10 fascinating discoveries about Neanderthals in 2024, from 'Thorin' the last Neanderthal to an ancient glue factory

This year, we learned that our Neanderthal cousins were a lot like us, despite treading their own path that ended in extinction.

People have been fascinated by Neanderthals ever since we discovered their bones in a German cave in the mid-19th century. Their stocky bodies and huge heads give us a fun-house-mirror glimpse into the evolutionary road we might have traveled. Even though DNA research has shown that all modern-day human populations have a little Neanderthal in them, we still view our Neanderthal cousins as the black sheep lineage of the Homo genus.

Here's a look at 10 things we've learned about our closest known relatives — and, by extension, ourselves — this year.

Related: Lucy's last day: What the iconic fossil reveals about our ancient ancestor's last hours

1. Neanderthals had a keen sense of fashion.

Neanderthals lived in Europe, so they had to protect their bodies from frostbite and other cold-related problems. Although no frozen caveman clothing has ever been discovered, archaeologists think Neanderthals wore clothing to help maintain their core body temperature.

Circumstantial evidence of Neanderthal clothing includes a stone tool with residue from hide scraping, pointed bone awls used to punch holes in hides, and a twisted bit of cord, possibly from shoes or fabric.

The kind of clothing Neanderthals wore is still being debated, but it was likely more elaborate than a loincloth. If Neanderthals were wearing parkas, pants and boots, they were probably the first fashionistas, researchers told Live Science.

2. Neanderthals cared for their comrades with disabilities.

A fragment of a Neanderthal child's ear bone suggests she had Down syndrome and that she was cared for by her community. In a study published in June in the journal Science Advances, researchers identified a 6-year-old Neanderthal child nicknamed "Tina" in a cave in Spain. Tina's ear bone, which dated to between 273,000 and 146,000 years ago, has a shape associated with Down syndrome, as well as other abnormalities.

Although no genetic work has conclusively shown that Tina had Down syndrome, she nevertheless would have required care from her community to survive, according to the researchers, since her ear bone also suggested she had major hearing loss and vertigo. The finding suggests that other Neanderthals were helping her and her mother out of a sense of altruism.

3. Neanderthals created an early "glue factory."

As far back as 65,000 years ago, Neanderthals on the Iberian Peninsula were skilled engineers who made sticky tar in a precisely controlled environment. In the December issue of the journal Quaternary Science Reviews, researchers detailed their discovery of a hearth in a cave floor in Gibraltar. The hearth was full of charcoal and plant resin and was likely heated to 300 degrees Fahrenheit (150 degrees Celsius) to produce the gooey glue, which would have been used to fashion weapons such as spears.

The findings show Neanderthals were both very intelligent and able to collaborate to produce complex tools.

4. Modern humans and Neanderthals buried their dead differently.

Putting a dead body in a hole and covering it up is a burial practice exclusive to humans and Neanderthals. But Neanderthals buried their dead differently than Homo sapiens, according to research published this summer in the journal L'Anthropologie.

By looking at burials in Western Asia over a span of 85,000 years — when modern humans and Neanderthals overlapped — researchers noticed both similarities and differences. Everyone buried their dead without regard to their sex or age, and both modern humans and Neanderthals put items in their graves. But while Neanderthals buried their dead in a variety of positions in caves, early H. sapiens buried theirs in the fetal position outside caves.

Neanderthals and H. sapiens started burying their dead during the same time period — about 90,000 to 120,000 years ago — perhaps to mark their territory or lay claim to certain resources in a landscape teeming with hominins.

Related: From 'Lucy' to the 'Hobbits': The most famous fossils of human relatives

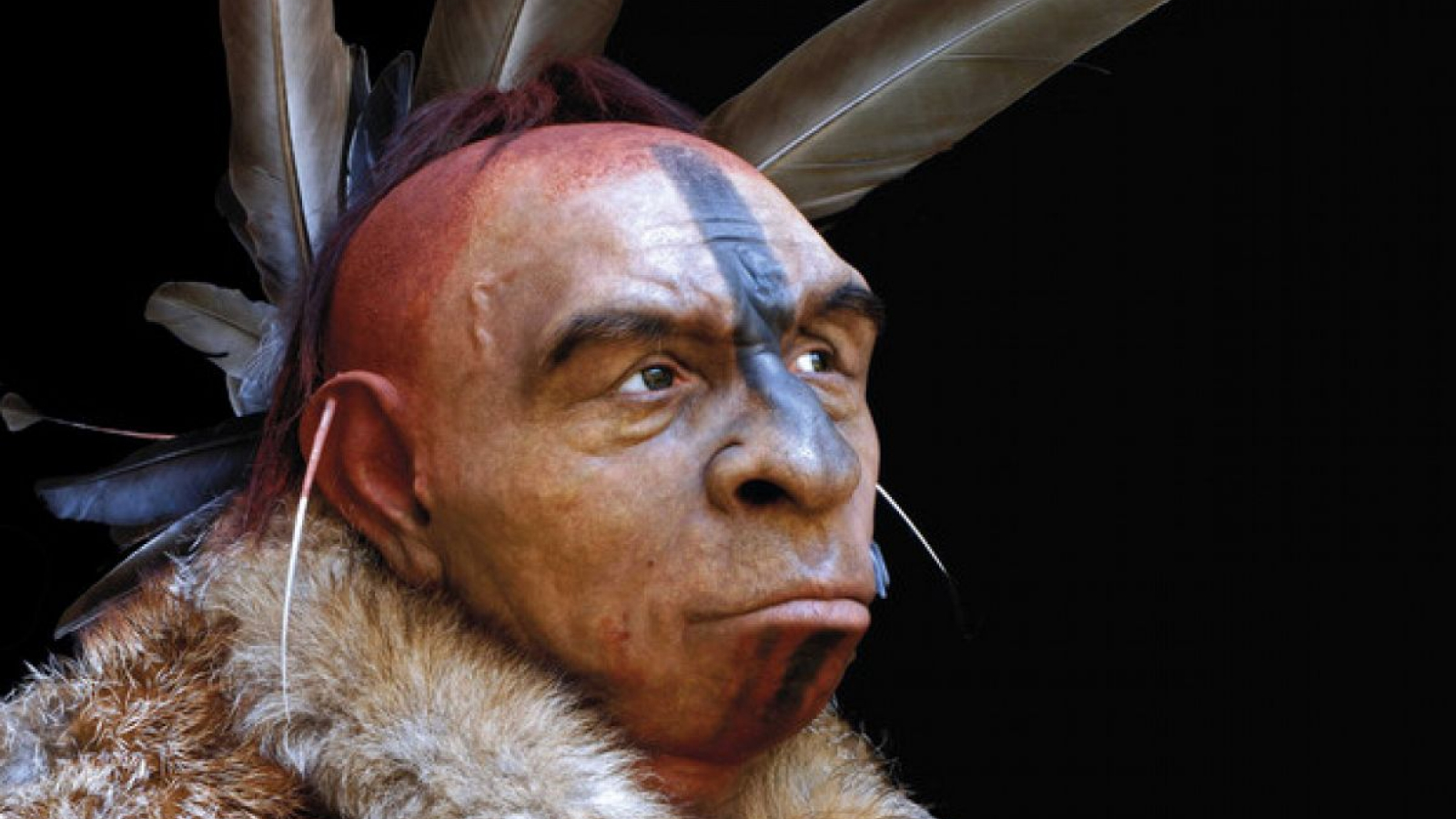

5. They looked a lot like us.

Numerous burials found in Shanidar Cave in Iraq provide some of the earliest evidence of purposeful interment of the dead. The skull of a woman known as Shanidar Z was pieced together from hundreds of fragments, and her face was reconstructed to provide a picture of one of our extinct relatives.

Neanderthal skulls look different from those of modern humans; they have huge brow ridges, prominent noses and no chin. But when muscles and skin are put back on the bone, even virtually, the similarities between Neanderthals and humans are apparent, and their long history of interbreeding is not surprising.

6. The last Neanderthals were isolated.

DNA sequencing of a Neanderthal nicknamed "Thorin" revealed that some groups may have been isolated for thousands of years before going extinct. Discovered in France's Rhône Valley, Thorin was dated to between 52,000 and 42,000 years ago. His DNA suggested that his lineage was quite inbred, even though other Neanderthal groups lived nearby.

"How can we imagine populations that lived for 50 millennia in isolation while they are only two weeks' walk from each other?" said Ludovic Slimak, a researcher at the Center for Anthropobiology and Genomics of Toulouse in France and lead author of the research. "Everything must be rewritten about the greatest extinction in humanity."

7. Male Neanderthal DNA seems to have vanished without a trace.

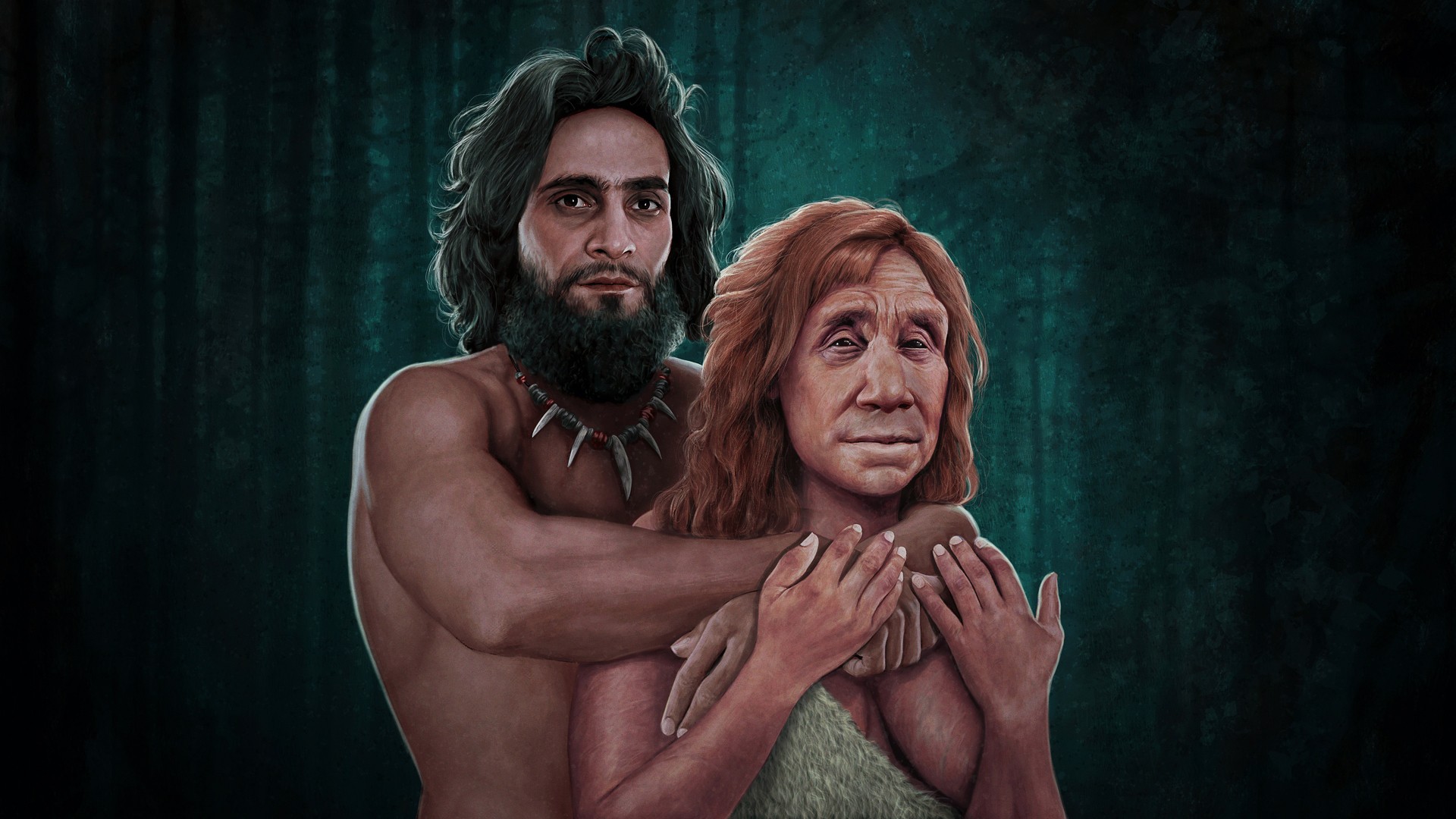

Although plenty of genes are shared between modern humans and Neanderthals, the H. sapiens genome does not have any Neanderthal Y chromosome DNA, which raises the question of how and why this genetic material vanished.

One intriguing possibility is that mating simply didn't work between Neanderthal males and H. sapiens women. Even though the two groups interbred several times over thousands of years, if a human mother was pregnant with a male Neanderthal baby, her immune system may have attacked the male fetus with unknown Y chromosome genes during pregnancy, resulting in a miscarriage. Eventually, if fewer male Neanderthal hybrid babies were born, the Y chromosome genes would disappear.

But it is not yet certain why the Neanderthal Y chromosome is no longer in our evolutionary gene pool. Because it is passed down only from father to son, it may have simply been lost over the generations.

8. Neanderthals were probably absorbed into modern-human groups.

Two key studies published recently showed that, although Neanderthals disappeared as a group, many of their genes did not.

By looking at more than 300 human genomes from the past 45,000 years, researchers estimated that most of the Neanderthal DNA that persists in us is from almost 7,000 years of interbreeding that began around 47,000 years ago.

Conversely, research published in July in the journal Science estimated that the Neanderthal genome may have been between 2.5% and 3.7% human, indicating that both human and Neanderthal populations had a long history of exchanging mates. The genetic analysis also revealed that the Neanderthal population size was quite small. The finding suggests that, rather than undergoing a dramatic extinction, the Neanderthals were simply absorbed into larger human groups.

9. Neanderthal DNA affects our health.

Ongoing DNA research also revealed that our health is affected by Neanderthal genes, for better or for worse.

Humans inherited Neanderthal genes for certain pregnancy hormones, which are associated with increased fertility and a lower risk of miscarriage. But other gene variants from our Neanderthal cousins make us more susceptible to allergies and Type 2 diabetes, more sensitive to pain and sunlight, and more likely to be at risk for nicotine addiction, severe COVID-19, autoimmune conditions and depression.

10. Humans probably did not kill off Neanderthals — at least, not directly.

We also learned that modern humans didn't purposely kill off the world's last Neanderthals. In addition to absorbing some of the Neanderthals through interbreeding and gene exchange, humans appear to have simply outcompeted Neanderthals by falling back on our vast social networks when times were tough and leaving our introverted cousins high and dry.

So who was the last Neanderthal? Although researchers still don't know for sure, current evidence points to southern Iberia as a potential location for Neanderthals' last stand around 37,000 years ago. After that time, Neanderthals as a distinct group ceased to exist, although they live on, in part, through the genes they shared with us.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Killgrove holds postgraduate degrees in anthropology and classical archaeology and was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.