AI identifies 3 more 'Nazca Lines' figures in Peru

The deep-learning system is 21 times faster than a human at finding ancient "geoglyphs" in aerial photographs of Peru's Nazca Desert.

Scientists have used artificial intelligence to discover three lost "Nazca Lines" figures in Peru that were etched into the desert up to 2,400 years ago.

The largest newfound figure — a pair of legs — is more than 250 feet (77 meters) across. The researchers also discovered the figure of a fish measuring 62 feet (19 m) across and 56 foot-wide (17 m) bird.

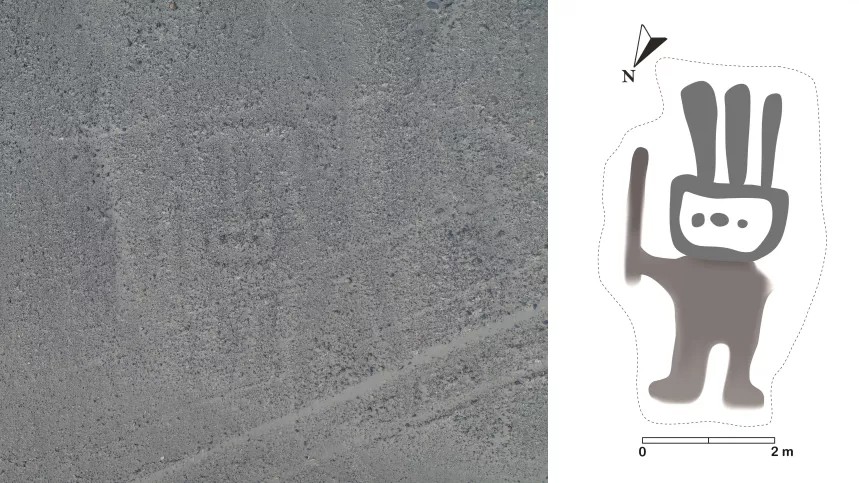

Scientists previously used the same method to identify a humanoid figure measuring about 13 feet (4 m) long and 6.5 feet (2 m) across, they announced in 2019.

These figures, or geoglyphs, are incised into the surface of the Nazca Desert, usually by moving black stones to reveal white sand underneath.

More than 350 geoglyphs have now been rediscovered. Pilots spotted the first lines and geometric patterns in the Peruvian desert, or pampas, in the 1920s, and later research uncovered vast geoglyphs depicting hummingbirds, monkeys, whales, spiders, flowers, geometric designs and tools.

Related: Stunning images of the mysterious Nazca Lines in Peru

While most of these figures are in the Nazca (or Nasca) Desert, they are also found elsewhere in Peru. Archaeologists think they were made between 400 B.C. and A.D. 650.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers reported the new geoglyphs in the July edition of the Journal of Archaeological Science.

The exact purpose of the Nazca Lines is a long-standing mystery, but most archaeologists now think they were probably used for ceremonial processions along the outlines of the figures, the researchers wrote in the study.

Desert lines

Study lead author Masato Sakai, a professor of anthropology and archaeology at Yamagata University in Japan, has been searching for Nazca geoglyphs since 2004 using satellite imagery, aerial photography, airborne scanning lidar and drone photography.

It took Sakai's team at Yamagata's Institute of Nasca roughly five years to analyze high-resolution aerial photographs of the entire region, during which time they identified several new geoglyphs.

But when they obtained even higher-resolution aerial photographs in 2016, they turned to an artificial intelligence method known as "deep learning" to examine them — in partnership with IBM Japan and IBM's Thomas J. Watson Research Center in the United States, which conducts advanced studies of artificial intelligence.

Deep-learning systems and the methods they use to handle data are inspired by the way the human brain processes information. Usually, a deep learning system is trained on thousands or millions of known objects, but Sakai and his colleagues trained this one with data from just 21 known Nazca geoglyphs, which they divided into "elements."

Any known geoglyph is made of a dozen of these elements — such as a head, a torso, an arm, or a leg. And so the new deep-learning system was able to find just parts of geoglyphs, Sakai told Live Science in an email.

Related: Aerial investigation reveals 168 previously unnoticed Nazca Lines in Peru

On-site surveys

The AI identified possible figures about 21 times faster than a trained archaeologist; and scientists traveled to the sites of the most likely candidates to verify that they actually existed. The results are the four geoglyphs described in the study.

The authors wrote that the system could be useful in cases where human experts might overlook geoglyphs in aerial photographs: The newly discovered humanoid geoglyph, for example, was near Nazca's famous hummingbird geoglyph but had never been spotted before.

Finding these ancient Nazca Lines now is important as many geoglyphs face destruction, especially from erosion and climate change, which can produce more rain and damage the surface lines. "It is imperative to identify and protect as many geoglyphs as possible," the authors wrote.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.