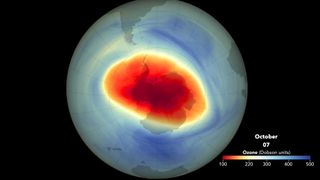

See how the huge ozone hole over Antarctica has grown in 2021 in this NASA video

A cold winter is spurring the hole, which will persist through November at least.

A new NASA video highlights the giant ozone hole that opened over Antarctica this year.

A cold Southern Hemisphere winter, and possible effects of global warming, have caused the hole to grow to its 13th-largest extent since 1979. The ozone depletion you see in the NASA video is monitored by three satellites operated by NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA): Aura, Suomi-NPP and NOAA-20.

NASA released the new video of the Antarctic ozone hole's growth on Oct. 29. It is expected this year's hole will close no earlier than late November.

Related: 10 devastating signs of climate change satellites see from space

Ozone is a naturally occurring oxygen compound (which humans can also make) that forms high in the upper Earth atmosphere. The natural type of stratospheric ozone forms when ultraviolet radiation from the sun interacts with molecular oxygen in our atmosphere. The resulting ozone acts a bit like sunscreen, shielding the Earth's surface from ultraviolet radiation.

Unfortunately, chlorine and bromine produced from human activities erode the ozone as the sun emerges over the Antarctic after the polar winter, as the sun's radiation spurs erosion in that region. The 1987 Montreal Protocol restricts ozone-depleting substances among the nearly 50 abiding nations, but a majority of world nations are not signatories; at least some of that majority do not abide by the protocols.

Still, NASA said the protocol has been helpful. "This is a large ozone hole because of the colder than average 2021 stratospheric conditions, and without a Montreal Protocol, it would have been much larger," Paul Newman, chief scientist for Earth sciences at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, said in a statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This year's ozone hole reached a peak size of roughly the size of North America, or 9.6 million square miles (24.8 million square kilometers). Annual reduction of the ozone hole began again in mid-October, NASA noted. If the Montreal Protocol had not come into force, and assuming the atmospheric substance amounts of the early 2000s, the hole would have been larger by about 1.5 million square miles (about four million square kilometers), the agency added.

Back when the protocol was signed, scientists suggested the ozone layer would recover by 2060. But the recovery is slower than anticipated and the consensus now appears to be no earlier than 2070, Vincent-Henri Peuch, director of the European Union's Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service, told Space.com in a recent interview.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

Most Popular