10 things we learned about our human ancestors in 2023

Findings about our human ancestors continue to surprise us, especially those from 2023.

Humans are everywhere nowadays, but Homo sapiens and our close relatives weren't so widespread in the past. In fact, the ancestors of modern humans nearly went extinct just under 1 million years ago. And many lineages of human or close human relatives vanished without a trace; we have evidence of their existence only from discovering and studying their fossils.

Here's a look back at 10 major findings about humans and our close ancient relatives from 2023 and what they teach us about our own evolution.

Related: When did Homo sapiens first appear?

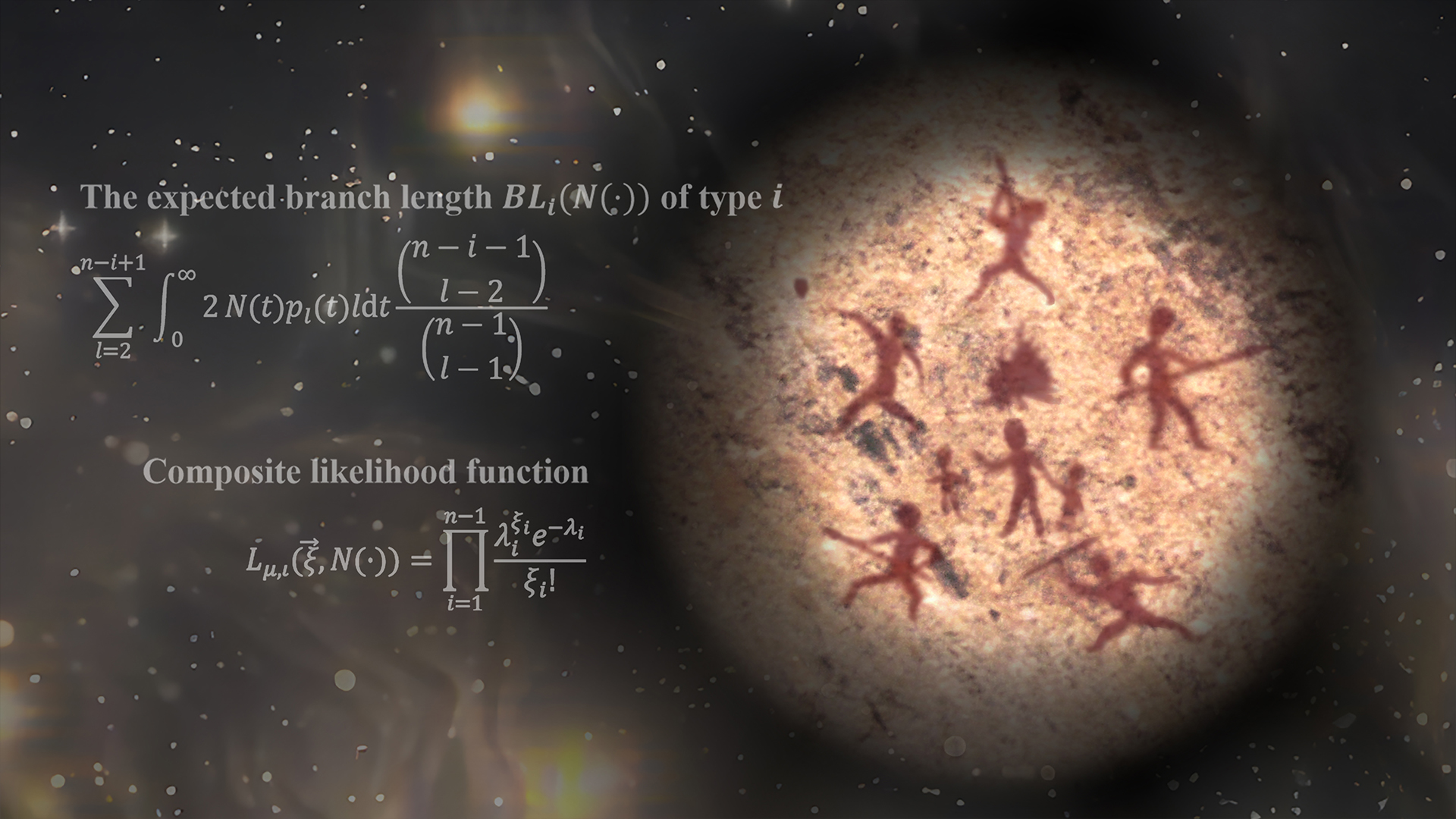

1. Ancestors of modern humans nearly went extinct

Nearly 1 million years ago, the ancestors of humans faced a "close call with extinction," according to a study in the journal Science. For more than 100,000 years, our numbers hovered at around 1,300 individuals, a minuscule number compared with our current population of 8.1 billion people.

Scientists uncovered humans' brush with extinction by looking at the genomes of more than 3,150 modern-day humans from both African and non-African populations. An analytical tool helped them investigate the diversity of today's genetic sequences and work backward to see what happened long ago.

They found that between 813,000 and 930,000 years ago, the ancestors of modern humans went through a severe "bottleneck" when they lost about 98.7% of their breeding population. Talk about a small dating pool!

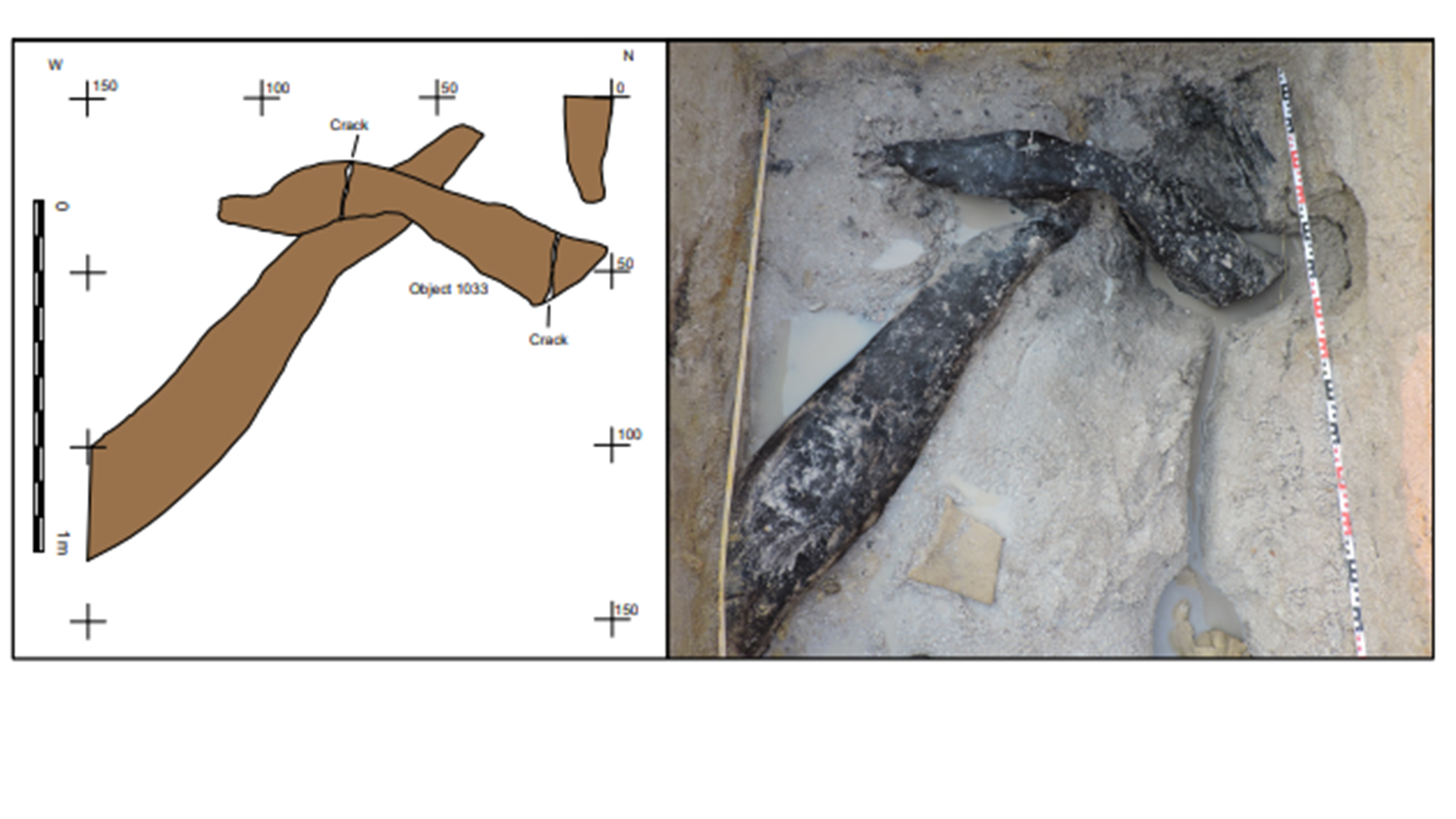

2. Human relatives crafted wood 476,000 years ago

Humans are clever, of course, but so were our ancient relatives. Archaeologists in Zambia found the oldest known wooden construction crafted by an ancient human relative — a 476,000-year-old structure that was notched like a Lincoln Log.

Of the findings, two were found with stone tools below the Kalambo River and three were covered in clay deposits above the river level, according to the study in the journal Nature.

The research shows that "humans and hominins used resources that were available to them," Shadreck Chirikure, a professor of archaeological science at the University of Oxford who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email.

3. 300,000-year-old jawbone comes from unknown lineage

Fragments of a 300,000-year-old jawbone may come from an unknown human lineage, according to a study in the Journal of Human Evolution. The jawbone, found in east-central China, belonged to a young teenager who had an unusual mosaic of ancient and modern characteristics.

In essence, this teen had a modern, human-like face, but their skull looked like that of the early Homo sapiens.

This complex set of traits suggests that the teen and other ancient individuals found at Hualongdong could be related to Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, Denisovans, or maybe even another lineage entirely.

4. Two distinct African groups gave rise to modern humans

Before modern humans came onto the scene at least 300,000 years ago, our ancestors consisted of two distinct but closely related groups that lived in Africa, a study in the journal Nature found. Although these two groups had split, people within them continued to mate with the "other group" over time.

For the study, the researchers investigated modern human genomes from southern, eastern and western Africa. The analysis revealed that Homo sapiens descended from two or more genetically distinct groups that continued to mingle over time. This split happened more than 120,000 years ago, but it's not entirely clear when.

The findings suggest our human ancestors didn't interbreed with now-extinct human relatives like Homo naledi, whose anatomy is different from ours. It also upends the idea that humans evolved from a single branch that broke off from our closest relatives.

5. Modern humans migrated to Europe in three waves

When, exactly, did modern humans enter Europe? They did so in three major waves: 54,000, 45,000 and 42,000 years ago, a study in the journal PLOS One found.

For years, researchers thought that 42,000 years ago marked humans' arrival into Europe. This date came from teeth unearthed in Italy and Bulgaria. But then, a 2022 study found evidence of modern humans in France dating to 54,000 years ago. Now, stone artifacts thought to be crafted by modern humans in Europe were dated to 45,000.

However, this three-wave model is far from confirmed. Future evidence may support or retract from the possible 45,000-year-old wave.

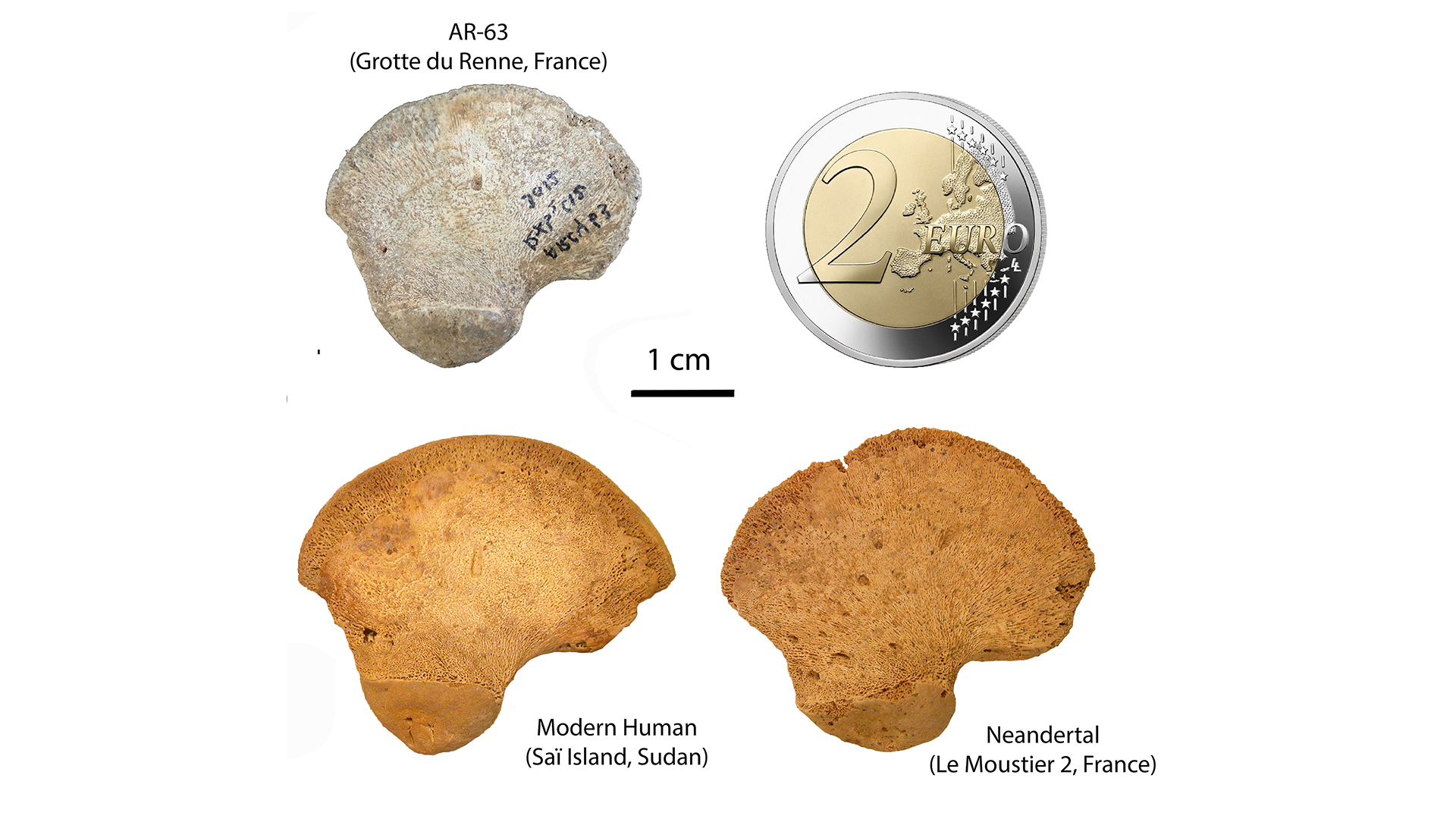

6. Tiny fossil is from 40,000-year-old mystery lineage

A tiny fossil hip bone unearthed in France surprised scientists when they realized it likely came from an early, previously unknown lineage of modern human, a study in the journal Scientific Reports found.

The 40,000-year-old bone — a newborn's hip bone, known as an ilium — is subtly different from those found in humans alive today. It's possible that the bone comes from a group of Neanderthals and humans that were living together, the researchers said.

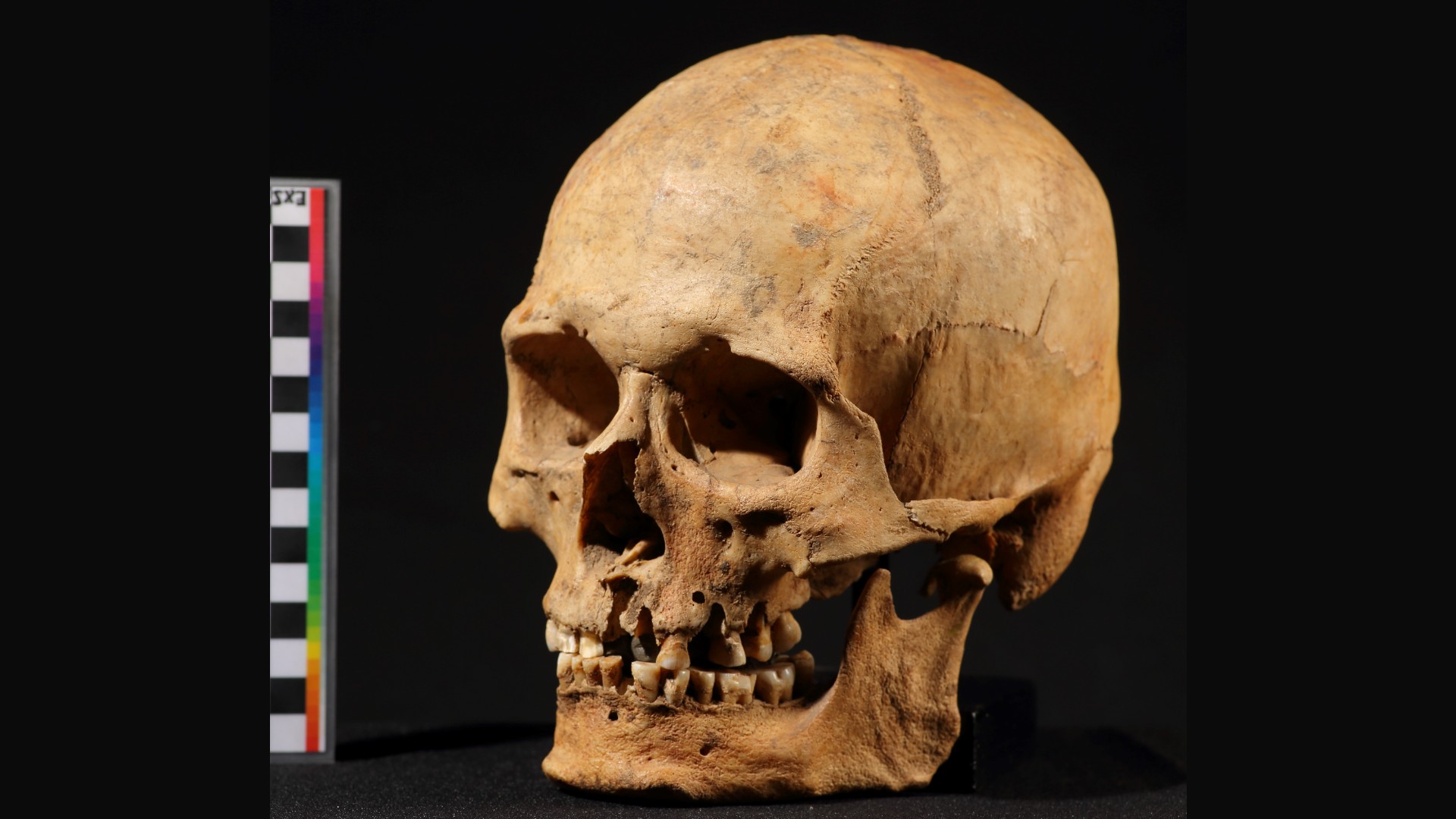

7. Europe's first permanent residents settled in Crimea

The first modern humans to set up shop in Europe settled in Crimea around 37,000 years ago, a study in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution found.

Researchers sequenced the DNA of two male skeletons that were radiocarbon-dated to about 35,800 to 37,500 years ago. This revealed that the descendants of these individuals gave rise to a people who carved Venus figures, stone tools and jewelry about 7,000 years later.

"Our study adds a fundamental piece to the jigsaw of the peopling of Europe by anatomically modern humans," study author Eva-Maria Geigl, research director at the Institute Jacques Monod in Paris, told Live Science in an email.

8. Unknown hunter-gatherer lineage discovered

The largest study to date on prehistoric European hunter-gatherer genomes has revealed a previously unknown lineage of European hunter-gatherers from the last ice age.

This mysterious lineage survived the coldest parts of the last ice age but vanished during a warm spell that began around 15,000 years ago, according to a study in the journal Nature.

The group, dubbed the Fournol, was known to have buried their dead in caves and sometimes may have ritually cut the bones after death, the researchers said.

9. The first Americans

Some of the first humans to venture into the Americas during the last ice age hailed from China, a DNA study in the journal Cell Reports found.

Parts of this ancient group appear to have migrated to Japan, too, clearing up a mystery of why there are similarities in the artifacts of Chinese, Indigenous American and Indigenous Japanese peoples.

The study "matches well with what we know about the archaeological record of Japan, and lends weight to current models of how humans came to populate the Americas," Loren Davis, an archaeologist at Oregon State University in Corvallis who was not involved with the research, told Live Science in an email.

10. Siberian population vanishes

A previously unknown group of hunter-gatherers that trekked through Siberia more than 10,000 years ago aren't with us anymore; they vanished, a study in the journal Current Biology found.

Genetic evidence of this mysterious group was found by analyzing the DNA of human remains from North Asia dating as far back as 7,500 years. The research also revealed that ice age humans went back and forth across the Bering Land Bridge between Asia and North America.

The team also examined the remains of a shaman from about 6,500 years ago who died more than 900 miles (1,500 kilometers) away from the group he had genetic ties to. In other words, ancient people got around, even in frozen places.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.