Ancient sea monsters grew their long necks super fast after Great Dying by adding more vertebrae

Some of these aquatic reptiles of the dinosaur era had dozens of individual bones running down their long necks.

Millions of years ago, as dinosaur giants were stomping around on land, other giant reptiles were dominating the oceans — and some of them, like plesiosaurs and similar animals, grew extremely long, snake-like necks.

Now, scientists have discovered how some of these early marine reptiles evolved these lengthy necks rather quickly — by adding new vertebrae to their spines.

Researchers in China and the U.K. examined the fossil of a marine reptile called a pachypleurosaur from the early Triassic period (251.9 to 201.3 million years ago), which kicked off the start of the dinosaur era. This newly discovered species, which they named Chusaurus xiangensis, had a neck about half as long as its torso.

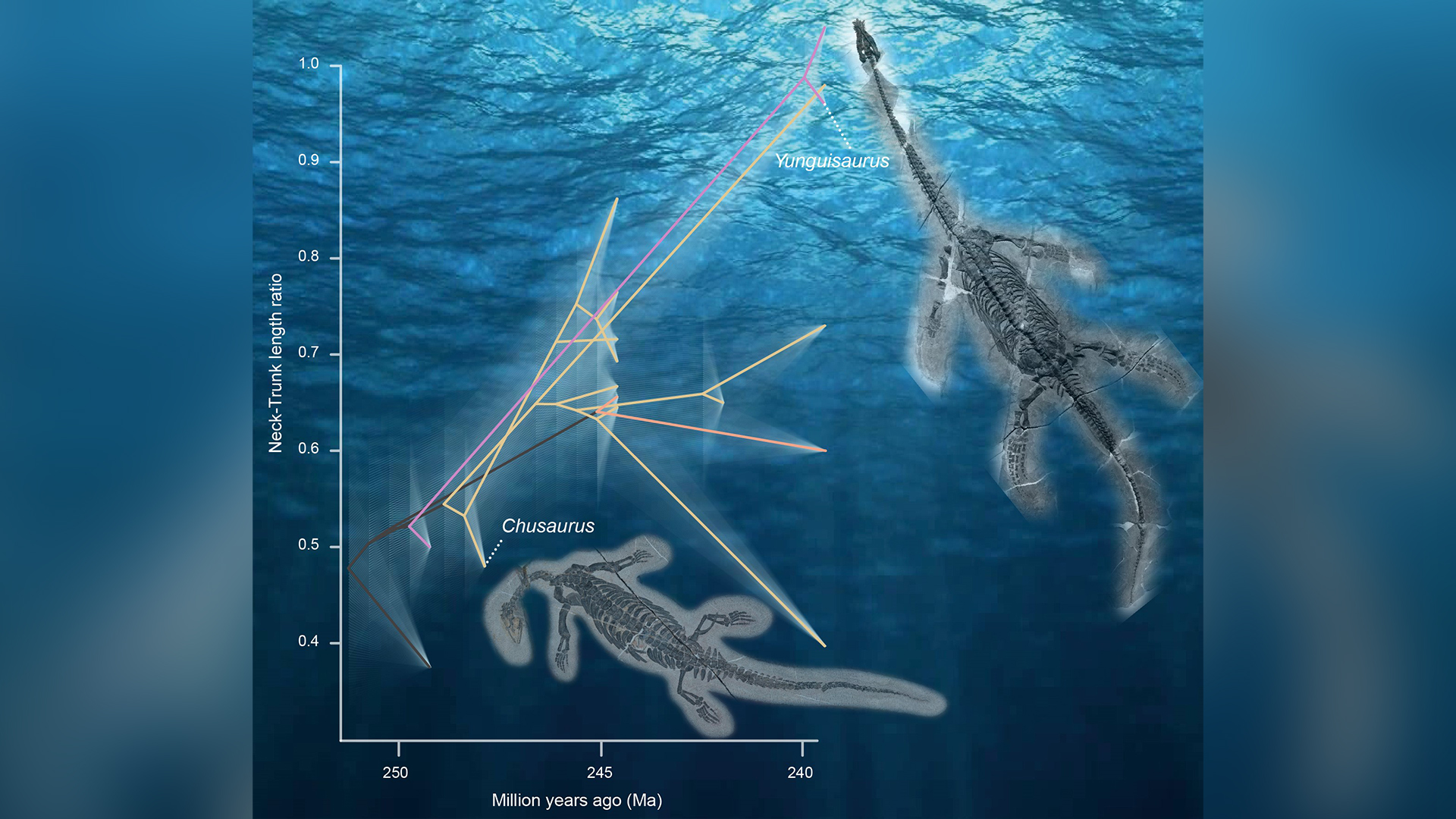

Initially, the researchers were not sure whether C. xiangensis was a pachypleurosaur because its neck seemed too short —some of its relatives from later in the Triassic period sported necks more than 80% the length of their torsos, the authors noted in the study, published on Aug. 31 in the journal BMC Ecology and Evolution. But despite its relatively short neck, the researchers determined that the fossil was indeed, a pachypleurosaur.

To find out how these animals developed super-long necks in super-quick time, the researchers compared fossils of eosauropterygians — the group that includes pachypleurosaurs and other ancient, long-necked marine reptiles — from different periods of the Triassic era.

They found that the ratio of the length of their torsos to necks went from about 40% to 90% within roughly 5 million years.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After that, their necks stopped growing longer quite as quickly. "They had presumably reached some kind of perfect neck length for their mode of life," Benjamin Moon, one of the paper's co-authors and a paleontologist at the University of Bristol in the U.K., said in a statement.

"We think, as small predators, they were probably mainly feeding on shrimps and small fish, so their ability to sneak up on a small shoal, and then hover in the water, darting their head after the fast-swimming prey was a great survival tool."

These early long-necked animals also had fewer vertebrae than some of their later relatives. "Chusaurus already had 17, whereas later pachypleurosaur had 25," Long Cheng, one of the study's co-authors and a paleontologist at the Wuhan Centre of China Geological Survey, said in the statement.

"Some Late Cretaceous plesiosaurs [100 million to 66 million years ago] such as Elasmosaurus even had 72, and its neck was five times the length of its trunk," Cheng added. "With so many vertebrae, these long necks must have been super-snakey and they presumably whipped the neck around to grab fishy prey while keeping the body steady."

This speedy evolution of long necks early in the Triassic period was likely due to the mass extinction — dubbed the Great Dying — that preceded it. "The end-Permian mass extinction had been the biggest mass extinction of all time and only one in twenty species survived," study co-author Michael Benton, also a paleontologist at the University of Bristol, said in the statement. "The Early Triassic was a time of recovery and marine reptiles evolved very fast at that time, most of them predators on the shrimps, fishes and other sea creatures.

"They had originated right after the extinction, so we know their rates of change were extremely rapid in the new world after the crisis."

Ethan Freedman is a science and nature journalist based in New York City, reporting on climate, ecology, the future and the built environment. He went to Tufts University, where he majored in biology and environmental studies, and has a master's degree in science journalism from New York University.