1,500-year-old burial of lynx with 4 dogs stacked on it puzzles archaeologists

Archaeologists aren't sure why a lynx and four dogs were buried together in Hungary around 1,500 years ago.

The discovery of a lynx buried with four dogs at an early-medieval settlement in Hungary is confounding archaeologists, as these wild cats are rarely found in archaeological digs.

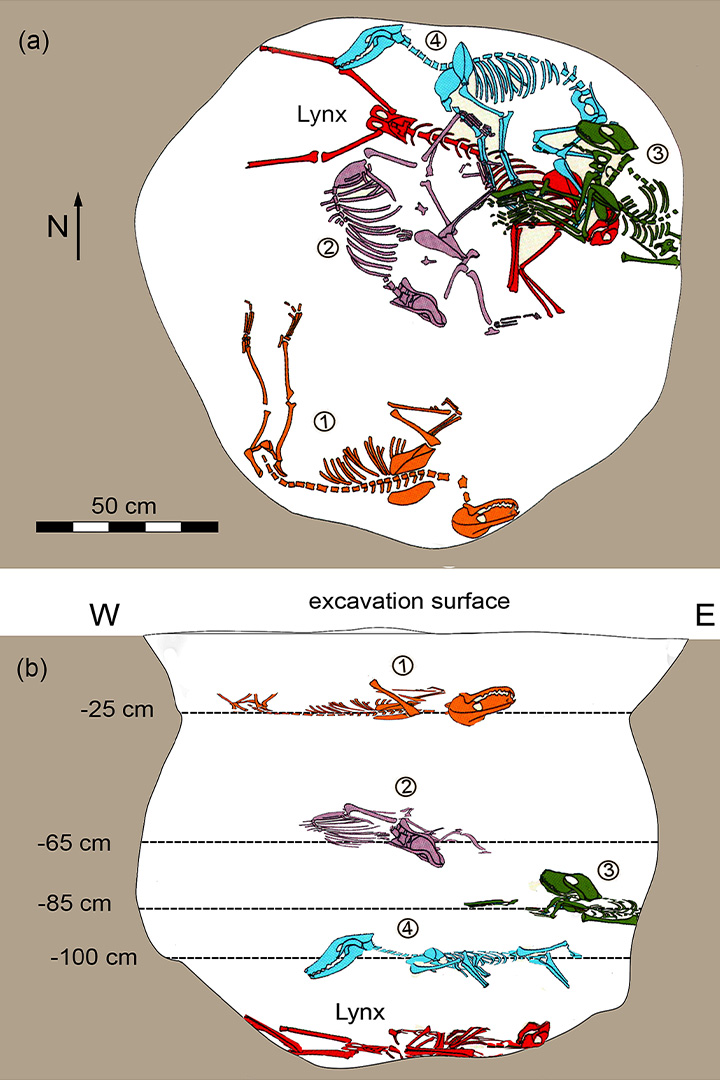

The fifth-to-sixth-century pit, which was about 4.6 feet (1.4 meters) deep, contained a complete lynx skeleton at the bottom and the skeletons of four dogs — the size of present-day pointers or German shepherds — layered on top of it. Possible interpretations of the unique find, such as a hunting accident and a lynx cult, are detailed in a new study published March 21 in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology.

Found all over the Northern Hemisphere, the lynx — better known as a bobcat in North America — is a large carnivore that typically preys on small mammals and birds. While the Eurasian lynx has all but disappeared in continental Europe due to human encroachment on their forest habitats, the species was widespread before modern times.

Yet remains of lynxes have been found at only a couple dozen archaeological sites in Europe and Asia. "Archaeologically, lynx skeletons are extremely rare, as lynx meat is usually not consumed," study co-author Lászlo Bartosiewicz, an archaeologist at Stockholm University, told Live Science in an email. Sometimes, lynx claws end up in human graves, likely because their pelts were buried there and decayed, Bartosiewicz said, but intact skeletons are rarely encountered.

Related: Ancient Romans sacrificed birds to the goddess Isis, burnt bones in Pompeii reveal

The pit of animals was found at the site of Zamárdi-Kútvölgyi-dűlő in west-central Hungary, an area known as Pannonia under Roman rule. The last phase of occupation of the site dates to the early Middle Ages, not long after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Zamárdi appears to have been a small settlement at that time, and archaeologists have previously discovered dozens of buildings, pits, wells and ovens there. The people likely obtained their food from domesticated animals and crops rather than from hunted wild game.

At the bottom of the beehive-shaped pit, the male lynx skeleton was found fully stretched out. Four adult dogs — two females and two males — were buried on their right sides, above the lynx; each animal was separated by an 8-to-16-inch (20 to 40 centimeters) layer of dirt.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It is hard to summarize our interpretation of the lynx/dogs burial as no parallels (archaeological or ethnographic) are known," Bartosiewicz said.

It's possible that the burial is the end result of a deadly confrontation, in which the dogs may have been killed by a cornered lynx, the researchers said. Or, perhaps it was a purposeful animal burial with ritual significance. But if this were the case, the researchers noted in their study, it's surprising that more care wasn't taken in the placement of the lynx and dogs.

"Unfortunately, the Migration Period population of a former Roman province may have represented almost any ideology given the chaotic history of the period," Bartosiewicz said.

Victoria Moses, a zooarchaeologist at Harvard University who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email that "the authors are wise not to over-interpret what burying lynx and dogs meant to the inhabitants of the site at the time." But given the presence of such a unique animal in an atypical burial made within a short time frame, "the likelihood of ritual is high," Moses said.

Given the dynamic multicultural setting of Zamárdi, it is currently impossible to make an unambiguous interpretation of the animal pit without further evidence, the researchers concluded.

In the absence of additional written or ethnographic material on the perception of this large carnivore in the early Middle Ages, "our rather special find is indeed the 'missing lynx' in this story," Bartosiewicz said.

Editor's note: Updated at 1:18 p.m. on April 9 to note that the dogs would have been the size of a modern pointer or German shepherd and that while lynx pelts don't preserve in ancient burials, their claws often do.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus