'A king will die': 4,000-year-old lunar eclipse omen tablets finally deciphered

Tablets added to the British Museum's collection many decades ago have finally been deciphered.

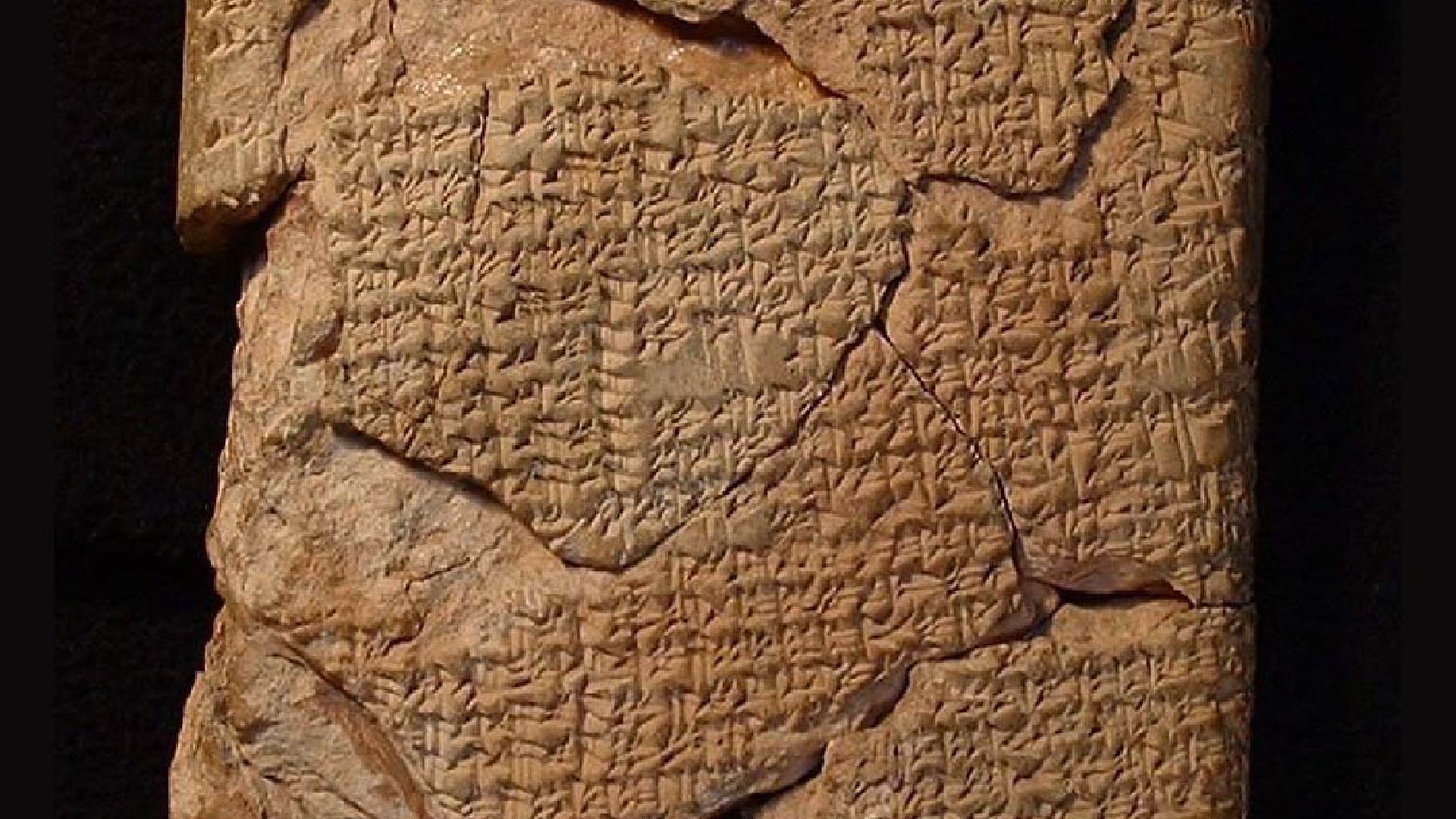

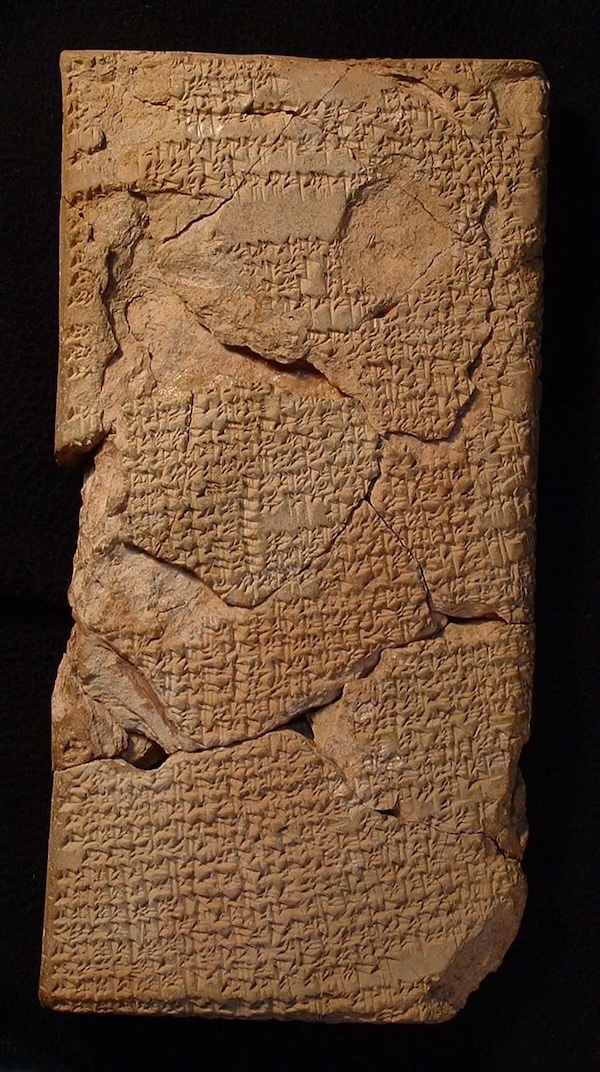

Scholars have finally deciphered 4,000-year-old cuneiform tablets found more than 100 years ago in what is now Iraq. The tablets describe how some lunar eclipses are omens of death, destruction and pestilence.

The four clay tablets "represent the oldest examples of compendia of lunar-eclipse omens yet discovered" Andrew George, an emeritus professor of Babylonian at the University of London, and Junko Taniguchi, an independent researcher, wrote in a paper published recently in the Journal of Cuneiform Studies. (Lunar eclipses occur when the moon falls into Earth's shadow.)

The authors of the tablets used the time of night, movement of shadows and the date and duration of eclipses to predict omens.

For example, one omen says that if "an eclipse becomes obscured from its center all at once [and] clear all at once: a king will die, destruction of Elam." Elam was an area in Mesopotamia centered in what is now Iran. Another omen says that if "an eclipse begins in the south and then clears: downfall of Subartu and Akkad,"which were both regions of Mesopotamia at the time. Yet another omen reads: "An eclipse in the evening watch: it signifies pestilence."

It's possible that ancient astrologers used past experiences to help determine what omens the eclipses portended.

"The origins of some of the omens may have lain in actual experience — observation of portent followed by catastrophe," George told Live Science in an email. However most omens were likely determined through a theoretical system that linked eclipse characteristics to various omens, he noted.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The cuneiform tablets probably come from Sippar, a city that flourished in what is now Iraq, George told Live Science. At the time the tablets were written, the Babylonian Empire flourished in parts of the region. The tablets became part of the British Museum's collection between 1892 and 1914 but had not been fully translated and published until now.

Trying to predict the future

In Babylonia and other parts of Mesopotamia, there was a strong belief that celestial events could predict the future.

People believed that "events in the sky were coded signs placed there by the gods as warnings about the future prospects of those on earth," George and Taniguchi wrote in the article. "Those who advised the king kept watch on the night sky and would match their observations with the academic corpus of celestial-omen texts."

Kings in ancient Mesopotamia didn't rely on those eclipse omens alone to predict what was coming.

"If the prediction associated with a given omen was threatening, for example, 'a king will die,' then an oracular enquiry by extispicy [inspecting the entrails of animals] was conducted to determine whether the king was in real danger," George and Taniguchi wrote.

If the animal entrails suggested that there was danger, people believed they could perform certain rituals that could annul the bad omen, thereby countering the forces of evil that lay behind it, George and Taniguchi wrote.So even if the omens were bad, people still believed that the forecasted future could be avoided.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.