1.4 million-year-old jaw that was 'a bit weird for Homo' turns out to be from never-before-seen human relative

The newfound species belongs to the genus Paranthropus, whose nickname is "nutcracker man."

A 1.4 million-year-old fossil jaw belongs to a previously unknown human relative from southern Africa, a new study finds.

The extinct human relative is from the genus Paranthropus, whose nickname is "nutcracker man" because of its massive jaws and huge molars. However, the newfound Paranthropus species has a more diminutive jawbone and teeth, indicating that the nutcracker moniker might not be so apt after all.

At the time Paranthropus was alive, the world had several hominins, or species on the evolutionary branch more closely related to humans than to chimps. Our genus, Homo, emerged at least 2.8 million years ago, while our species, Homo sapiens, dates back to at least 300,000 years ago. So early Homo species overlapped with Paranthropus. Until now, scientists knew of three Paranthropus species — P. aethiopicus, P. boisei and P. robustus — which lived between about 1 million and 2.7 million years ago.

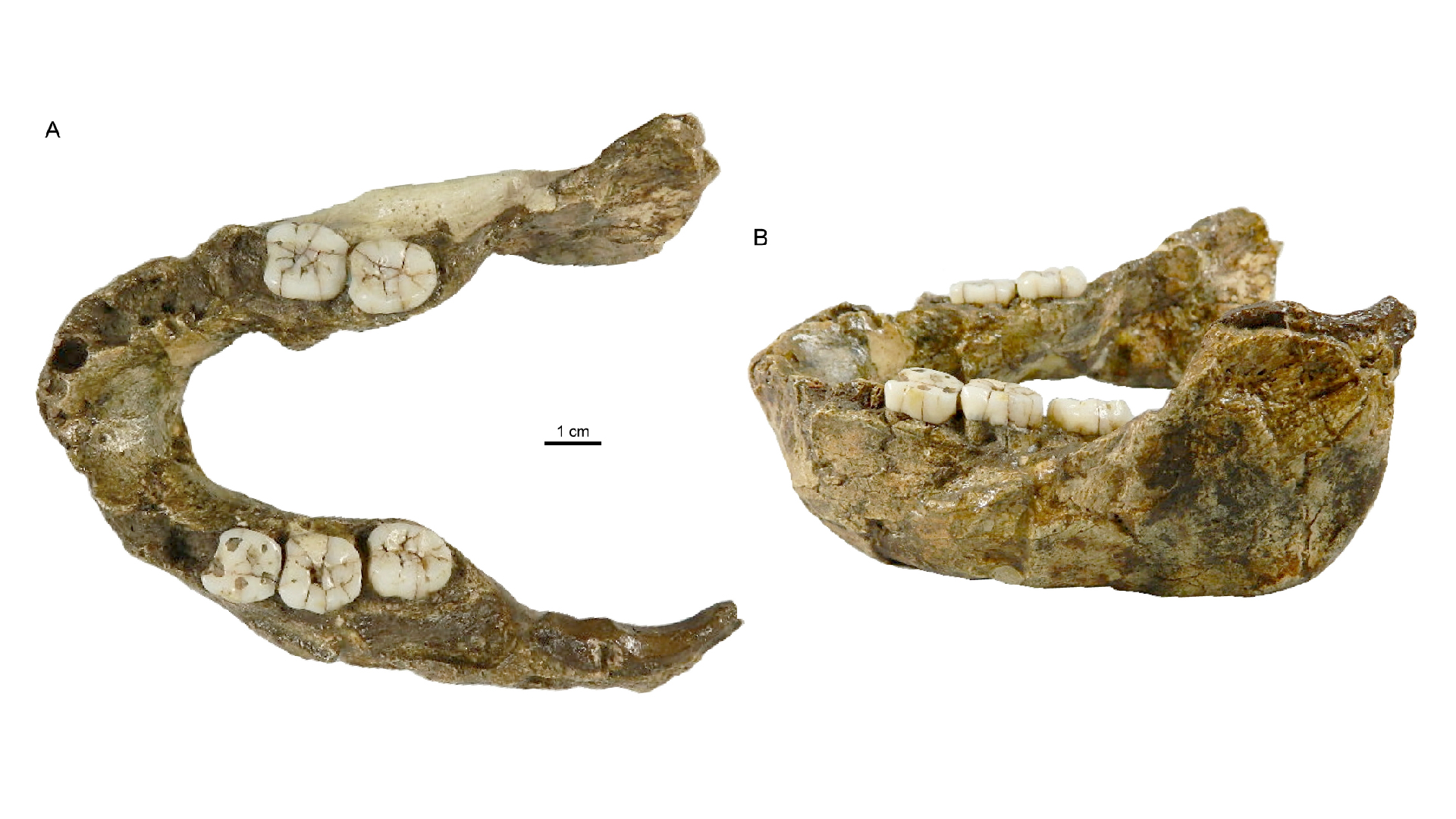

In the new study, researchers examined a 1.4 million-year-old jaw dubbed SK 15. The bone was originally unearthed in 1949 in a cave at a South African site known as Swartkrans, alongside other Paranthropus fossils and a few early Homo specimens.

"Swartkrans is thus a key site to uncover the extent of hominin diversity and understand the potential interactions among various hominin species," study lead author Clément Zanolli, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Bordeaux in France, told Live Science.

Initially, scientists thought SK 15 belonged to a never-before-seen species they called Telanthropus capensis. However, since the 1960s, researchers suggested it actually belonged to the relatively slender early human species known as Homo ergaster.

Related: Why did Homo sapiens outlast all other human species?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Zanolli and his colleagues performed X-ray scans of SK 15 and other fossils so they could create virtual 3D models of the specimens and better understand their internal and external structures. Unexpectedly, they found that SK 15 was likely not H. ergaster but a previously unknown species of Paranthropus.

"This is the first time since the 1970s that a new species of Paranthropus was identified," Zanolli said. The scientists detailed their findings in the March issue of the Journal of Human Evolution.

Although SK 15's external structure resembles H. ergaster, it looks "a bit weird for Homo," Zanolli said. For instance, SK 15 is extremely thick compared with any other Homo jaw. In addition, SK 15's molars are quite long and rectangular, whereas Homo molars are more rounded, Zanolli said.

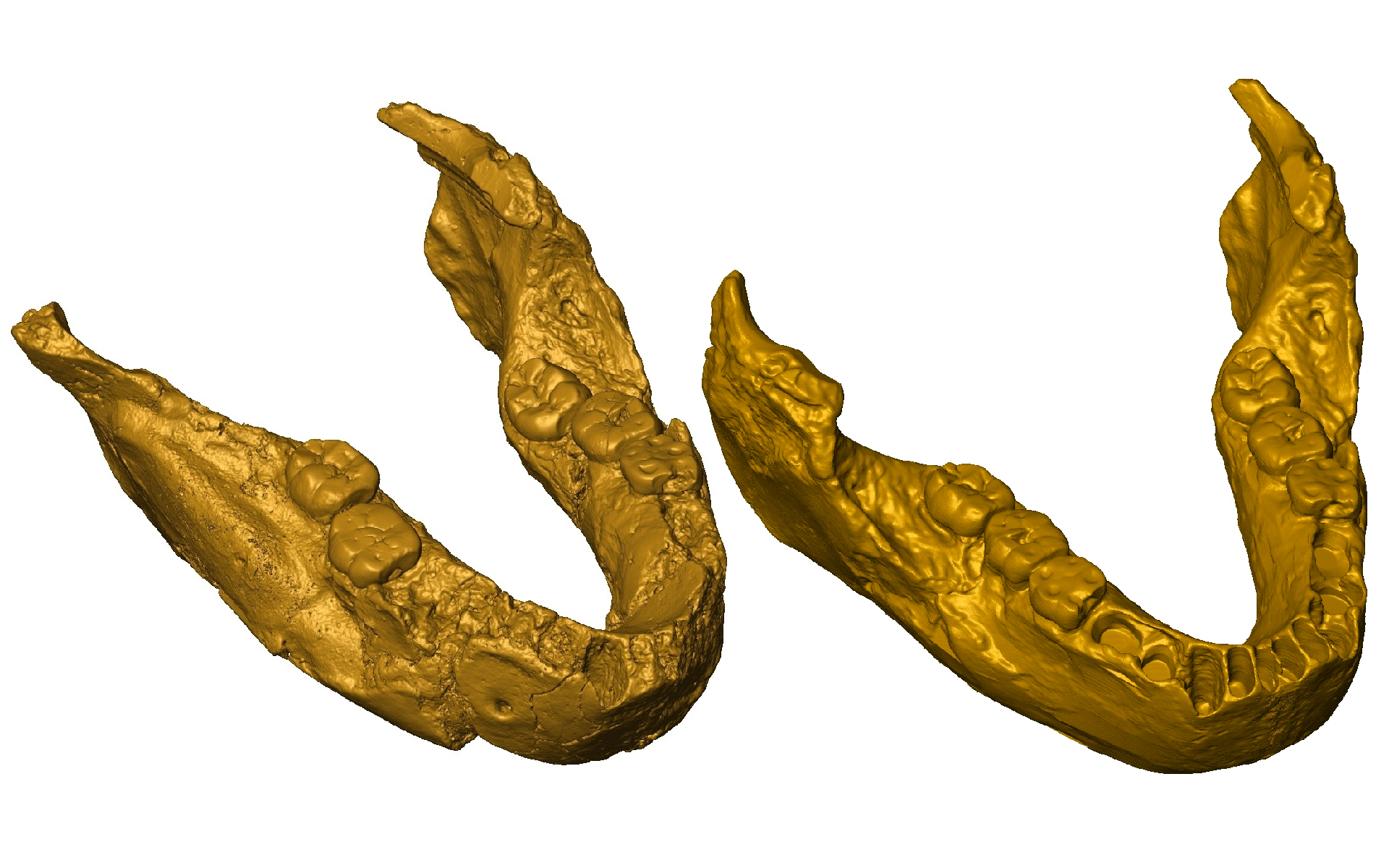

A digital 3D model of SK 15's jaw (left) and a reconstruction of the same jaw (right), which "repairs" where it was fractured during the fossilization process.

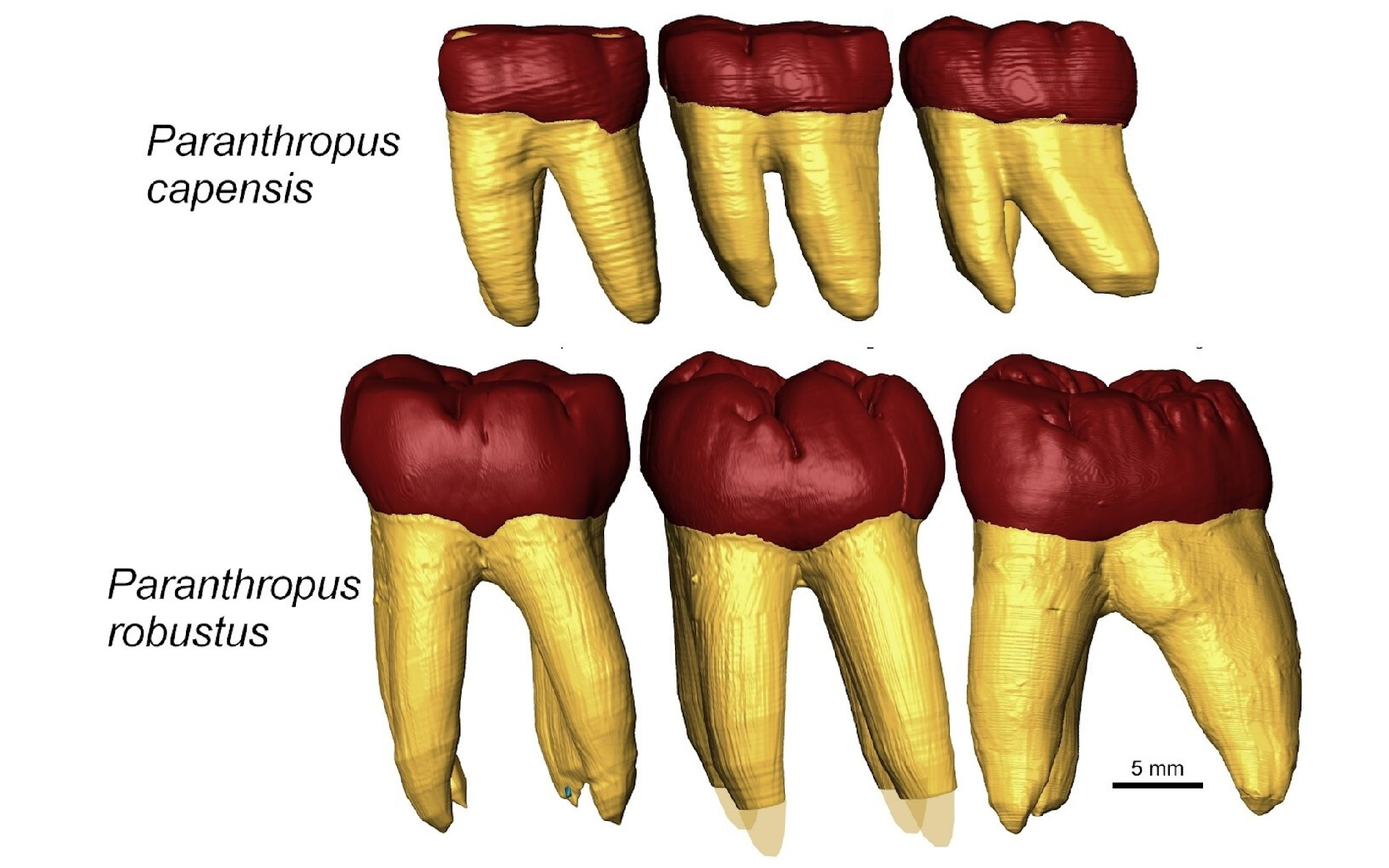

The molars of Paranthropus capensis (top) are smaller, shorter and have different roots than those of Paranthropus robustus (bottom). But they have similarly shaped crowns.

The researchers examined the internal structure of SK 15's teeth — specifically, the portion of the dentine, the hard, dense, bony tissue forming the bulk of a tooth, below the enamel in the crown of the teeth. They found that this did not match any known Homo specimen, revealing that the fossil was not from H. ergaster, Zanolli said.

Instead, based on the jaw shape and the sizes and shapes of the crowns and roots of the teeth, SK 15 likely belonged to Paranthropus. However, it looked different from any known Paranthropus specimen — for instance, the jaw and teeth are significantly smaller.

These findings suggest SK 15 does not belong to any of the three recognized Paranthropus species. The researchers suggest it belongs to a newfound species, which they named P. capensis.

The findings suggest at least two Paranthropus species coexisted in southern Africa about 1.4 million years ago — P. robustus and P. capensis.

"They probably had different ecological niches," Zanolli said. P. robustus likely had a highly specialized diet, "as suggested by the massive jaw and teeth, while P. capensis, which displays smaller teeth and a less robust mandible, might have had a more varied diet and potentially exploited different food resources," Zanolli added.

Future research might reveal whether P. capensis was an evolutionary dead end or not, but this is difficult to determine at the moment, as the early hominin fossil record is "scarce for all of Africa," Zanolli said. There might be species of Paranthropus "that survived much longer than we currently know."

Test your knowledge of Homo sapiens

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Live Science and Space.com. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a master of arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a bachelor of arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.