2,200-year-old grave in China contains 'Red Princess of the Silk Road' whose teeth were painted with a toxic substance

Archaeologists in China have discovered a unique burial of a woman whose teeth had been painted with cinnabar, with a toxic red substance that contains mercury.

In a first-of-its-kind discovery, archaeologists in China have unearthed the 2,200-year-old burial of a woman whose teeth had been painted with cinnabar, a toxic red substance.

Cinnabar is a bright-red mineral that's made of mercury and sulfur. Although it's been used since at least the ninth millennium B.C. in religious ceremonies, art, body paint and writing, this is the first time it's been found on human teeth, according to a study published Feb. 24 in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.

"This is the first and only known case of cinnabar being used to stain teeth in antiquity and throughout the world," study senior author Qian Wang, a professor of biomedical sciences at the Texas A&M University College of Dentistry, told Live Science in an email.

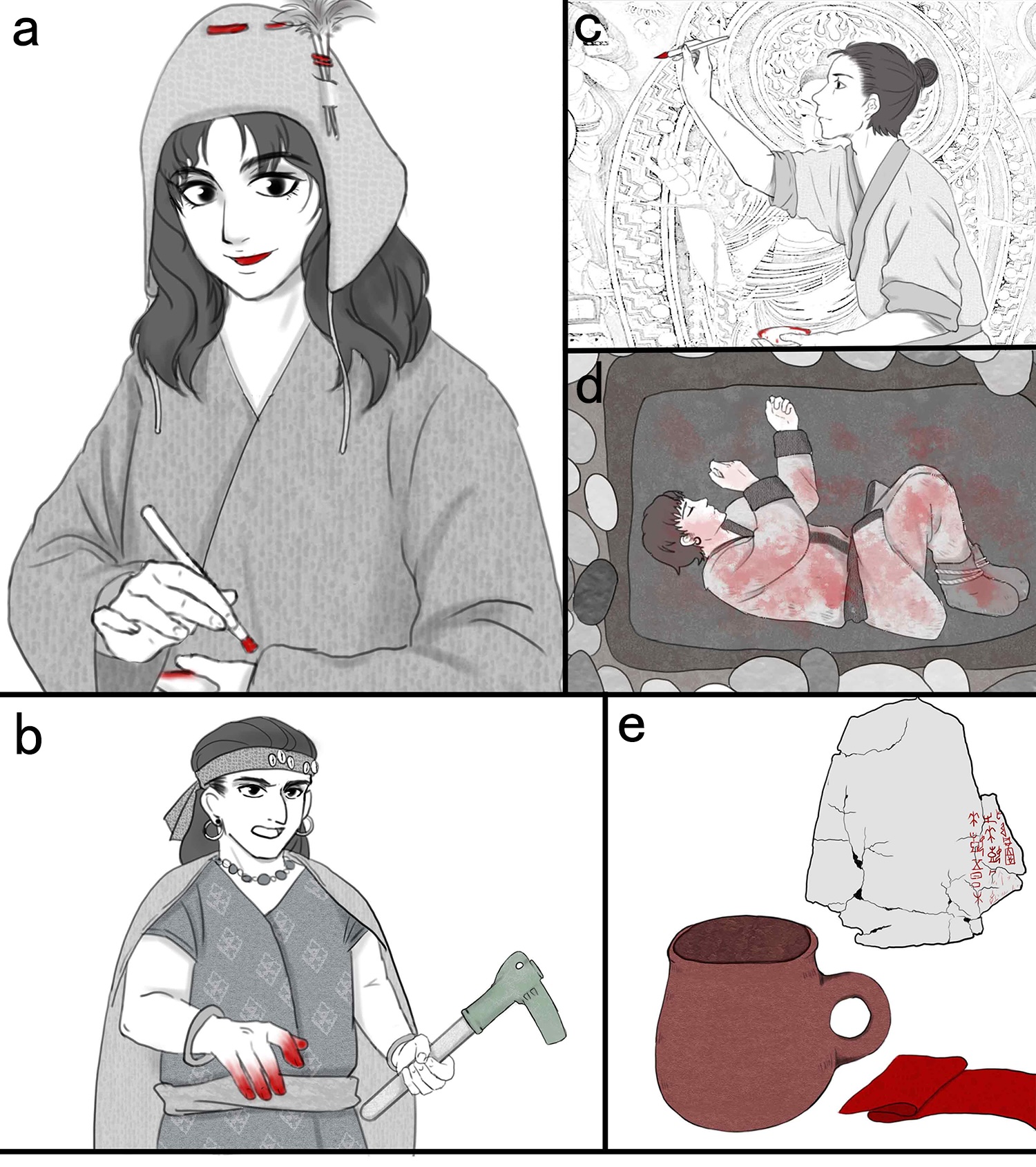

Archaeologists found the unusual remains while excavating a cemetery in Turpan City, in the Xinjiang region of northwestern China. Based on the cultural objects found in various graves, the archaeologists concluded that the deceased were Gushi people, who followed the Subeixi culture. The Subeixi culture, a horse riding pastoralist culture in which women rode horses using saddles, flourished in the Turpan basin nearly 3,000 years ago.

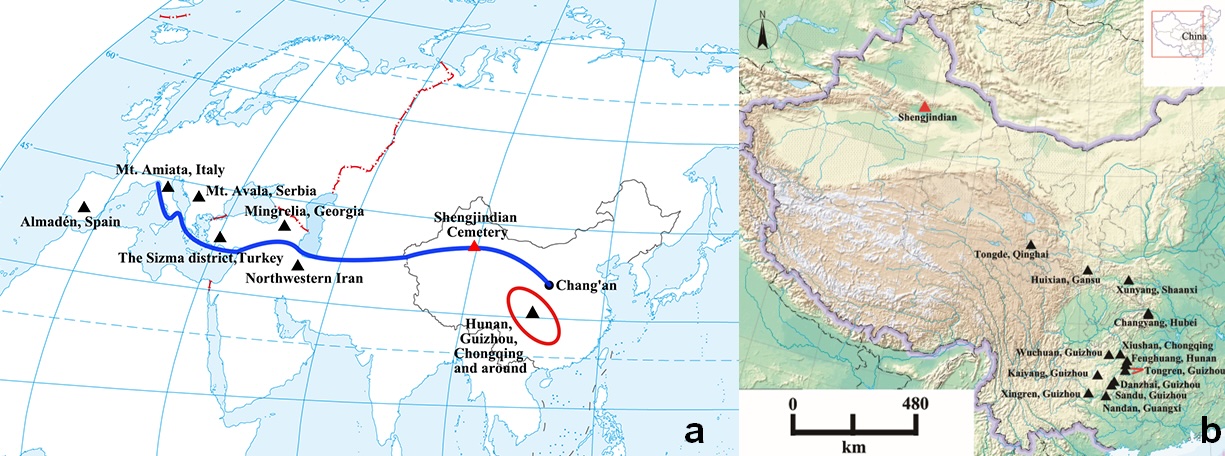

The cemetery lay on the main route of the Silk Road. The site was dated to 2,200 to 2,050 years ago via radiocarbon dating, putting it in the time frame when the Silk Road was active with the trade of precious goods, including cinnabar.

Related: Earliest evidence of mercury poisoning in humans found in 5,000-year-old bones

One of the graves in the cemetery held the remains of four individuals, including a juvenile. However, one adult skeleton in the burial stood out because its teeth had traces of red pigment. An anatomical analysis revealed that this individual was female and had died between the ages of 20 and 25. Intrigued, researchers scraped off a sample of the red pigment and studied it with three different spectroscopy methods, which can reveal the makeup of chemicals in a sample.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The analysis revealed that the pigment was cinnabar, which had been mixed with an animal protein, perhaps egg yolk or egg white, so it could be painted on the woman's teeth.

The team nicknamed the woman the "Red Princess of the Silk Road" after the "Red Queen," a female Maya aristocrat from seventh-century Mexico whose corpse was found covered in cinnabar powder inside a limestone sarcophagus.

Red Princess of the Silk Road

The Red Princess's teeth are an anomaly, as the Xinjiang region is not a source of cinnabar. However, it was mined and traded along the Silk Road in antiquity, the researchers noted. China and Europe, the beginning and end of the Silk Road, were the two most significant cinnabar-producing areas along this trade route. So it's possible that the cinnabar from the Turpan cemetery came from Europe, West Asia or other areas within China, such as the southwest, which was historically mined for cinnabar.

Although it's unknown why the woman's teeth were painted red, Wang said it could be "related to cosmetic enhancements, social status, or shamanism, or some kind of combination." Other mummies with facial paintings and tattoos have been found in the region and even the newly excavated cemetery, he noted. So it's possible that the Red Princess had facial painting or tattoos, distinct hairstyles, head dressing and costumes to go with her red teeth, Wang said.

Study co-author Li Sun, a professor of geology at Collin College in Texas, emphasized the dangerous nature of cinnabar application. She pointed out that during the whole process, from the preparation of the red pigment to its application (probably multiple times) inside the mouth, the red-toothed woman and her helpers might have inhaled fine particles of cinnabar or mercury vapors. Inhaling these substances is associated with harmful neurological effects such as headaches, insomnia, tremors, and cognitive and motor dysfunction, according to the World Health Organization.

Surprisingly, Wang and his team didn't find any evidence of mercury poisoning in her bones even though there's circumstantial evidence that it was applied repeatedly during her lifetime. "No traces of mercury were detected in her mandible, ribs and femur," Wang said. "Perhaps it was not [on her teeth] long enough to allow the toxin to be concentrated to a detectable level."

Soumya Sagar holds a degree in medicine and used to do research in neurosurgery at the University of California, San Francisco. His work has appeared in New Scientist, Science, Discover, and Mental Floss. He is a passionate science writer and a voracious consumer of knowledge, especially trivia. He enjoys writing about medicine, animals, archaeology, climate change, and history. Animals have a special place in his heart. He also loves quizzing, visiting historical sites, reading Victorian literature and watching noir movies.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.