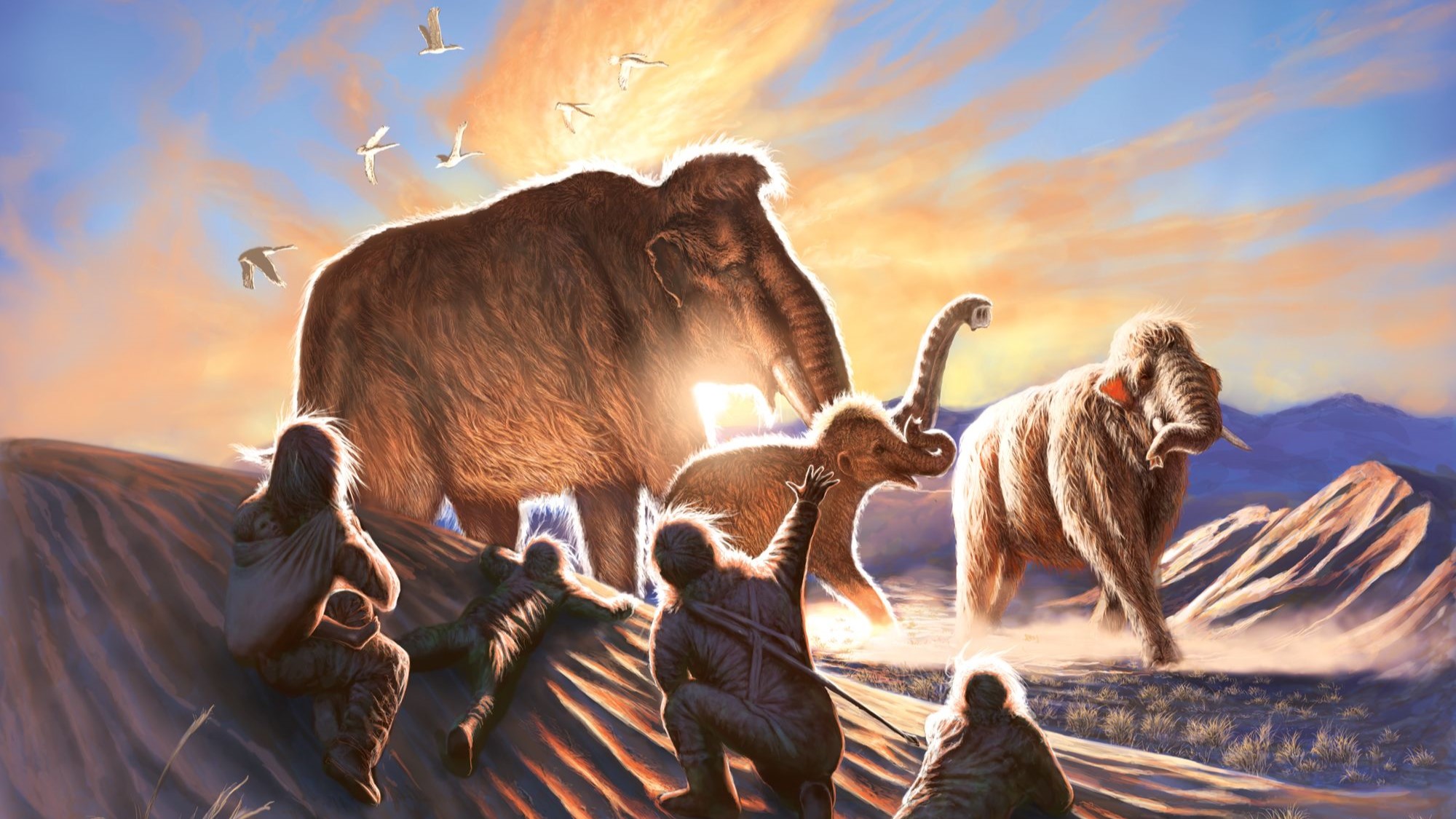

Scientists have retraced the journey of a female woolly mammoth from her birthplace in present-day Canada to eastern central Alaska, where she met her end around 14,000 years ago at the hands of hunter-gatherers.

The mammoth, whose name Élmayuujey'eh translates to "hella lookin" in the aboriginal Kaska language, was likely killed by early Beringian hunter-gatherers when she was 20 years old. Her existence is known thanks to a complete tusk discovered at Swan Point, one of the oldest archaeological sites in the Americas.

Élmayuujey'eh, or Elma for short, was born toward the end of the last ice age in what is now the Canadian province of the Yukon, where she likely stayed for the first decade of her life. A new analysis of the mammoth's tusk suggests she then set off across the frozen landscape, covering roughly 620 miles (1,000 kilometers) in under three years.

"That's a huge amount of movement for a single mammoth," study co-author Hendrik Poinar, a professor of anthropology at McMaster University in Canada and the director of the McMaster Ancient DNA Center, said in a video released by the university. Elma trekked all the way into Alaska and eventually slowed down, Poinar said.

Her remains indicate she was closely related to both a juvenile and a newborn woolly mammoth whose bones were also unearthed at Swan Point. The trio may have belonged to one of two matriarchal herds that roamed an area within 6.2 miles (10 km) of Swan Point, according to the study, published Wednesday (Jan. 17) in the journal Science Advances.

Related: Huge mammoth jaw at least 10,000 years old pulled up from Florida river

To piece Elma's life together, researchers split her tusk lengthwise and examined thin layers of ivory that formed like the rings of a tree trunk throughout her years. The proportion of different versions of chemical elements, or isotopes, in these layers contained valuable information about the mammoth's diet and location, enabling the team to retrace her steps.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers also analyzed ancient DNA in Elma's tusk and compared it with the remains of eight other woolly mammoths found in and around Swan Point, including the two youngsters. Their results revealed the mammoths belonged to at least two distinct herds that may have gathered in the region along with other mammoth herds — a congregation that would have attracted humans.

"Indigenous hunters clearly saw that the mammoths were using this as a really important location for feeding," Poinar said in the video. "The data to me suggest that these were Indigenous people that appreciated, looked at, loved these phenomenal beasts walking on this landscape. But it would make sense too, that in times of need, that you would kill them — a mammoth like that could provide food for a huge number of people over a long period of time."

Elma's remains indicate she was in the prime of early adulthood and well nourished at the time of her death. She likely died in late summer or early autumn, which coincides with when humans would have set up their seasonal hunting camp at Swan Point and suggests she died at the hands of hunters, according to the study.

Very little is known about the geographic movements and behaviors of woolly mammoths — or about how these animals interacted with early Americans — but stories like Elma's can paint us a picture.

"This analysis of lifetime movements can really help with our understanding of how people and mammoths lived in these areas," co-author Tyler Murchie, a postdoctoral researcher and former member of the MacMaster Ancient DNA Center, said in a statement. "We can continue to significantly expand our genetic understanding of the past, and to address more nuanced questions of how mammoths moved, how they were related to one another and how that all connects to ancient people."

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.