130,000-year-old Neanderthal-carved bear bone is symbolic art, study argues

The carved bear bone is one of the earliest human-made artifacts with "symbolic culture" unearthed in Europe.

A nearly 130,000-year-old bear bone was deliberately marked with cuts and might be one of the oldest art pieces in Eurasia crafted by the Neanderthals, researchers say.

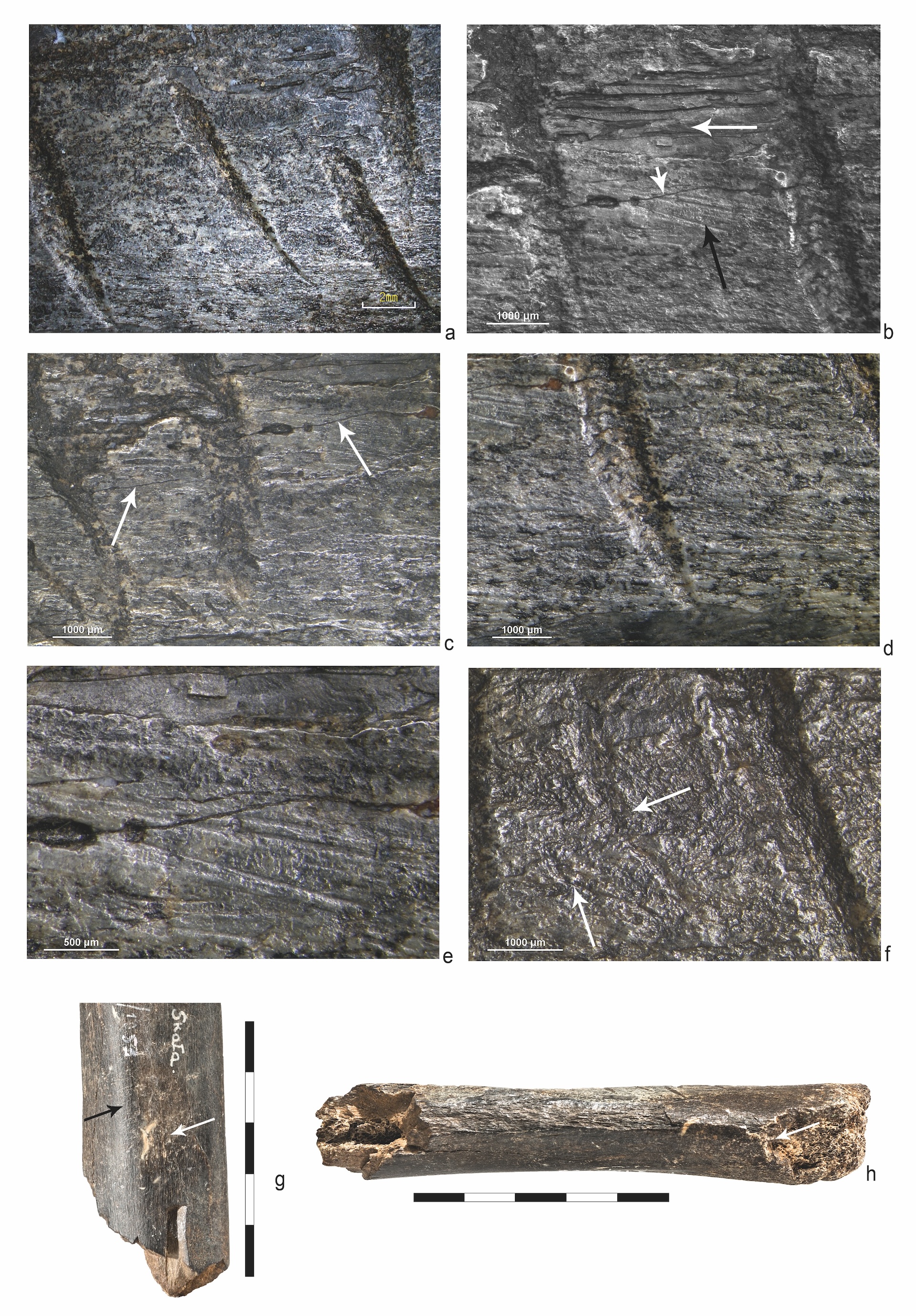

The roughly cylindrical bone, which is about 4 inches long (10.6 centimeters), is adorned with 17 irregularly spaced parallel cuts. A right-handed person most likely crafted the piece, probably in one sitting, a new study finds.

The carved bone is the oldest known symbolic art made by Neanderthals in Europe north of the Carpathian Mountains. It gives scientists a glimpse into the behavior, cognition and culture of modern humans' long-dead cousins, who lived in Eurasia from about 400,000 to 40,000 years ago, when they disappeared.

"It is one of the quite rare Neanderthal objects of symbolic nature," Tomasz Płonka, professor of archaeology at the University of Wrocław, told Live Science. "These incisions have no utilitarian reason." For instance, the bone does not appear to be a tool or an object of ritual importance, the study found.

Researchers discovered the bone in 1953 in Dziadowa Skała Cave in southern Poland and initially believed it was the rib of a bear. They excavated the bone from a layer dating to the Eemian period (130,000 to 115,000 years ago), one of the warmer periods of the last ice age. However, Płonka's team found that the bone is an arm bone (radius) that came from the left forelimb of a juvenile bear, most likely a brown bear (Ursus arctos).

Related: Antarctic ice hole the size of Switzerland keeps cracking open. Now scientists finally know why.

In the new study, the researchers examined the bone with a 3D microscope and computed tomography (CT) scans, which enabled them to make a digital model of the bone. Based on this model, the researchers suggested that the marks showed several characteristics of intentional organization. For instance, the marks were repetitive, meaning that the incisions were repeated in a similar fashion; similar, because they all belong to the same basic shape despite some size differences; limited, as the markings were confined to a specific area, even though there was room for more; and organized, as the cut marks were placed in a systematic way, even though their spacing varies slightly.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These consistencies suggest that the prehistoric artist wasn't just doodling and may have had advanced cognitive abilities, the researchers wrote in the study, which was published April 17 in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

To figure out how the incisions were made, the team made experimental marks on fresh cattle bones with replica flint blades and Middle Paleolithic knives using seven incision techniques, including to and fro movements and vigorous sawing movements.

The marks aren't consistent with butchering, tool use, or animal trampling, the team found. Moreover, they appear to be made intentionally, most likely in one sitting with a flint knife. A comparison of the incisions with experimental cut marks showed that almost all the incisions were made by quick, repeated knife movements toward the knife operator, according to the study.

"Most of the incisions have a very characteristic comma-like end that curves to the right. When our experimenter, who was a right-handed person, moved the flint instrument towards himself, the incisions curved to the right," Plonka explained. "Therefore, we know that the Neanderthal who made these incisions was a right-handed person."

It's possible the maker was trying to pass on some numerical message, Plonka suggested.

Paul Pettitt, a professor of archaeology who specializes in the European Middle and Upper Paleolithic at Durham University in the U.K, commended the study for confirming a long-held suspicion that the incisions made on this bear bone were cut carefully by a right-handed Neanderthal, rather than left accidentally by a carnivore gnawing on it.

Neanderthals had a peculiar habit of making similar parallel marks on bones that researchers now believe was some sort of symbolic culture. One of the most interesting examples is the cranium of a Neanderthal female with 35 mostly parallel carvings.

"That such series of parallel incisions really appear with the Neanderthals and not before, suggests that they were a cultural practice that had meaning and function, and not, say, the product of unconscious personal habits like modern doodling," Pettitt, who was not involved with the study, told Live Science in an email.

"It is remarkably difficult — and controversial — to try to ascertain the specific information recorded by such 'symbolic' marks," he added. Even so, "the Dziadowa Skala Cave incised bone at the very least shows us that Neanderthals were using visual culture to encode information, a truly human capability," Pettitt said.

Soumya Sagar holds a degree in medicine and used to do research in neurosurgery at the University of California, San Francisco. His work has appeared in New Scientist, Science, Discover, and Mental Floss. He is a passionate science writer and a voracious consumer of knowledge, especially trivia. He enjoys writing about medicine, animals, archaeology, climate change, and history. Animals have a special place in his heart. He also loves quizzing, visiting historical sites, reading Victorian literature and watching noir movies.