7,000-year-old alien-like figurine from Kuwait a 'total surprise' to archaeologists

A newfound clay head from the sixth millennium B.C. is the first of its kind ever found in Kuwait, but similar finds have been unearthed from ancient Mesopotamia.

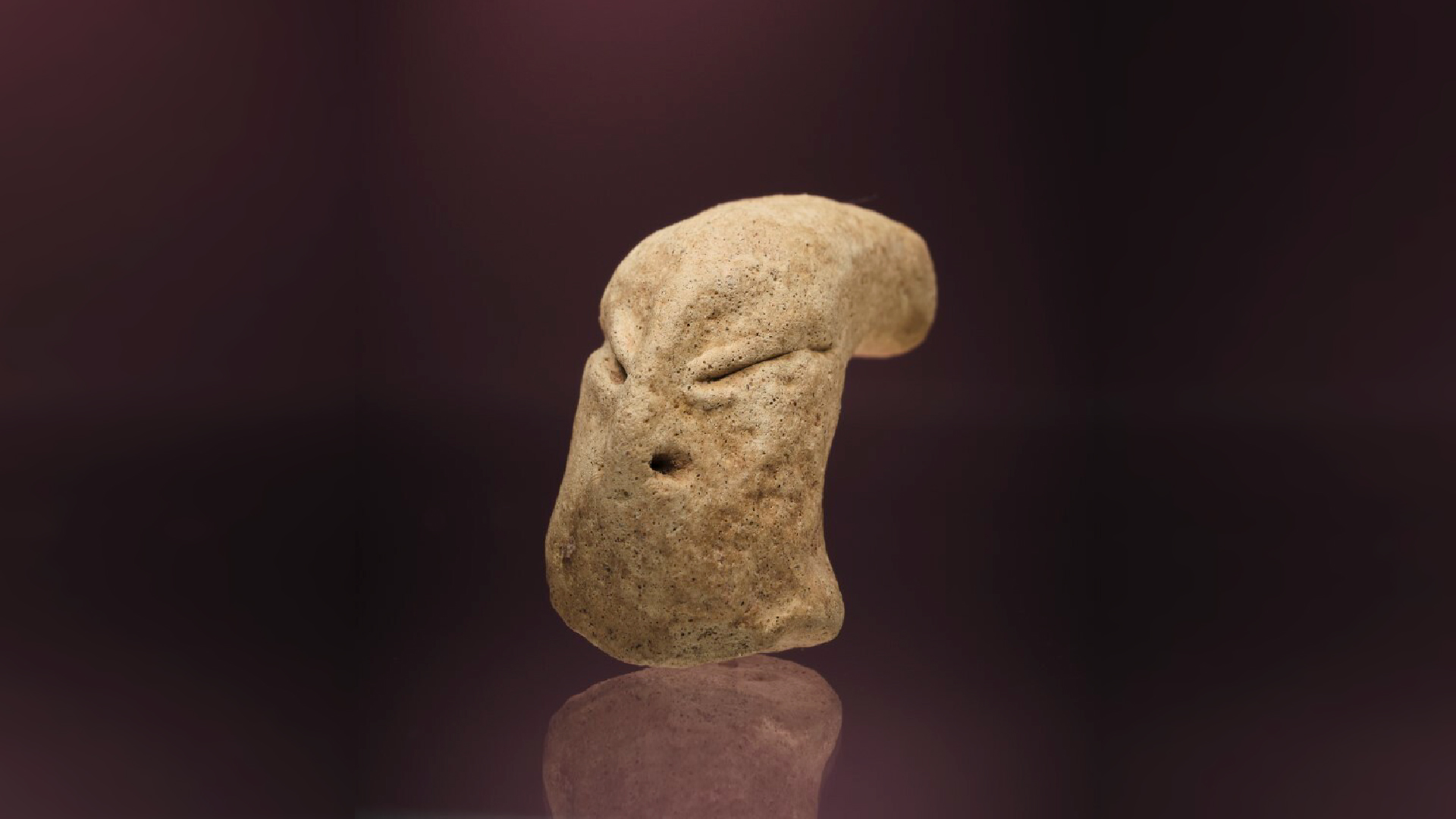

Archaeologists in Kuwait have discovered a 7,000-year-old clay figurine that looks eerily similar to a modern-day depiction of an alien.

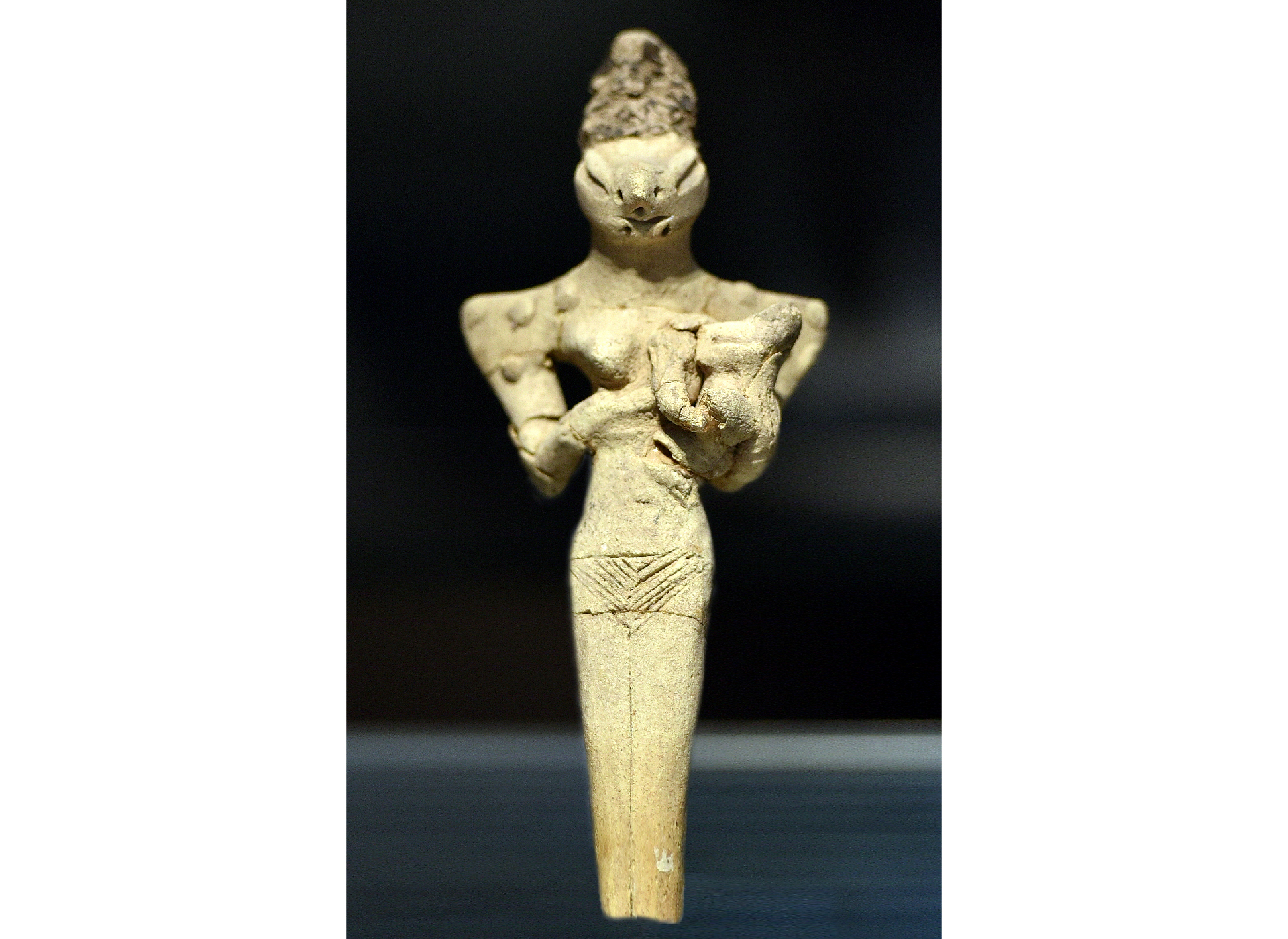

But while this figurine may look more supernatural than human, its style was common in ancient Mesopotamia, although it's the first of its kind ever to be found in Kuwait or the Arabian Gulf.

The small, finely crafted head, with slanted eyes, a flat nose and an elongated skull, was found during excavations this year at Bahra 1, a prehistoric site in northern Kuwait where a joint Kuwaiti-Polish team has been excavating since 2009. Bahra 1 was one of the Arabian Peninsula's oldest settlements, with occupation lasting from around 5500 to 4900 B.C.

During this time, Bahra 1 was settled by the Ubaid, a culture that originated in Mesopotamia and is known for its distinctive pottery, including its alien-like figurines. The Ubaid intertwined with Neolithic, or New Stone Age societies in the Arabian Gulf in the sixth millennium B.C. and turned the area into a sort of ancient melting pot, said Agnieszka Szymczak, an expedition leader at Bahra 1 in charge of the small finds at the site, like the newly discovered figurine.

The collision of these peoples and their cultures resulted in a "prehistoric crossroads of cultural exchange," Szymczak, an archaeologist at the University of Warsaw's Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, told Live Science in an email. Part of this exchange included art, like the recently unearthed figurine.

Related: Lumpy flint figurines may be some of the earliest depictions of real people

"[The] discovery of the figurine was a total surprise for the whole team, as it was the first such find not just among the over 1.5k [1,500] small finds excavated from the Bahra 1 site but also from the Arabian Gulf region," Szymczak said. Moreover, it's made of Mesopotamian clay, not like the "Coarse Red Ware" ceramics local to the Arabian Gulf, meaning the Ubaids were actively importing their homegrown traditions into the region.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ubaid figurines are sometimes called "lizard-headed," "bird-like," or "ophidian" meaning "snake-like," according to University of Chicago publications. The newfound figurine is likely "imbued with symbolic meaning," Szymczak said, even though the figurine was discovered in a "mundane activity area," not in a special or symbolic place — like the graves they've been found in throughout Mesopotamia.

Aurelie Daems, a Near Eastern archaeologist at Ghent University in Belgium who has written book chapters on Ubaid ophidian figurines but was not involved in the current study, praised the find at Bahra 1 as having the "potential to clarify research questions related to ritual and social practices" of the Ubaid, as well as the relationships between the prehistoric Gulf region and Mesopotamia.

Various theories have attempted to explain the unusual facial features of these figurines. One idea suggests the sculptures show artificial cranial deformation, otherwise known as "head-shaping," a practice followed in Ubaid society, and evidenced in skeletal remains excavated in Mesopotamia. Achieved by wrapping bandages around an infant's malleable skull, head-shaping could have been utilized by the Ubaids as a symbol of identity, such as class, culture or belonging to a special group within their settlement. The Ubaid may have picked up this practice in what is now Iran in the eighth and seventh millennia B.C., and head-shaping hit its peak in Ubaid society during the fifth millennium B.C.

Excavations at the site are ongoing, as are studies on the clay figurine head found this year.

Hannah Kate Simon is an archaeologist and art historian with a focus on Roman art and archaeology. Hannah holds a Master's degree in the history of art and archaeology from New York University's Institute of Fine Arts, as well as two bachelor degrees in Art History and Theatre from Indiana University of Pennsylvania. She previously worked at NYU's Grey Art Gallery as a contributor to its exhibition catalogues, interned at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, and excavated at Aphrodisias, an ancient Greek City in what is now Turkey.