Antikythera Mechanism photos: See the world's first computer

Sponge divers pulled the first fragments of what became known as the Antikythera Mechanism from a Roman-era shipwreck in 1901 off the coast of the Greek island Antikythera. Ever since the discovery, scientists and historians have continued to look for more artifacts from the shipwreck while also piecing together the story of what is often considered the world's first computer.

Scientists figured out years ago that the device was a bronze astronomical calculator that may have helped the ancient Greeks track the positions of the sun and the moon, the lunar phases and even cycles of Greek athletic competitions. Researchers reported in 2021 they had created the first complete digital model of the so-called Cosmos panel of the 2,000-year-old mechanical device. And they found a well-preserved skeleton of a young man (possibly part of the ship's crew) that could provide the first DNA evidence from the sunken boat. The 82 corroded metal fragments of the mechanism also contain inscriptions that scientists have continued to decipher. Here's a look at the mysterious device and information scientists have uncovered about it.

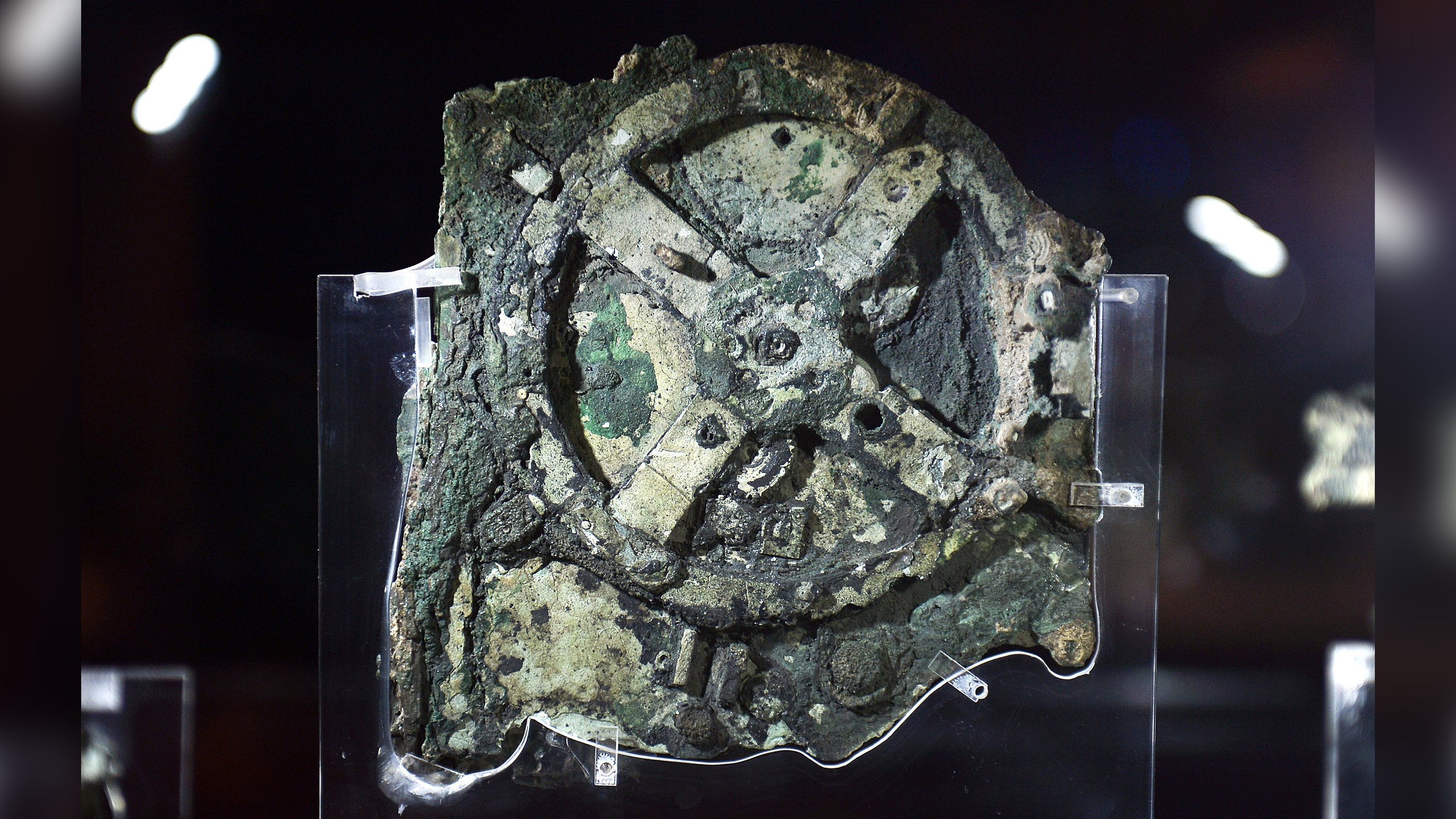

Corroded panel

The most well-known piece of the Antikythera Mechanism is shown at the Archaeological Museum in Athens. The contraption held 37 interconnected gears that scientists found would have helped ancient people to follow heavenly bodies.

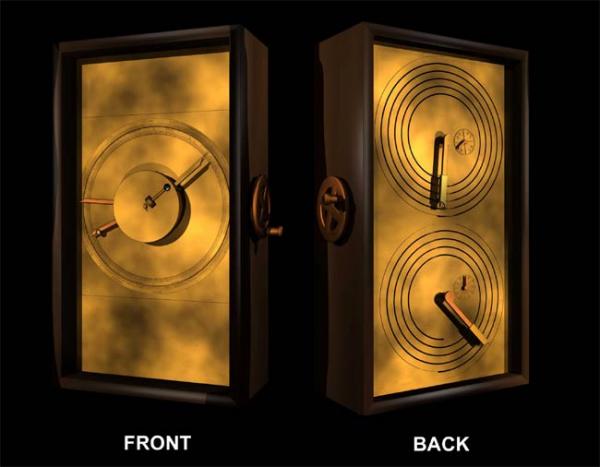

Hand-cranked computer

The Antikythera mechanism, shown here in this computer reconstruction, was about the size of a shoebox, with dials on its exterior and an intricate system of 30 or so bronze gear wheels inside. Though it was found in several corroded fragments, scientists have used imaging and other technologies to piece the machine together and even decode its inscriptions. When it was in use, a user of this "computer" could have turned a hand crank and tracked the positions of the sun and the moon, the lunar phases, and even cycles of Greek athletic competitions.

Exosuit

In September 2014, scientists explored the Antikythera shipwreck, looking for sunken statues, gold jewelry and other ancient artifacts lost in the Agean Sea. For the mission, they used the Exosuit that allowed the operator to safely descend hundreds of feet below the surface of the Aegean Sea.

Shipwreck dive

Phil Short piloted the Exosuit near the end of the "Return to Antikythera" mission, which lasted from Sept. 15 to Oct. 7, 2014.

Finding artifacts

During the dive near the shipwreck, scientists found a bronze spear. The spear would have been too big and heavy to be a functional weapon 2,000 years ago, and so it likely was part of a statue, the researchers said.

Big haul

Here, an archaeologist swims over artifacts at the site of the Antikythera shipwreck. A trove of artifacts have been found associated with the shipwreck. In 2015, researchers pulled up 50 objects from the depths as part of their scientific excavation of the Antikythera wreck site.

Wine decanter

During the 2014 mission, divers used rebreather technology, which recycles air, while exploring the Antikythera wreckage. The technology let the divers stay underwater for up to three hours at a time, so they could dig up artifacts like this lagynos. The lagynos was a distinctive Hellenistic ware that was used to pour wine.

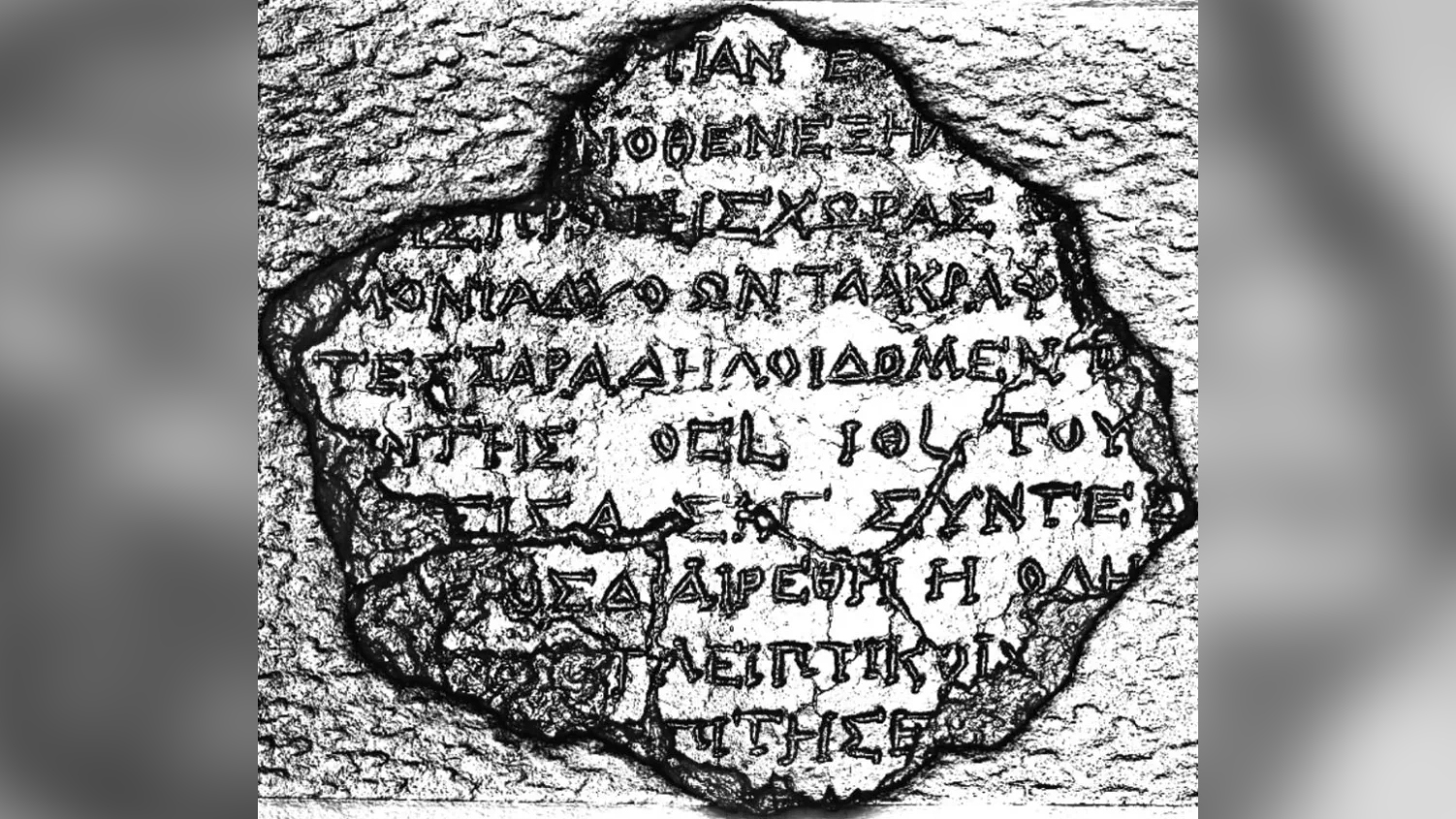

Inscriptions revealed

Called fragment 19, this is a piece of the device's back cover. Using a technique called polynomial texture mapping, or PTM, researchers could create a much clearer visualization of the Antikythera inscription. With PTM, different lighting conditions can be simulated to reveal surface details on artifacts that might otherwise be hidden.

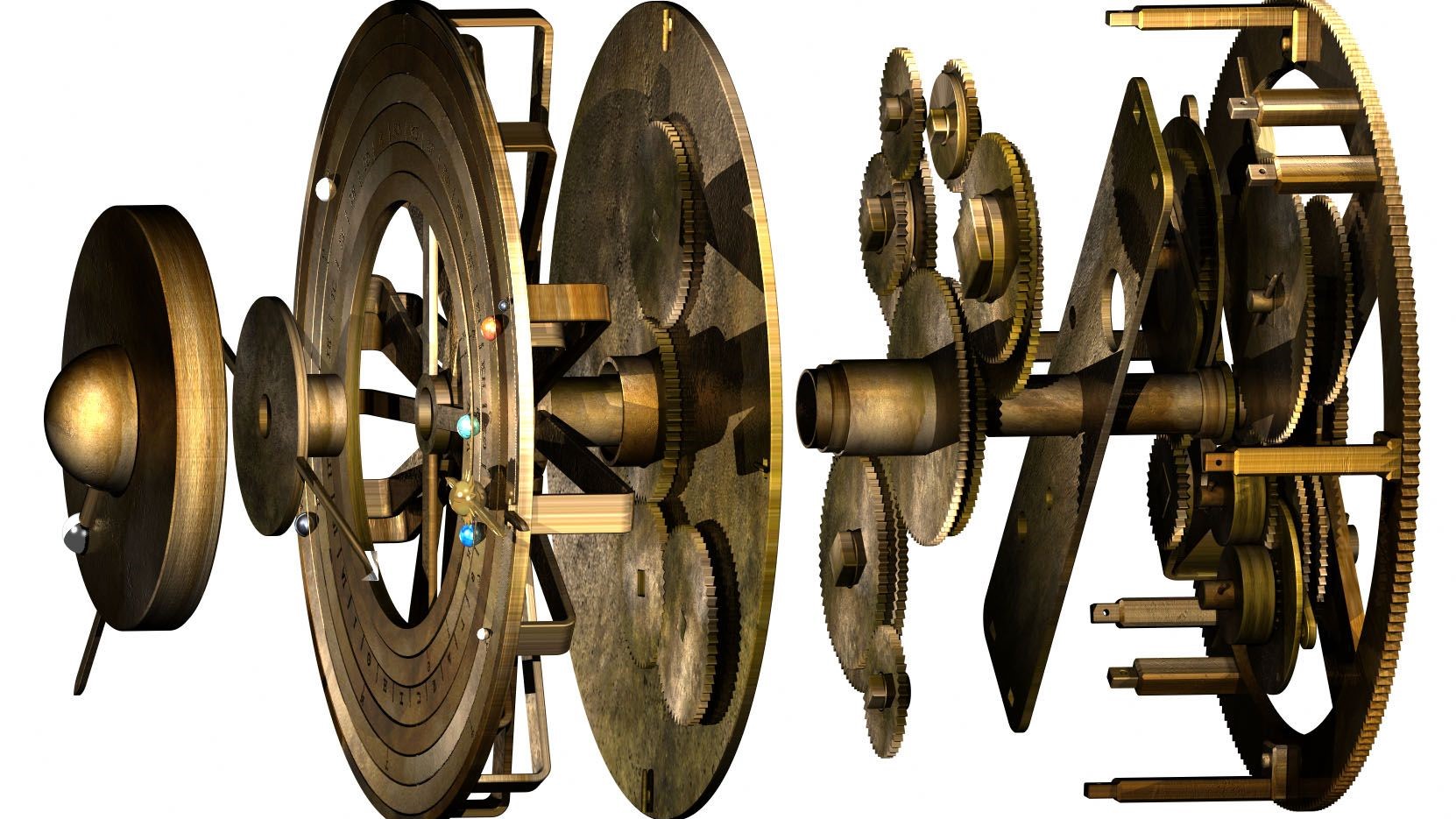

1st model

Researchers at University College London reported in 2021 that they used ancient calculations to fully recreate the design of the Antikythera mechanism. They now hope to piece together their own contraption based on the design. Will it work? Each gear in the mechanism should chart the movement of a heavenly body.

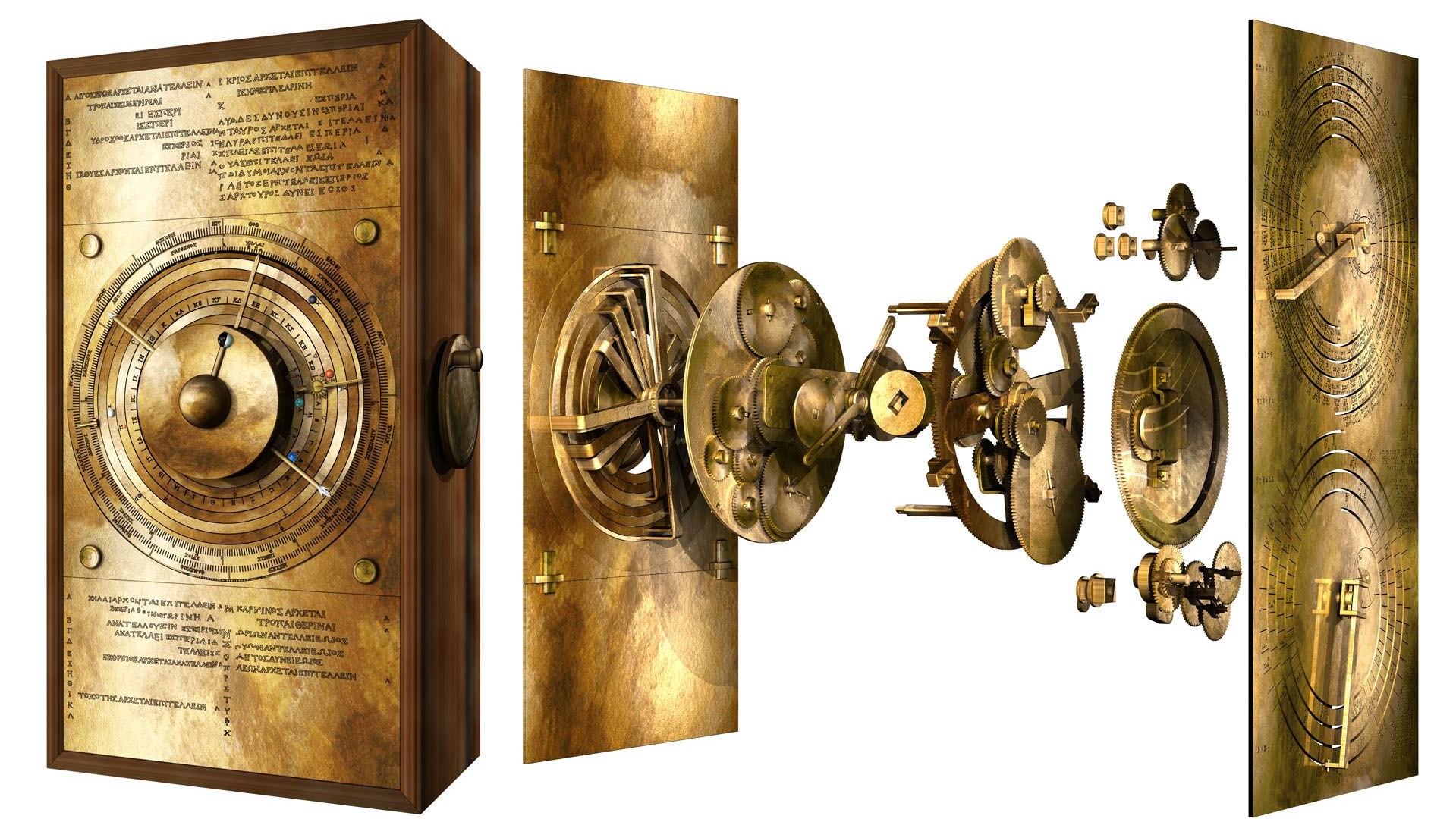

Inside Antikythera

This is what the Antikythera mechanism would have looked like if pulled apart some 2,000 years ago.

Originally published on Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

- Megan GannonLive Science Contributor