47,000 years of Aboriginal history destroyed in mining blast in Australia

Humans used the now-destroyed rockshelter throughout the last ice age until just a few decades ago.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains an image of deceased people, which is used with permission from the Traditional Owners.

In May 2020, as part of a legally permitted expansion of an iron ore mine, Rio Tinto destroyed an ancient rockshelter at Juukan Gorge in Puutu Kunti Kurrama Country in the Pilbara region of Western Australia.

Working with the Traditional Owners, we had excavated the shelter — known as Juukan 2 — in 2014, six years before its destruction. We found evidence Aboriginal people first used Juukan 2 around 47,000 years ago, likely throughout the last ice age, through to just a few decades before the cave was destroyed.

The site held thousands of significant objects including an ancient plait of human hair, tools and other artifacts, and animal remains. The results of the excavation led to last-minute efforts to stop the destruction of the site, but they were unsuccessful.

The full results of the excavation are published for the first time today in Quaternary Science Reviews.

Where is Juukan and what happened there?

Juukan is a gorge system with a series of caves in Puutu Kunti Kurrama Country, approximately 60 kilometers [37 miles] north west of Tom Price, in the Pilbara region of Western Australia.

The Juukan 2 rockshelter is one of the caves that make up this system. It was once part of a deep gorge featuring fresh water holes, large camping areas surrounded by massive ironstone mountains and a large river that flowed at some times of the year and was dry at others.

RELATED: Drowned land off Australia was an Aboriginal hotspot in last ice age, 4,000 stone artifacts reveal

Today the area is part of a Rio Tinto iron ore mine. As widely reported in May 2020, the Juukan 2 rockshelter was destroyed during mine expansion activities. While Rio Tinto held ministerial consent to destroy the heritage site, the action was against the wishes of the Traditional Owners.

The destruction led to widespread global condemnation and shone a spotlight on Western Australia's substandard heritage protection legislation.

What is so significant about Juukan?

Juukan Gorge is named after a Puutu Kunti Kurrama ancestor. It is extremely significant both for cultural and scientific reasons.

For the Puutu Kunti Kurrama, Juukan is a deeply spiritual place that contains deep-time evidence of their presence and association with the landscape in their Traditional Country.

In terms of the scientific significance of Juukan 2, the site is one of the oldest known locations of Aboriginal settlement of Australia. While there are some sites that have been found to be older, such as Madjedbebe in Kakadu in the Northern Territory and off the Western Australian coast, there are only a few places as old as Juukan in inland Australia.

Juukan is about 500 kilometers [310 miles] from the coast today. Up until approximately 10,000 years ago, when sea levels rose, it was almost 1,000 kilometres inland.

This means people living around Juukan were adept at living in the desert. This is also shown by the fact they were able to continue to use the cave even during the last ice age (from around 28,000 to 18,000 years ago). Archaeologists have found very little direct evidence from this period at any other sites.

Often just a handful of artifacts is regarded as enough evidence to show people used an archaeological site. However, at Juukan 2 we found thousands of artefacts, including many that featured resin from spinifex grass, which was likely used as a kind of glue to hold together the pieces of composite tools.

Juukan 2 also held amazing evidence of animals over the ages. We found broken bones from animals that had died naturally, and also bones associated with people cooking and eating kangaroos, emus, and even echidnas at the site.

Among this material was a plait of human hair dated to around 3,000 years old. The hair was DNA tested and the results told us it was likely related to the Traditional Owners who were part of the excavation team.

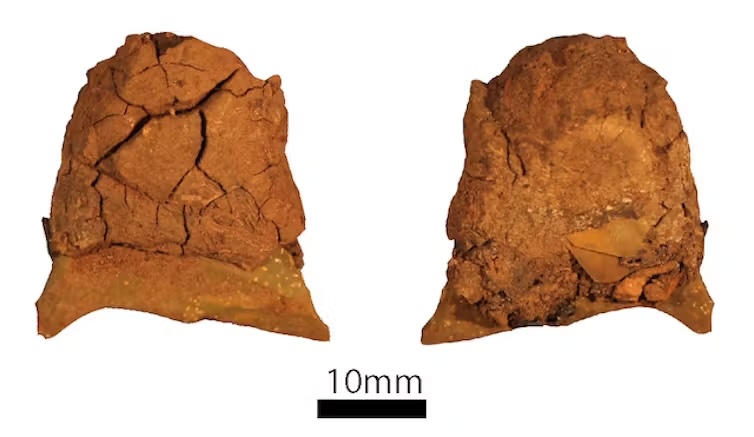

The material we found was extremely well preserved. We even found a bone point made from a kangaroo's shinbone around 30,000 years old with ochre on its end. We don't know what this was used for, but the ochre may indicate a ritual function.

What now?

After the blast in 2020, we began to re-excavate the site. Over the past two years we have removed about 150 cubic meters [5,300 cubic feet] of rubble that was once the roof and back wall of the cave. Beneath the debris we found traces of organic material, and then remnants of the cave floor.

Excavations have now reached the original floor level throughout most of the site, and we are carefully digging and finding more incredible materials. This includes more plaited hair, shell beads we think were brought from the coast, and fragments from the jaw of a Tasmanian devil, an animal which has been extinct on mainland Australia for over 3,000 years.

The publication of these results from 2014 is just the next chapter in the archaeology of Juukan 2, a place special to the Traditional Owners, but also of immense significance to science and our understanding of cultural heritage of Australia.

The Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura Aboriginal Corporation is a co-author of this article and the associated research, recognised collectively according to their cultural preference.

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Michael is one of Australia's leading archaeological consultants, specialising in remote arid and semi arid environments. He is Director of Scarp Archaeology, one of the premier archaeological consulting companies in Australia specialising in large, complex projects for major industry. Scarp has offices and staff throughout Australia and a network of specialist experts. Michael has qualifications in archaeology and in history from Sydney University, the Australian National University, and University of New South Wales.