1,500-year-old tomb in Peru holds human sacrifices, including strangled son next to father's remains, genetic analysis reveals

A genetic analysis of six people buried in a Moche tomb around A.D. 500 revealed that two teenagers were sacrificed to their close relatives.

Two teenagers who were strangled 1,500 years ago as part of an ancient Andean funeral rite were closely related to the adults they were buried with, according to a new genetic study. But surprisingly, it seems that the adolescent boy was sacrificed upon his father's death and the adolescent girl was sacrificed when her aunt died — in a ritual archaeologists have never seen before.

The buried people belonged to the Moche culture, which flourished along the north coast of Peru from A.D. 300 to 950. There is abundant evidence from iconography and archaeology that the Moche practiced human sacrifice to honor their gods, but less information about potential sacrifices made during the funeral of high-status people.

"Most of what we know about human sacrifices with the Moche relates to very public and gruesome forms of human sacrifice," study co-author Lars Fehren-Schmitz, an archaeogeneticist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, told Live Science in an email. "No evidence has pointed to the sacrifice of close or adolescent relatives like we observed," he said. "There is also no other observation like this reported in the archaeological literature."

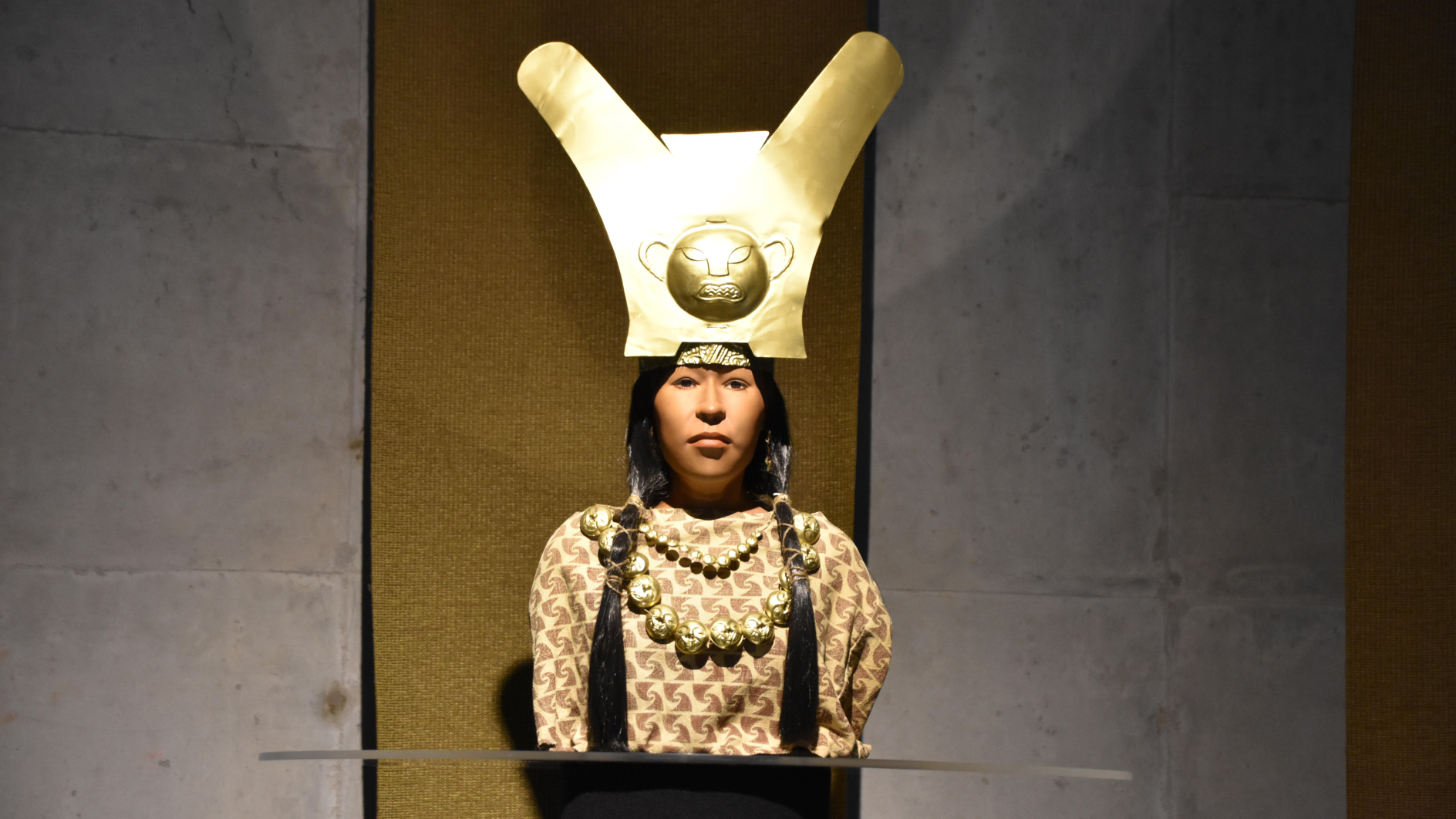

The sacrificial victims were interred in a tomb below a pyramid-like painted structure called Huaca Cao Viejo, discovered in Peru in 2005. It held the remains of six people, including the well-preserved body of a high-status woman nicknamed Señora de Cao [Lady of Cao]. Three men were also placed in the tomb, as well as two adolescents who had been strangled with plant fiber ropes.

Experts had long assumed that elite Moche burial groups like this one consisted of related family members, but the new study, published Monday (Dec. 23) in the journal PNAS, is the first to scientifically prove this, after researchers conducted genetic analysis to determine how six people in the tomb were related.

Related: Syphilis originated in the Americas, ancient DNA shows, but European colonialism spread it widely

The researchers first dated the skeletons using radiocarbon analysis, discovering that five of them were buried around the same time. Next, by sequencing the genomes of everyone in the tomb, the team was able to infer biological relatedness and create a family tree. Genomic analysis revealed that Señora de Cao was related to the adolescent girl who was sacrificed to her — they were likely aunt and niece.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Two of the men found in the tomb were likely Señora de Cao's brothers, according to the study, and one of them may have been the father of the sacrificed girl. A third man, who died decades earlier based on radiocarbon analysis of his bones, may have been the siblings' father or grandfather.

While burying related people in a family tomb is not unusual, the relationship between one of Señora de Cao's brothers and his sacrificial victim is unprecedented: Researchers discovered that the boy had been sacrificed to his father.

"There are other high status burial contexts associated with the Moche where sacrifice by strangulation has been postulated," Fehren-Schmitz said. "The idea is that this is a more private and dignified form of ritual killing probably reserved for individuals of higher societal or religious/spiritual status."

The question of why they sacrificed relatives is one the research team hopes to explore in the future, Fehren-Schmitz said, along with investigating other high-status burials to see if familial sacrifice was a common practice among the Moche elite.

"Also keep in mind that the people who arranged for the sacrifices and burials were not the same people who were sacrificed and buried," study co-author Jeffrey Quilter, curator of anthropology at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, told Live Science in an email. "So some kind of court intrigue could have led to the outcomes we found in the burials."

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Killgrove holds postgraduate degrees in anthropology and classical archaeology and was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.