2,600-year-old Celtic wooden burial chamber of 'outstanding scientific importance' uncovered by archaeologists in Germany

The discovery of an impeccably preserved Celtic burial chamber in southern Germany is a "stroke of luck for archaeology," scientists say.

Archaeologists in Germany have discovered an impeccably preserved wooden burial chamber at the center of an enormous burial mound from the early Celtic period.

The 2,600-year-old grave, uncovered near the town of Riedlingen, is only the second well-preserved Celtic burial chamber to be uncovered in Germany. Wood buried underground in dry or normal conditions usually decomposes within decades, at most. This makes such discoveries rare, prompting experts to call this Celtic burial a finding of "outstanding scientific importance," according to a translated statement from the local government.

"The Riedlingen grave is a stroke of luck for archaeology," Dirk Krausse, the state archaeologist of Baden-Württemberg, said during a news conference, according to the statement.

The ancient Celts lived in continental Europe to as far east as modern-day Turkey and included different groups, including the Gauls of what is now France and the Celtiberians in the Iberian Peninsula. Their original home territories are thought to have included parts of France, the Czech Republic and southern Germany, where this tomb was found.

The large chamber was around 11 feet wide by 13 feet long (3.4 by 4 meters). Its floors, walls and ceiling were constructed out of massive oak timbers that were exceptionally preserved thanks to damp conditions from groundwater and aquifers. This would have protected the wood from exposure to oxygen, which leads to decay.

Related: Possible 'mega' fort found in Wales hints at tension between Romans and Celtics

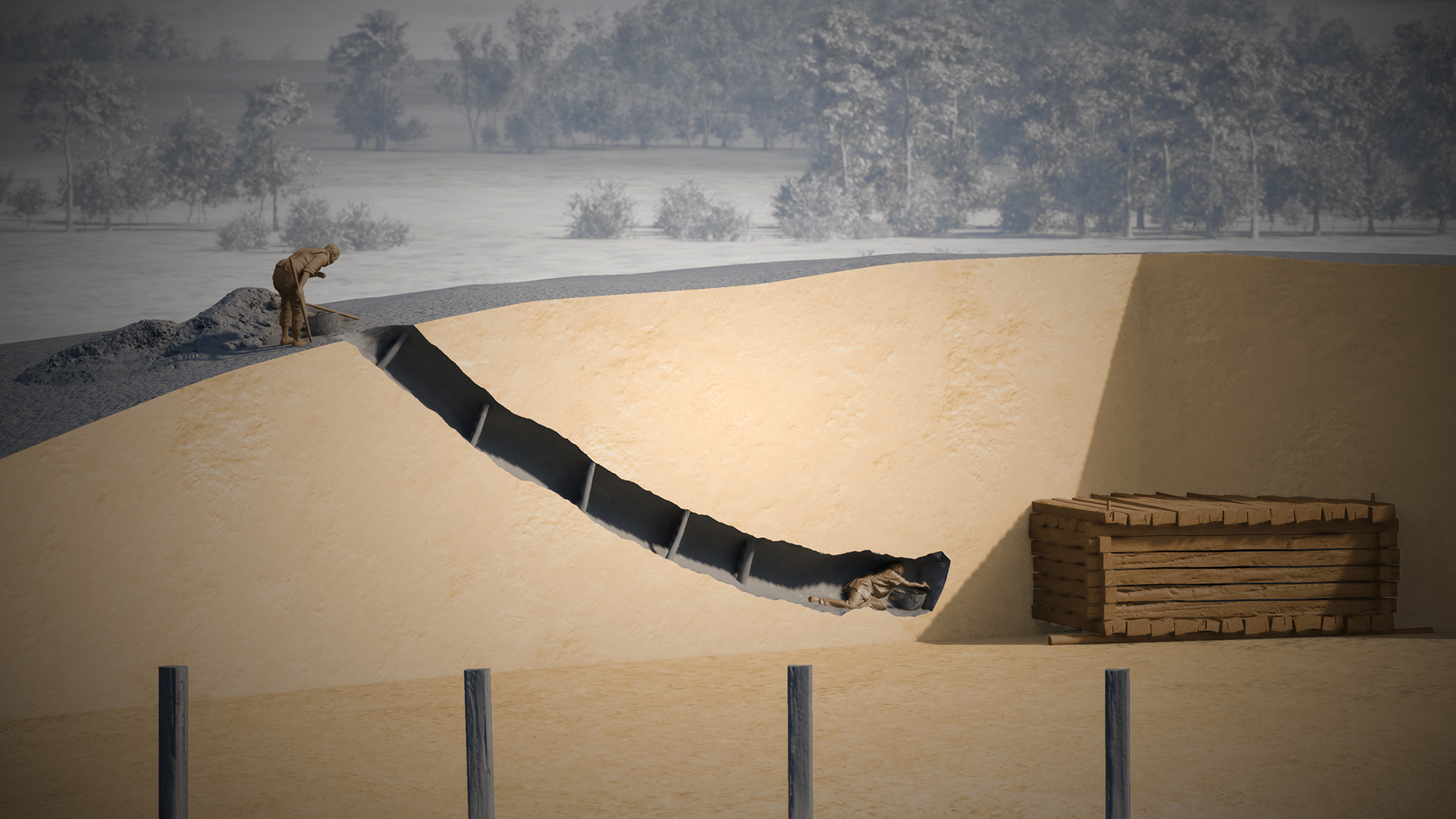

The chamber was uncovered at the center of a huge burial mound with a diameter of 213 feet (65 m) and a height of almost 20 feet (6 m). Its size led archaeologists to identify the entire complex as one of the few princely burial mounds that the Celts in southwestern Germany built for elite individuals between 620 and 450 B.C.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The preserved wood will allow archaeologists to use tree-ring dating to determine the exact year of the chamber. So far, they have dated the wood of what may be a tool left by Celtic builders to 585 B.C. This, among other observations, has led the archaeologists to hypothesize that the burial chamber was also built that year.

Despite its sturdy structure, ancient looters were able to infiltrate it. An excavation revealed that grave robbers had built two tunnels in the burial mound and created an entrance hole in the chamber's ceiling, which may explain the lack of valuable grave goods within the tomb. The team also discovered a number of nails in one of the looters' tunnels. They may have come from a four-wheeled chariot buried with the deceased — a custom that has been noted in other princely Celtic graves.

The team uncovered human remains in three locations. There were bones within the chamber; bones in a second, likely later grave closer to the burial mound's surface; and cremated remains in two older urns dating to around 600 B.C. buried beneath the burial mound.

The individual in the chamber was a young male who died between the ages of 15 and 20 years old and stood between 5 feet, 3 inches and 5 feet, 6 inches (160 to 168 centimeters) tall, a bone analysis found. The individual in the shallower grave was a slightly older male between the ages of 25 and 35.

Excavation of the site and analysis of the human remains are ongoing, the team said.

Margherita is a trilingual freelance writer specializing in science and history writing with a particular interest in archaeology, palaeontology, astronomy and human behavior. She earned her BA from Boston College in English literature, ancient history and French, and her journalism MA from L'École Du Journalisme de Nice in International New Media Journalism. In addition to Live Science, her bylines include Smithsonian Magazine, Discovery Magazine, BBC Travel, Atlas Obscura and more.