12,500-year-old rock art 'canvas' in the Amazon reveals early Americans' connection with wildlife

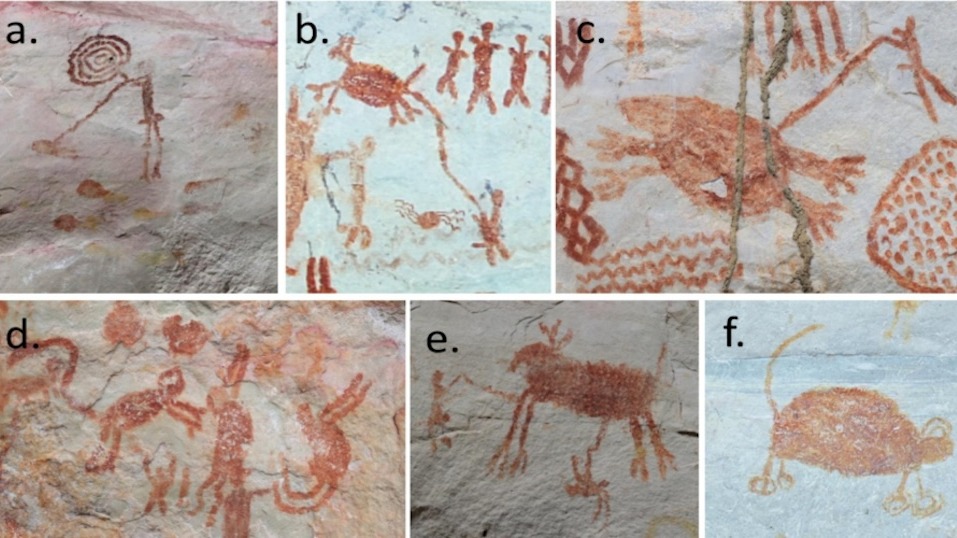

Thousands of ochre rock drawings, including images of humans and animals morphing into one another, offer a striking glimpse at early life in the Amazon.

A gallery of striking ochre paintings drawn onto massive rock faces offers insight into the close relationship between humans and animals living in the Amazon thousands of years ago.

The artwork is located on rocky outcroppings at Cerro Azul in Serranía de la Lindosa, a cliff in Colombia. It features 3,223 drawings of humans and animals, including a menagerie of fish, reptiles and mammals of various sizes, according to a new study in the September issue of the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology.

Some of the imagery even depicts animals and humans morphing into each other, indicating "the rich mythology that guided generations of indigenous Amazonians," according to a statement from the University of Exeter.

Although the researchers have not formally dated the canvas of art, they estimated that it has been around since 10500 B.C.

"These rock art sites include the earliest evidence of humans in western Amazonia, dating back 12,500 years," lead author Mark Robinson, an associate professor in the Department of Archaeology and History at the University of Exeter, said in the statement.

Related: 9,000-year-old rock art discovered among dinosaur footprints in Brazil

The team found at least 22 species of animals, including deer, birds, peccary, lizards, turtles and tapir. After comparing the animal drawings with ancient butchered animal bones found in nearby excavations, the archaeologists found that the proportional representation of drawings by species did not match the proportion of animal bones, indicating that the Indigenous people didn't just paint what they ate. The butchered bones included a diverse diet, including fish, mammals and reptiles, such as snakes and crocodiles.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The art is an amazing insight into how these first settlers understood their place in the world and how they formed relationships with animals," Robinson said. "The context demonstrates the complexity of Amazonian relationships with animals, both as a food source but also as revered beings, which had supernatural connections and demanded complex negotiations from ritual specialists."

Because the rock art is so extensive, the researchers opted to focus on six panels, including the 131-foot-long (40 meters) El Más Largo, which contains 1,000 drawings, and the much smaller 33-foot-long (10 m) panel known as Principal, which contains 244 images, according to the statement.

After cataloging the artwork, researchers found that 58% of the drawings were figurative, of which half were images of animals. They also noticed scenes depicting people fishing.

Researchers can only speculate about the purpose and significance of the rock art.

"Though we cannot be certain what meaning these images have, they certainly do offer greater nuance to our understanding of the power of myths in indigenous communities," study co-author José Iriarte, a professor of archaeology at the University of Exeter, said in the statement. "They are particularly revealing when it comes to more cosmological aspects of Amazonian life, such as what is considered taboo, where power resides, and how negotiations with the supernatural were conducted."

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.