1.5 million-year-old bone tools crafted by human ancestors in Tanzania are oldest of their kind

The discovery of 1.5 million-year-old bone tools upends what we know about tool manufacturing in East Africa.

The oldest human-crafted bone tools on record are 1.5 million years old, a finding that suggests our ancestors were much smarter than previously thought, a new study reports.

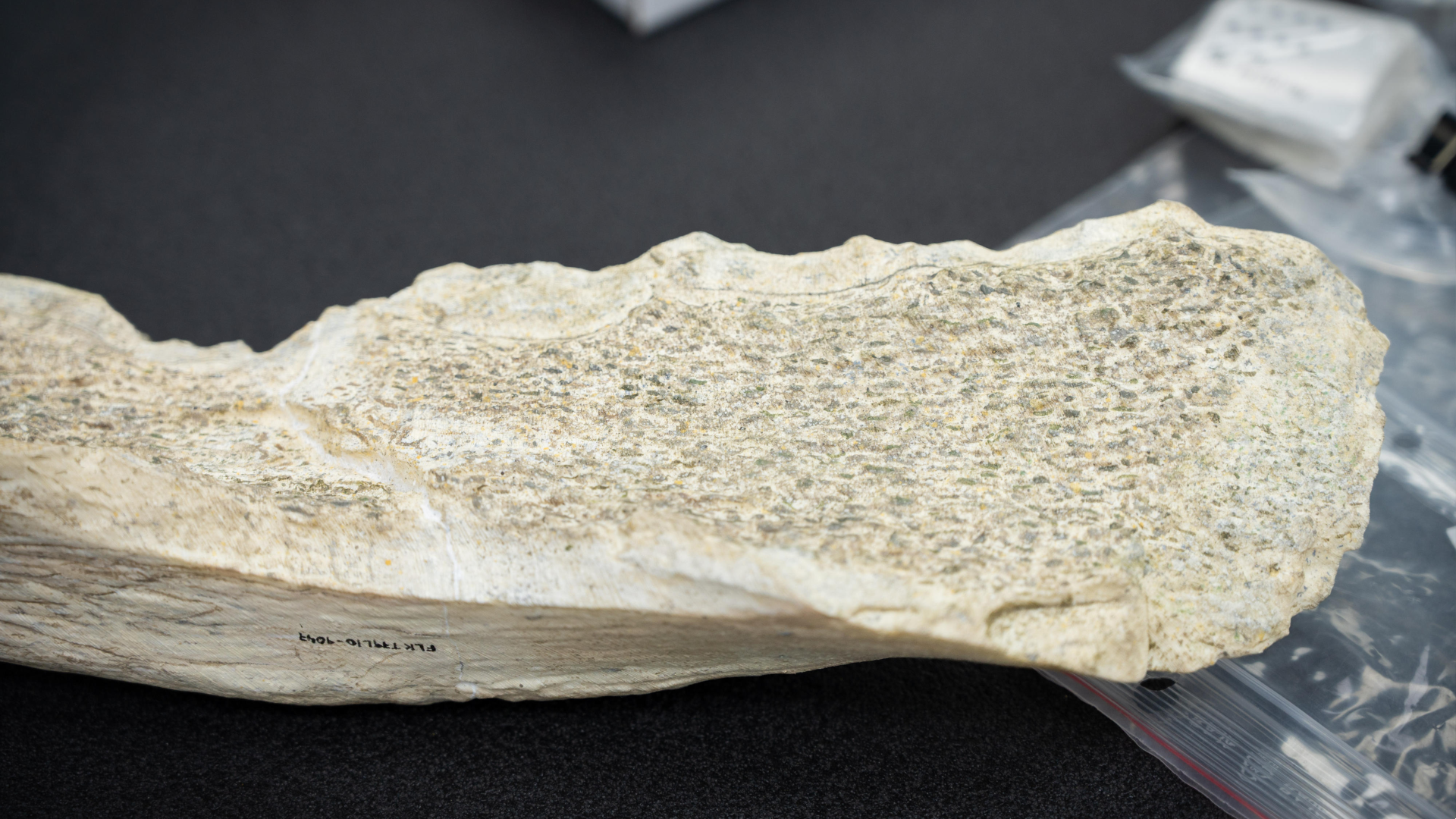

The tools, made from hippo and elephant leg bones, were discovered at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania and are a million years older than any previously found shaped bone tools.

The hominins who created these tools "knew how to incorporate technical innovations by adapting their knowledge of stone work to the manipulation of bone remains," study first author Ignacio de la Torre, a paleolithic archaeologist at the Centre for Human and Social Sciences of the Spanish National Research Council, said in a statement. The finding indicates "advances in the cognitive abilities and mental structures of these hominins."

The researchers studied 27 bone fragments that had been turned into tools through a process used in stone tool manufacturing called knapping. This technique involves using one larger stone to break pieces off a smaller stone, achieving a sharp edge around the latter.

Although evidence of stone tool knapping goes back at least 3.3 million years in East Africa, only a handful of bone tools shaped by the same process have been found, likely because bone usually decays over time. These fragments of bone may have been preserved because they were buried quickly.

But when de la Torre and colleagues looked closely at more than two dozen bits of bone, they were able to show that the removal of bone flakes was not caused by carnivore activity but by hominins purposely shaping the bone. They published their findings Wednesday (March 5) in the journal Nature.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers were further able to narrow down the species of animals used to make the bone tools: eight were made out of elephant bones, six from hippos and two from a cow-like species. Since most of the non-tool animal bones were from bovids, this suggests that the elephant and hippo bones were specifically selected for their tool-making properties, such as their length and thickness.

Tools made from elephant bones range from 8.6 to 15 inches (22 to 38 centimeters) long, while the hippo bone tools are slightly shorter at 7 to 11.8 inches (18 to 30 cm) long. These may have been used as heavy-duty tools for processing animal carcasses, the researchers suggested. But it's unclear which hominin species made the tools — both Homo erectus and Paranthropus boisei lived in the Olduvai Gorge region 1.5 million years ago, long before modern humans appeared on the scene.

The discovery of knapped bone tools over a million years earlier than expected has important consequences for our understanding of human evolution, according to the study. Prior to creating large stone tools like hand-axes, it appears that early hominins tested out their knapping skills on bone, an innovation that had previously been invisible at archaeological sites in East Africa.

"We were excited to find these bone tools from such an early timeframe," study co-author Renata Peters, an archaeologist at University College London, said in the statement. "It means that human ancestors were capable of transferring skills from stone to bone, a level of complex cognition that we haven't seen elsewhere for another million years."

Human evolution quiz: What do you know about Homo sapiens?

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Killgrove holds a PhD in biological anthropology and an MA in classical archaeology, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.