1,500 ancient European genomes reveal previously hidden waves of migration, study finds

Researchers developed a more precise method of understanding ancestry from ancient DNA and used it to identify previously unknown waves of migration.

Researchers have identified three major waves of migration in early Europe, using a new technique to analyze human genomes. The analysis revealed that Scandinavia was a crucial hotspot for people as they traveled northward and dispersed elsewhere during the first millennium.

In a study published Wednesday (Jan. 1) in the journal Nature, the researchers detailed a new approach to understanding ancient DNA. They applied the method — called "time-stratified ancestry analysis" using a statistical technique called Twigstats — to over 1,500 previously published genomes. This technique allowed the team to uncover waves of migration and ancestry information that other methods had obscured.

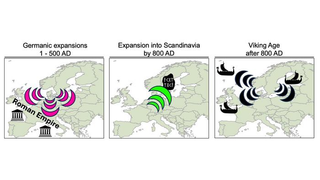

The three major waves of migration encompassed the entire continent, according to the Twigstats analysis. First, the researchers found considerable expansion of people from southern Scandinavia and Northern Europe into the rest of the Roman Empire between A.D. 1 and 500. They identified a second wave of migration from Eastern and Central Europe into Scandinavia that ended around A.D. 800. People then expanded out of Scandinavia once again in the Viking Age (post-800).

The method can identify unknown ancestry not just in whole populations but also in specific individuals, the team noted.

One genome in the study came from a Roman-era man who was buried in a "gladiator" cemetery in York, England, with his decapitated head placed between his knees. Previous research suggested that he had as much in common genetically with modern Dutch people as he did with Anglo-Saxons. The new method validated this suggestion by revealing that the man had roughly one-quarter Scandinavian-related ancestry.

"This documents that people with Scandinavian-related ancestry already were in Britain before the fifth century CE," the researchers wrote in the study.

Related: Attila the Hun raided Rome due to starvation, not bloodlust, study suggests

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The "Twigstats" technique

The Twigstats technique is novel because it statistically models genetic mutations that are shared on "twigs" of a genealogical tree. By including the time period as a factor in the analysis, it becomes feasible to identify an ancient person's ancestry more specifically and with greater certainty than previously possible.

Study co-author Pontus Skoglund, group leader of the Ancient Genomics Laboratory at the Francis Crick Institute in London, said in a statement that "the goal was a data analysis method that would provide a sharper lens for fine-scale genetic history."

The researchers applied their new method to hundreds of genomes to answer questions about the history of early medieval Europe. In particular, they wanted to know more about the groups of people who lived just outside the Roman Empire before its fall in the fifth century, since little is known about them historically.

With the information the researchers gleaned from their new method of analyzing ancient genomes, they concluded that migrations in the early first millennium may have been triggered by people in Northern Europe who were attracted by the greater wealth of the Roman Empire, while later migrations spread from Central to Northern Europe.

"Twigstats allows us to see what we couldn't before," such as these three major migrations, study first author Leo Speidel, group leader at RIKEN, a national scientific research institute in Japan, said in the statement. "Our new method can be applied to other populations across the world and hopefully reveal more missing pieces of the puzzle."

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Killgrove holds postgraduate degrees in anthropology and classical archaeology and was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.