17th-century pirate 'corsair' shipwreck discovered off Morocco's Barbary Coast

The wreck is the first time the remains of a pirate corsair have been found "in the Barbary heartland."

Wreck-hunters have discovered the remains of a small 17th-century pirate ship, known as a Barbary corsair, in deep water between Spain and Morocco.

The wreck is "the first Algiers corsair found in the Barbary heartland," maritime archaeologist Sean Kingsley, the editor-in-chief of Wreckwatch magazine and a researcher on the find, told Live Science.

The vessel was heavily armed and may have been heading to the Spanish coast to capture and enslave people when it sank, its discoverers said.

But it was carrying a cargo of pots and pans made in the North African city of Algiers, probably so that it could masquerade as a trading vessel.

Florida-based company Odyssey Marine Exploration (OME) located the shipwreck in 2005 during a search for the remains of the 80-gun English warship HMS Sussex, which was lost in the area in 1694.

"As so often happens in searching for a specific shipwreck we found a lot of sites never seen before," Greg Stemm, the founder of OME and the expedition leader, told Live Science in an email.

Related: 10 of the most notorious pirates in history

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The 2005 expedition also found the wrecks of ancient Roman and Phoenician ships in the area, Stemm said.

News of the corsair wreck is only being released now, in a new article by Stemm in Wreckwatch, after extensive historical research.

Dread pirates

The Barbary corsair pirates were predominantly Muslims who began operating in the 15th century out of Algiers, which was then part of the Ottoman empire.

Much of the western coastline of North Africa, from modern-day Morocco to Libya, was known as the "Barbary Coast" at the time — a name derived from the Berber people who lived there; and its pirates were a major threat for more than 200 years, preying on ships and conducting slave raids along the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts of Europe.

The people captured in the slave raids were held for ransom or sold into the North African slave trade that operated in some Muslim countries until the early 20th century.

But the piratical activities of the Barbary corsairs came to an end in the early 19th century, when the pirates were defeated in the Barbary Wars by the United States, Sweden and the Norman Kingdom of Sicily in southern Italy.

Sunken ship

The corsair wreck lies on the seafloor in the Strait of Gibraltar, at a depth of about 2,700 feet (830 meters).

The ship was about 45 feet (14 m) long, and research indicates it was a tartane — a small ship with triangular lateen sails on two masts that could also be propelled by oars.

Tartanes were used by Barbary pirates in the 17th and 18th centuries, in part because they were often mistaken for fishing vessels, meaning other ships wouldn't suspect pirates were onboard, Kingsley said.

"I've seen tartanes described as 'low-level pirate ships,' which I like,” Kingsley said.

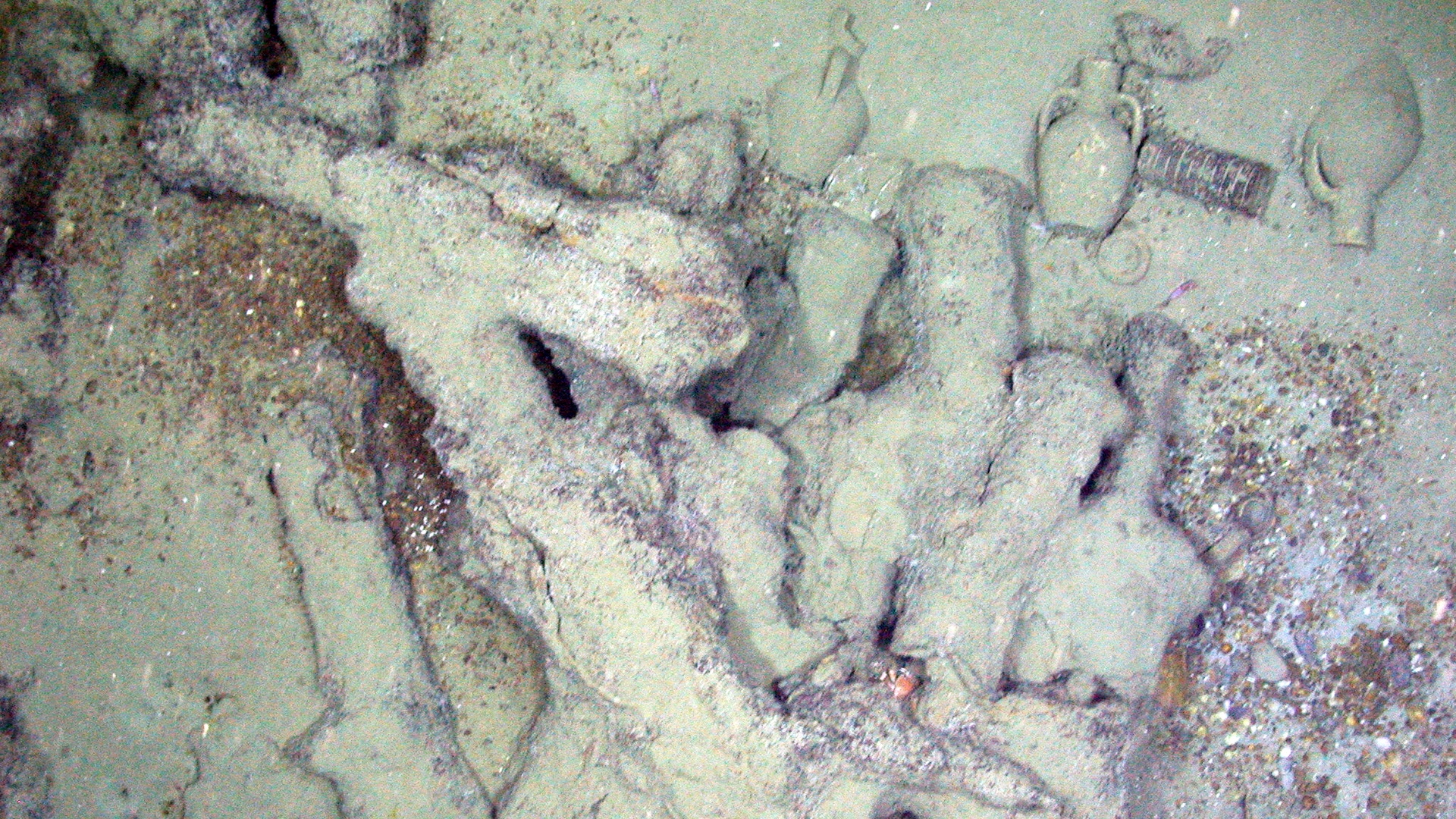

The wreck hunters explored the sunken corsair using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV), which revealed the vessel was armed with four large cannons, 10 swivel guns and many muskets for its crew of about 20 pirates.

"The wreck neatly fits the profile of a Barbary corsair in location and character," Kingsley said. "The seas around the Straits of Gibraltar were the pirates' favorite hunting grounds, where a third of all corsair prizes were taken."

Stemm added that the wrecked ship was also equipped with a very rare "spyglass" — an early type of telescope that was revolutionary at the time and had probably been captured from a European ship.

Other artifacts of the wreck support the notion this was a pirate ship laden with stolen goods.

"Throw into the sunken mix a collection of glass liquor bottles made in Belgium or Germany, and tea bowls made in Ottoman Turkey, and the wreck looks highly suspicious," he said. "This was no normal North African coastal trader."

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.