Spooky, subterranean daddy longlegs with ghostly pale bodies discovered

Researchers believe that one of the new species may be a relic from an ancient ecosystem in Australia.

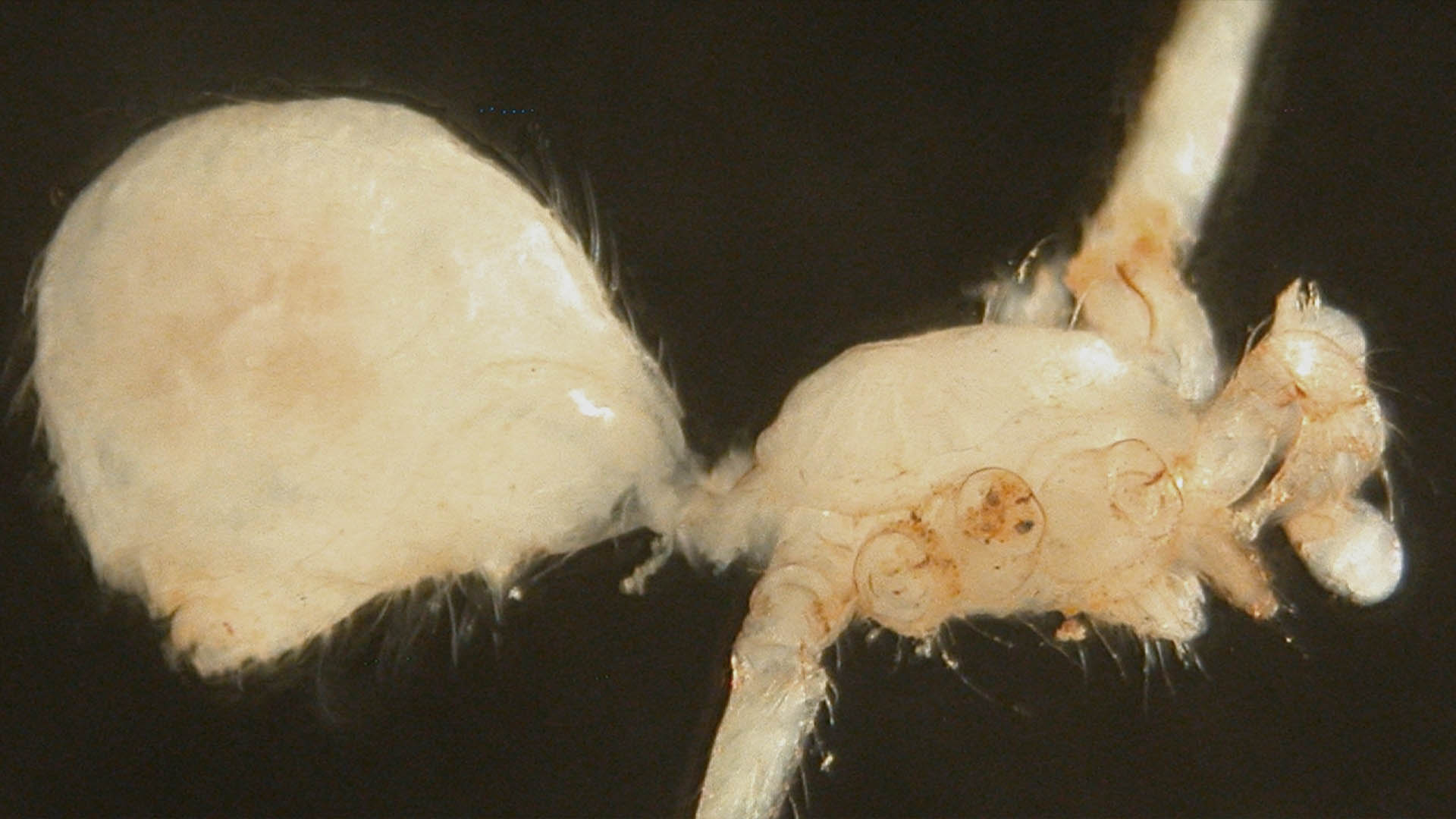

Two new species of blind and colorless daddy longlegs spider have been discovered — one in the dry western region of Australia, and one on the lush tropical island of Réunion.

Both of the species live in underground habitats, which likely led to their colorless bodies and blindness. And researchers believe that both of these subterranean spiders could tell us an interesting story about the way species evolve and move over time.

This study "really highlights why it is that biodiversity discovery matters and how it is that you can find really unusual species in some of the strangest places that you look," Prashant Sharma, a biologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who was not involved in the new research, told Live Science.

Spiders in the Pholcidae family are found all over the world and are notable for their long, spindly legs, which earned them the common nickname "daddy longlegs." Because they tend to live in dark places, such as basements, they're also often called "cellar spiders." The researchers published descriptions of these two new Pholcid species on July 24 in the journal Subterranean Biology.

Related: Are daddy longlegs really the venomous spiders in the world?

These daddy longleg spiders should not be confused with harvestmen, another type of arachnid often referred to as daddy longlegs. Unlike these Pholcid spiders, which look like regular spiders with two distinct body sections, harvestmen often look like they have a single, round body section hoisted aloft by their wire-thin legs.

The first new Pholcid spider was discovered in mining boreholes of the Pilabra, a dry and rocky habitat in a remote corner of Western Australia. The species belongs to the genus Belisana, which — prior to this study — was thought to only live hundreds of miles away, in Asia and the more vegetated northeast region of Australia.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Because this spider lives so far away from other members of its genus, the researchers think that Belisana spiders may have once been much more widespread in Australia. They speculate that the genus may have lived all across the continent about 60 million years ago, when it was covered by forests. But as western and central Australia grew drier, many of the Belisana spiders living there could have died out — except for this newfound species, Belisana coblynau, which had by then adapted to live in underground environments that hadn't changed as drastically as the surface ecosystem.

The other new species described in the paper was also found underground, but this time in a lava tube — a tunnel formed by molten lava — on Réunion, a French island off the coast of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean.

This spider is in the genus Buitinga, with its closest relatives living on the African mainland. But no Buitinga spiders are known to live on Madagascar, despite the fact that Madagascar is closer to the African mainland and much larger than Réunion. Complicating the mystery, daddy longleg spiders don't "balloon," a process in which baby spiders weave parachutes out of silk to let the wind blow them around — and a great way to travel from island to island.

Because of this, the researchers speculate that these Réunion Buitinga spiders likely ended up on the island due to a single, one-off event, like a log carrying a group of spiders across the sea or a storm carrying the spiders off the mainland in hearty gusts of wind.

Cave-dwelling animal species, including spiders, often lose their eyesight and their color as they adapt to underground habitats, Sharma said. Maintaining eyesight and producing body pigmentation requires a lot of energy, he added, and in a dark environment where there's little or no light, like a lava tube or a mining borehole, animals are often better suited putting their energy elsewhere.

For example, some animals that live underground evolve a keen sense of smell, Sharma said, which can help them get a sense of what’s happening in the dark around them.

Ethan Freedman is a science and nature journalist based in New York City, reporting on climate, ecology, the future and the built environment. He went to Tufts University, where he majored in biology and environmental studies, and has a master's degree in science journalism from New York University.