11 ways orcas show their terrifying intelligence

Orcas have their own dialect, greeting ceremonies and even wore salmon as hats in a weird fad during the 1980s.

Orcas are one of the most successful species in the seas, reigning at the top of the food chain in every ocean. And one of the reasons they are so successful is simple: they're really, really clever.

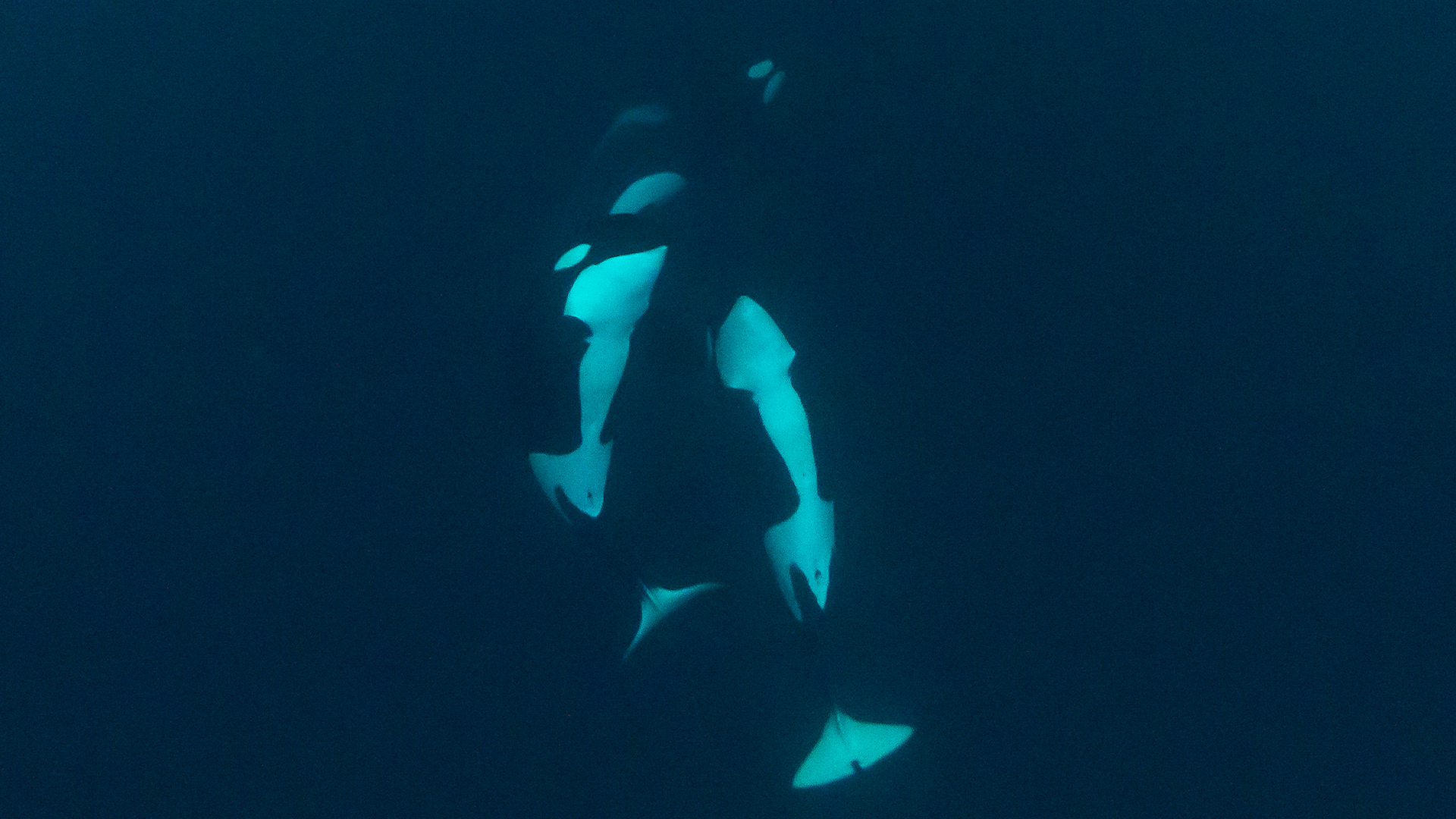

Orcas (Orcinus orca) have rich and distinct social lives and have learned a remarkable variety of hunting strategies to take down everything from blue whales to great white sharks. Here are 10 examples of orca intelligence that prove killer whales are killer smart.

Related: Orcas are learning terrifying new behaviors. Are they getting smarter?

They get caught up in fads

Orcas are social learners and occasionally get caught up in fads — a temporary behavior started by one or two individuals, adopted by others and then swiftly abandoned. For example, a population in the Pacific went through a phase of wearing salmon as hats in the 1980s. The trend started when a female orca began carrying around dead salmon on her head, and in the weeks that followed, the behavior spread to two other pods in the same community.

Researchers spotted the salmon-wearing orcas doing the same behavior the following year and then never saw them carry fish on their heads again, according to a 2004 review of nonhuman culture published in the journal Biological Conservation. Recent orca attacks on boats in Europe may be another example of a killer whale fad.

Related: Orcas attack boat with ruthless efficiency, tearing off rudders in just 15 minutes

They engage in "greeting ceremonies"

Killer whales have complicated social rituals and even engage in what researchers call "greeting ceremonies." These interactions are the orca equivalent of a mosh pit, with orcas lining up in two rows and then tumbling together, Smithsonian Magazine reported. During one such event, the greeting coincided with a birth. Three orca pods reunited in the Strait of Juan de Fuca on the boundary between the U.S. and Canada in 2020, and as the orcas whistled and clicked to each other, a pregnant female produced a calf, KUOW, Seattle's National Public Radio news station, reported. The orcas weren't foraging and appeared to be there just to socialize on the day of the birth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They have distinct dialects

Orcas live in pods based around related mothers and their descendants. Each pod has its own distinctive calls, like different dialects of the same language. The species can learn to mimic new sounds, which may help them form these dialects.

Researchers taught a captive female orca called Wikie to mimic human words like "hello" and "bye-bye," as well as the calls of some other animals. Wikie learned quickly and could reproduce some new sounds on her first attempt.

They employ specialized hunting strategies

Orcas learn highly specialized hunting strategies and pass that knowledge to their offspring. Some killer whales in Argentina beach themselves to snatch seals on the shore, while in Antarctica, other populations create waves to push seals off floating sea ice.

And it's not just seals they learn unique strategies for; killer whales are salmon specialists in parts of the Pacific, beaked whale hunters off Australia and sting-ray snatchers off New Zealand, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature's (IUCN) Red List.

Related: 'Chaos of clicks and sounds from below' as 70 orcas kill blue whale

They're picky eaters

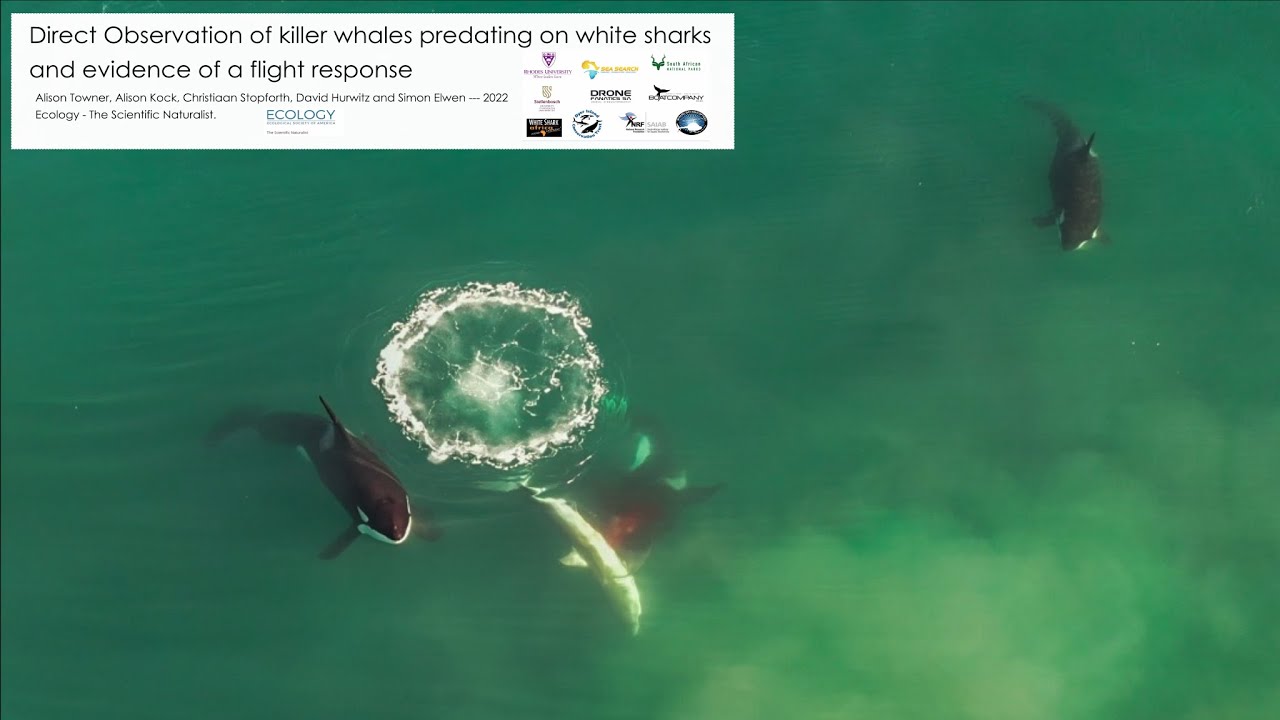

Some orca populations seem to have learned that shark livers are particularly rich in nutrients and that it's worth killing sharks and discarding the rest of their carcasses just to get to the nutritious organs. Researchers have documented killer whale populations targeting the livers of a variety of sharks, including attacking great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) off South Africa and tearing open whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) off Mexico.

They appear to have friends

A 2021 study published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B found that orca social bonds are comparable to those seen in primates, including humans. A killer whale interacts more with certain members of its pod, usually those of a similar age and of the same sex.

Michael Weiss, research director of the Center for Whale Research in Washington state, led the study and spoke to Science about two distantly related young males that were always together during the research. "Every time you see a group of whales, those two are right there interacting with each other," Weiss said. "I wouldn't hesitate to use the word friendship here."

They seem to grieve

In 2018, researchers spotted a seemingly grief-stricken female orca pushing her dead newborn calf around. The orca, named Tahlequah, pushed her lifeless calf for at least 17 days, covering 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) of ocean before she eventually let go of it. The Center for Whale Research described it as a "tour of grief."

Wildlife charity Whale and Dolphin Conservation noted on its website that researchers have documented several species of whales and dolphins carrying deceased calves or juveniles, and these "mourning behaviors" are likely common among social, long-lived mammals. Scientists have historically been reluctant to use words like "grief" for fear of projecting human emotions onto animals, BBC Earth previously reported. The motivations behind this behavior still aren't fully understood.

They can be trained

Humans have been training captive orcas for decades. At SeaWorld, for example, killer whales strike poses, splash crowds, wave their pectoral fins and generally flip-flop around on command.

Keeping killer whales in an artificial environment is controversial, with some experts arguing that it causes stress and contributes to disease. SeaWorld announced it was ending its orca captive breeding program in 2016, and the orcas it has now will be the last generation in its care.

They care for one another

Researchers have documented numerous examples of orcas supporting their fellow pod members. For example, orcas have helped injured or deformed family members survive by catching food for them, the Daily Mail previously reported. Killer whale mothers also care for their sons well into adulthood, and orca grandmothers care for their grandchildren after they go through menopause (one of a handful of species to do so).

A 2015 study published in the journal Current Biology found that older females also guide their pod members to food, especially during tough times when food is scarce, suggesting that orcas that no longer reproduce support the survival chances of the pod by imparting wisdom.

Their brains are big

A killer whale's brain can weigh as much as 15 pounds (6.8 kilograms) and is well equipped for analyzing underwater environments, the Orlando Sentinel reported in 2010. One of the species' most impressive intellectual tools involves echolocation. Orcas click to create sound waves and locate prey by detecting when those waves bounce off something. Researchers believe that southern resident killer whales, an orca population that lives off the Pacific Northwest coast, can distinguish chinook salmon from other fish by detecting the size and orientation of salmon swim bladders, which give off unique acoustic signatures, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

They hunted whales with humans

For around 1,000 years, a population of orcas off the coast of Australia hunted alongside Indigenous people, and later European whalers. They would hit the water to alert humans to the whales' presence and would sometimes tow them to their location using a rope. In exchange, the humans gave the orcas the whales' lips and tongues. The relationship became known as the "Law of the Tongue." It continued until the 1930s, by which time commercial whaling had caused baleen whale stocks to plummet. The orcas left, and this killer whale population is now believed to be dead.

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.