3,000-year-old 'bear' bone from Alaska isn't what it seems

A bone found in a cave in Alaska and thought to from a bear is actually from a human, casting new light on the genetics of Native American peoples.

A 3,000-year-old bone unearthed from a cave in southeastern Alaska is not from a bear, as originally thought, but from one of our own — a woman. And new research reveals that her genetics are essentially the same as the Native American people who live in the region now.

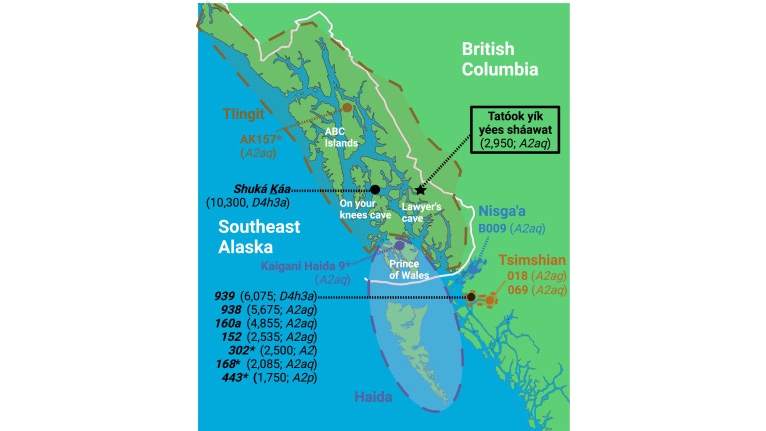

The 1.2-inch-long (3 centimeters) bone fragment was discovered in the 1990s in Lawyer's Cave on the Alaskan mainland, east of Wrangell Island in the Alexander Archipelago.

It was found near shell beads and a bone awl, which indicated that the cave was inhabited by prehistoric humans at some point. But scientists thought the bone was from an animal — perhaps a bear — that had been hunted by Native Americans at that time.

The bone fragment seems to have been kept in an archive until 2019, when it arrived in a laboratory at the University at Buffalo in New York. Once there, genetic tests showed that the bone once thought to be from a prehistoric bear was actually from a prehistoric human.

"I was very excited," Alber Aqil, a doctoral student of biological sciences at the University at Buffalo who made the discovery, told Live Science. "I had just come to the department, and this was my first project."

Related: 10 amazing things we learned about our human ancestors in 2022

Ancient human

Research on the fragment revealed it is part of the humerus, or upper arm bone, of a Native American woman who lived about 3,000 years ago. After consulting local tribal authorities, Aqil and his colleagues dubbed the woman "Tatóok yík yées sháawat" in the Tlingit language, or "young lady in cave," according to the study, published in the May issue of the journal iScience.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Only about 15% of the prehistoric woman's genome could be extracted from the bone, Aqil said; but it was enough to determine that the genetics of Tatóok yík yées sháawat are the same as the Tlingit people and related Native American peoples who still live in the region today.

"I would say that the Tlingit people have been where they are for a [very] long time," he said.

Prehistoric migrations

Aqil explained that scientists now believe Native Americans entered North America from Siberia in three waves. The first, of all non-Inuit Indigenous people, occurred about 23,000 years ago over the Beringia Land Bridge. A second wave, via the sea about 6,000 years ago, saw the Paleo-Inuit peoples arrive in the region: and possibly a third wave, again by sea, occurred between about 2,000 and 1,000 years ago, when the Neo-Inuit peoples arrived.

The genetics of "young lady in cave," however, are not seen in ancient DNA from the Paleo-Inuit people; and so it seems "Tatóok yík yées sháawat" — or TYYS, as she's now known for short — was a descendant of people who came in the first wave, he said.

Neither the TYYS genome nor the handful of other ancient Alaskan human genomes show any sign that the people in the first migration interbred with Paleo-Inuits at any time: "It has been claimed before that there was interbreeding between people in the first two waves, but we could not find any evidence for it," Aqil said.

The next stage of the project would be to return the bone fragment to representatives of the Indigenous peoples of southeastern Alaska, so that it could be reburied as a fragment of an ancestor with appropriate ceremonies, he said.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.