1,500-year-old DNA used to reveal likeness of Chinese Emperor Wu

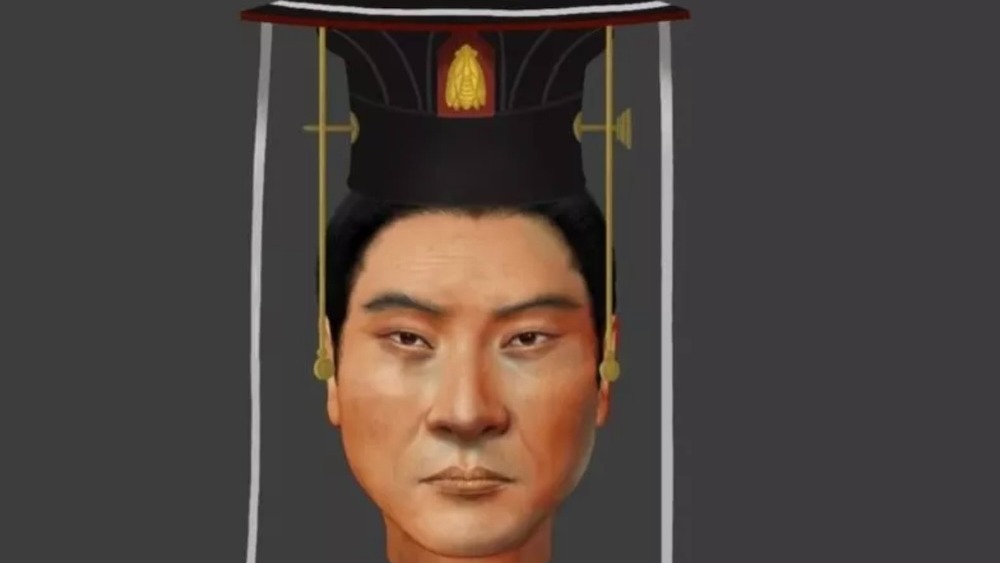

Scientists used DNA to create a facial reconstruction of a Chinese emperor who ruled 1,500 years ago.

DNA from the remains of a Chinese emperor who lived 1,500 years ago has helped scientists create a facial approximation and learn what may have caused his death, a new study finds.

Emperor Wu ruled China's Northern Zhou dynasty from A.D. 560 until his death in 578, at the age of 36, according to a study published Wednesday (March 28) in the journal Current Biology.

Wu is perhaps best known for building a strong military presence, pacifying the Turks and unifying northern China after defeating the Northern Qi dynasty, the new study reported.

However, what caused the emperor to die at such a young age has long been a matter of debate, with some historians wondering if he was poisoned by rivals and others purporting that he died of an unknown illness. This new DNA analysis confirms that he likely died due to complications from a stroke, according to a statement.

Archaeologists originally discovered Wu's tomb in 1996. It contained the ruler's skeleton including a "nearly complete skull," from which researchers were able to extract his DNA to perform a genetic analysis, according to the statement.

Related: Lavish, 800-year-old tombs in China may hold remains of Great Jin dynasty elites

"Our work brought historical figures to life," study co-author Pianpian Wei, an assistant professor in the Department of Cultural Heritage and Museology at Fudan University in Shanghai, said in the statement. "Previously, people had to rely on historical records or murals to picture what ancient people looked like. We are able to reveal the appearance of the Xianbei people directly."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

That image is of a man with brown eyes, black hair and a darker complexion, which is similar to present-day Northern and Eastern Asians. The study also confirmed that Wu was ethnically Xianbei, a nomadic group that lived in what is now Mongolia and northern parts of China, according to the statement. The DNA analysis revealed that the Xianbei people migrated south into northern China, and coupled with people who were ethnically Han Chinese.

"This is an important piece of information for understanding how ancient people spread in Eurasia and how they integrated with local people," study co-author Shaoqing Wen, a doctoral student of archaeological science at Fudan University, said in the statement.

The new analysis concurs with historical records that described Wu as having "aphasia [an inability to understand or express speech due to brain damage], drooping eyelids, and an abnormal gait — potential symptoms of a stroke," according to the statement.

"Some scholars said the Xianbei had 'exotic' looks, such as thick beard, high nose bridge and yellow hair," Wen said in the statement. "Our analysis shows Emperor Wu had typical East or Northeast Asian facial characteristics."

Researchers plan to continue their analysis by studying the people who once lived in Chang'an, an ancient city in northwestern China. The settlement served as the capital for Chinese emperors for thousands of years and was the eastern end of the Silk Road, a pivotal trade route that existed from the second century B.C. to the 15th century, according to the statement.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.