Beneath Greenland iceberg, scientists find a glowing snailfish with antifreeze coursing through its veins

This helps protect the tadpole-like fish from the cold.

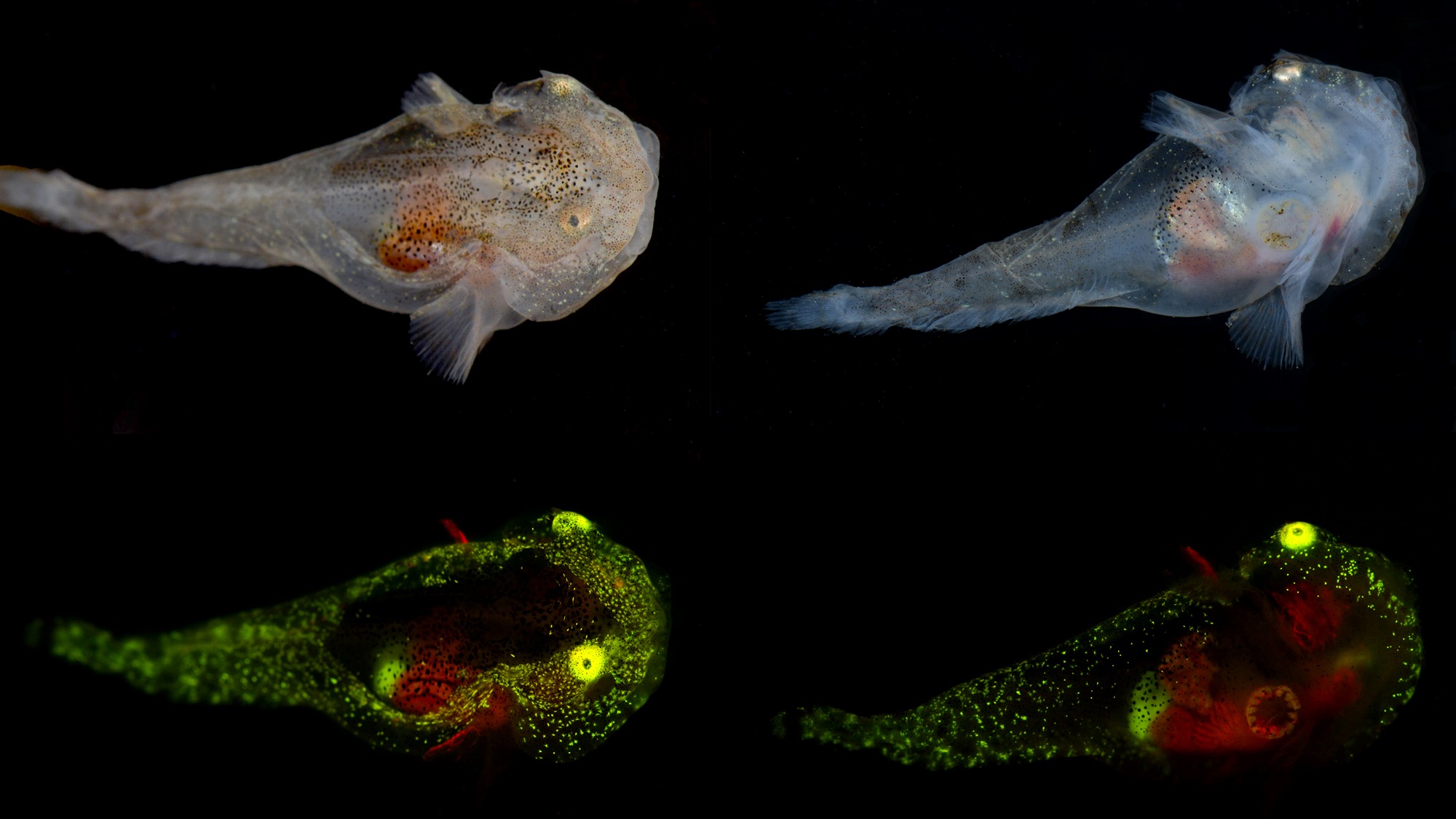

Scientists drilling deep into an iceberg off Greenland have discovered a fish with glowing green antifreeze coursing through its veins.

The juvenile variegated snailfish (Liparis gibbus) contained the "highest expression levels" of antifreeze proteins ever reported, a new study found.

Similar to how antifreeze helps to regulate the temperature of a car's engine in extreme conditions, certain species have evolved to have similar protection, especially those living in frigid habitats such as the polar waters off Greenland.

"Antifreeze proteins stick to the surface of smaller ice crystals and slow or prevent them from growing into larger, and more dangerous, crystals," study co-author David Gruber, a research associate at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) and a distinguished biology professor at City University of New York's Baruch College, told Live Science in an email. "Fish from both the North and South Poles independently evolved these proteins."

Related: Robotic sub will explore underside of Greenland's glaciers in a first

Antifreeze proteins were first discovered in some Antarctic fish nearly 50 years ago, according to the National Science Foundation.

Unlike certain cold-blooded species of reptiles and insects, fish are unable to survive when their bodily fluids freeze, which can cause grains of ice to form inside their cells and essentially turns them into fish Popsicles.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The fact that these different antifreeze proteins have evolved independently in a number of different — and not closely related — fish lineages show[s] how critical they are to the survival of these organisms in these extreme habitats," John Sparks, a curator in the AMNH's Department of Ichthyology and co-author of the study, told Live Science in an email.

Snailfish produce antifreeze proteins "like any other protein and then excrete them into their bloodstream," Gruber said. However, snailfish appear to be "making antifreeze proteins in the top 1% of all other fish genes."

Scientists found the tiny tadpole-like creature in 2019 during an expedition as they explored the iceberg habitats off the coast of Greenland. During the trip — which was part of the Constantine S. Niarchos Expedition, a series of science-based expeditions led by the AMNH — the scientists were flummoxed when they discovered the biofluorescent snailfish glowing brilliant green and red in the icy habitat.

"The snailfish was one of the few species of fish living among the icebergs, in the crevices," Gruber said. "It was surprising that such a tiny fish could live in such an extremely cold environment without freezing."

It's also rare for Arctic fishes to exhibit biofluorescence, which is the ability to convert blue light into green, red or yellow light, since there are prolonged periods of darkness, especially in the winter, at the poles. Normally this characteristic is found in fish swimming in warmer waters. This is the first reported case of an Arctic fish species exhibiting this adaptation, according to an AMNH post.

The scientists further examined the biofluorescent properties of the snailfish and found "two different types of gene families encoding for antifreeze proteins," according to a separate statement, an adaptation that essentially helps them avoid turning into frozen fish sticks.

This mind-boggling level of antifreeze production could help this species adapt to a subzero environment, according to the statement. It also raises a question about how snailfish will fare as ocean temperatures increase as a result of global warming.

"Due to rapidly warming waters in the Arctic, these cold-water-adapted species will also have to compete with warmer-water species that are now able to migrate north and survive at higher latitudes (and that won't need to produce metabolically costly antifreeze proteins to survive in the warmer Arctic waters)," Sparks said. "In the future, [antifreeze] proteins may no longer provide an advantage."

The findings were published Aug. 16 in the journal Evolutionary Bioinformatics.

Originally published on Live Science.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.