1,800-year-old silver amulet could rewrite history of Christianity in the early Roman Empire

A silver amulet found next to a skeleton in a 1,800-year-old grave in Germany speaks to the importance — and the risk — of being Christian in Roman times.

A 1,800-year-old silver amulet discovered beneath the chin of a skeleton in a cemetery in Germany is the oldest evidence of Christianity north of the Alps, according to a new study.

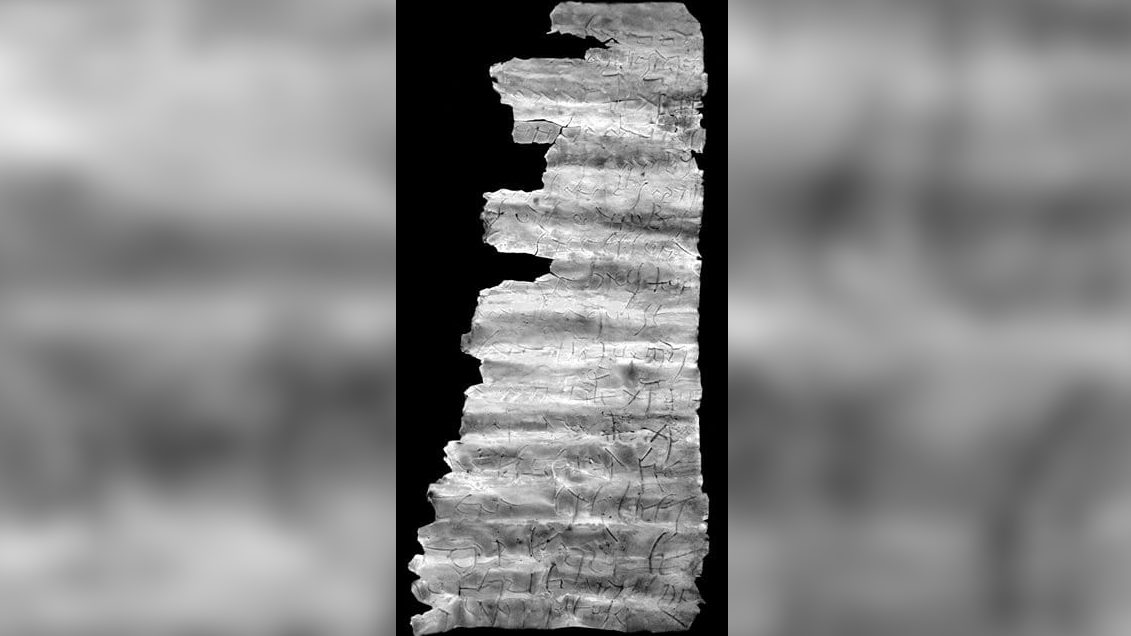

Researchers made the discovery by digitally unrolling a tiny scroll inside the amulet using CT scanning technology; this revealed an unusual Latin inscription. The finding may upend historians' understanding of how Christianity was practiced in the early Roman Empire.

Measuring just 1.4 inches (3.5 centimeters) long, the amulet contains a wafer-thin sheet of silver foil that's rolled up tightly. Archaeologists discovered it in the grave of a man who died between A.D. 230 and 270. The man likely wore the amulet on a cord around his neck, as it was found just below his jaw.

Magical amulet warded off evil

The purpose of these amulets, also known as phylacteries, "was to protect or heal their owners from a range of misfortunes, such as illnesses, bodily aches, infertility, or even demonic forces," Tine Rassalle, an independent biblical archaeologist who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. "In an era without advanced medical knowledge, such items were vital sources of comfort and security for you and your loved ones."

The location of the artifact's discovery is rare, she added.

"These amulets were widely used in Late Antiquity, especially in the eastern Mediterranean world," Rassalle said, but "they are much rarer in the western Roman world. The discovery of this amulet in Germany suggests that Christian ideas had already begun to penetrate areas far from Christianity's early centers of growth."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: 1,500-year-old Anglo-Saxon burial holds a 'unique' mystery — a Roman goblet once filled with pig fat

One man took his Christian faith to the grave

The object was discovered in 2018 during excavation of a Roman-era cemetery outside of Frankfurt. In the grave, archaeologists also found an incense bowl and a pottery jug. But the silver amulet caught the archaeologists' attention.

Experts at the Leibniz Center for Archaeology (LEIZA) in Mainz spent several years conserving, restoring and analyzing the amulet before announcing their findings in a statement Wednesday (Dec. 11).

"The challenge in the analysis was that the silver sheet was rolled, but after around 1800 years, it was of course also creased and pressed," Ivan Calandra, head of the imaging platform at LEIZA, said in the statement. "Using CT, we were able to scan it at a very high resolution and create a 3D model."

The virtual 3D model enabled scientists to digitally unroll and analyze the inscription. The 18-line inscription was deciphered by Markus Scholz, a professor at the Goethe University Institute of Archaeological Sciences in Frankfurt. He said it's unusual that the writing is in Latin. "Normally, such inscriptions on amulets were written in Greek or Hebrew," Scholz said in the statement.

Frankfurt inscription finally translated

The "Frankfurt inscription" reads as follows (the question marks signify areas of uncertainty):

(In the name?) of Saint Titus. Holy, holy, holy! In the name of Jesus Christ, Son of God! The Lord of the world resists with [strengths?] all attacks(?)/setbacks(?). The God(?) grants entry to well-being. May this means of salvation(?) protect the man who surrenders himself to the will of the Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, since before Jesus Christ every knee bows: those in heaven, those on earth and those under the earth, and every tongue confesses (Jesus Christ).

In the early days of the Roman Empire, practicing Christianity could be risky. The Roman emperor Nero persecuted Christians in the first century A.D.; some were crucified, and some were forced to fight in the Colosseum. This created an atmosphere of fear among early Christians, which forced them to practice in secret, in places like the catacombs in Rome. The fact that this man in third-century Germany was buried with his amulet meant his faith was very important to him, according to the researchers.

Amulet is rare in Western Europe

A similar silver amulet was discovered in 2023 in Bulgaria. Dated to roughly the same time, the Bulgarian amulet was also found in a grave near the person's skull. The inscription mentioned the archangels Michael and Gabriel and referenced the "guardian" Christ. Experts studying the Bulgarian amulet suggested this language as well as the placement of the amulet in a grave stemmed from the need for early Christians to conceal and guard their faith.

Other early metal amulets that have been found in the early Christian world often mix different faiths, including elements of Judaism and paganism alongside Christianity. According to the researchers, the Frankfurt amulet does not mention any other faith; it is purely Christian.

"What makes this particular example remarkable is that it is written entirely in Latin and exclusively invokes Jesus Christ and the Christian god," Rassalle said, which is unusual because most amulets "also appeal to angels, demons, or other supernatural entities."

Inscription may rewrite history of Christianity in Germany

The text of the Frankfurt amulet is therefore incredibly important for scholars of early Christianity, the researchers noted, particularly because it contains the earliest example of certain phrases, including "Holy, holy, holy!" — which is not known in Christianity until the fourth century — and an early quotation from Paul's Letter to the Philippians.

"This takes our understanding of Western Christianization and Christian monotheism to a whole new level!" Rassalle said.

"The 'Frankfurt Inscription' is a scientific sensation," Frankfurt Mayor Mike Josef said in the statement. "Thanks to it, the history of Christianity in Frankfurt and far beyond will have to be turned back by around 50 to 100 years. The first Christian find north of the Alps comes from our city: we can be proud of this, especially now, so close to Christmas."

Editor's Note: This story was originally published on Dec. 15 and updated on Dec. 20 to include new images and information about the excavation.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Killgrove holds postgraduate degrees in anthropology and classical archaeology and was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.