7 rules that explain Earth's most extreme animal shapes and sizes

Nature has a few rules to help explain the extreme shapes and sizes we see in the animal kingdom.

Animals come in extreme shapes and sizes, from enormous elephants and colossal squids to miniature marmoset monkeys and teeny-weeny frogs. But there is some method to nature's madness, and while evolution can be unpredictable, there are a few established rules that govern how animals take these extreme shapes.

Below are seven rules that scientists have established to describe evolutionary trends. Keep in mind that these are general trends, and not every species is covered. Even nature's rules are made to be broken.

Bergmann's rule

Bergmann's rule states that animals evolve to be larger in colder climates. This trend occurs because larger animals have a smaller surface area-to-volume ratio, which helps to reduce heat loss. Thus bigger bodies are better at retaining heat compared to smaller bodies.

A polar bear (Ursus maritimus) in the Arctic, for example, is more than two and a half times taller than a sun bear (Helarctos malayanus) living in the tropics of South East Asia, according to The University of Texas at Austin. The rule is named after the German biologist Carl Bergmann, according to Oxford Reference.

Related: The animal kingdom is full of cheats, and it could be a driving force in evolution

Allen's rule

Allen's rule states that animals in colder climates tend to have comparatively smaller appendages, such as limbs, ears and tails, than their relatives in warmer temperatures. Similar to Bergmann's observation, this rule is all about retaining heat.

Extremities typically have more surface area than volume; thus, larger appendages lose heat faster than smaller ones. For example, Arctic hares (Lepus arcticus) have shorter legs and smaller ears than American desert hares, such as black-tailed jackrabbits (L. californicus) and antelope jackrabbits (L. alleni). Allen's rule is named after American zoologist Joel Allen, according to Memorial University of Newfoundland in Canada.

Square-cube law

The square-cube law is based on the mathematical principle that the ratio of two volumes is greater than the ratio of their surfaces. This principle means that as animals grow larger, their volume increases faster than their surface area, with larger animals eventually gaining more mass than their limbs can support.

The square-cube law imposes a theoretical limit on how big animals can get, Live Science previously reported. Scientists believe the weight limit is around 120 tons (109 metric tons) for land animals.

Island rule

The island rule, also called the island effect or Foster's rule, holds that small animals on islands tend to evolve into giant versions of their mainland relatives, and large animals tend to evolve into dwarf versions of their mainland relatives.

Under the island rule, animals on the extreme ends of the size spectrum move toward an intermediate size that suits the island's resources and predators, or lack thereof. A 2021 study published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution found that the island rule is widespread in mammals, birds and reptiles, with examples including giant lizards and extinct dwarf elephants.

Related: This colossal extinct whale was the heaviest animal to ever live

Island birds evolve toward flightlessness

A 2016 study published in the journal PNAS found that island birds evolve toward a flightless form. From the extinct Mauritius dodos (Raphus cucullatus) to living New Zealand kiwis, flightlessness is a long-established phenomenon on islands. However, most island birds still retain their ability to fly. What the 2016 study established is that even flying birds evolve smaller flight muscles and longer legs on islands, meaning that all island birds evolve at least some way toward flightlessness. These traits are more prominent on islands with few predators, implying that reduced predation pressure encourages birds to give up flight.

Deep-sea gigantism

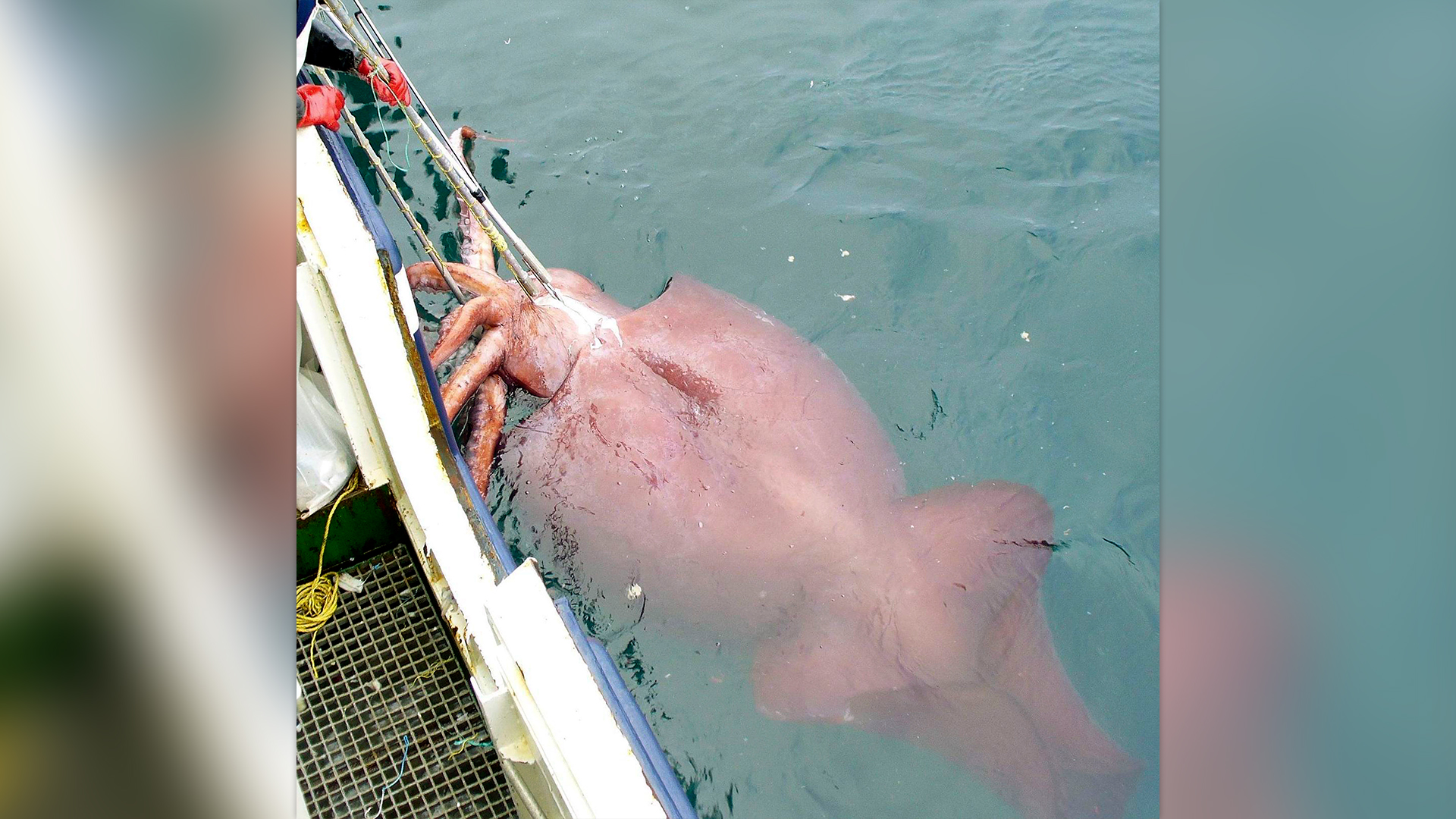

There's a tendency for invertebrate animals to evolve into giants at great ocean depths. Think colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni) or giant crabs. Larger animals can move farther to find food and mate, which may help explain why there are so many giants in the deep sea where resources are scarce, Live Science previously reported. Larger animals also have more efficient metabolisms and a greater capacity to store energy from food. Finally, the deep ocean is cold, so deep-sea gigantism correlates with Bergmann's rule of colder climates producing larger animals.

Rensch's rule

Rensch's rule describes a trend in sexual dimorphism, where one sex is larger than the other. The rule states that there's a pattern within animal lineages of sexual dimorphism decreasing with size when females are larger than males and increasing with size when males are larger than females.

A 2004 study published in the journal PNAS found that in larger species of shorebird, males are typically larger than females, and sexual dimorphism increases the bigger the males of a species get. In contrast, females are typically larger than males in smaller shorebirds.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.