Ancient DNA from South Africa rock shelter reveals the same human population stayed there for 9,000 years

Ancient human genomes reconstructed from remains at a southern African rock shelter show remarkable genetic continuity over time.

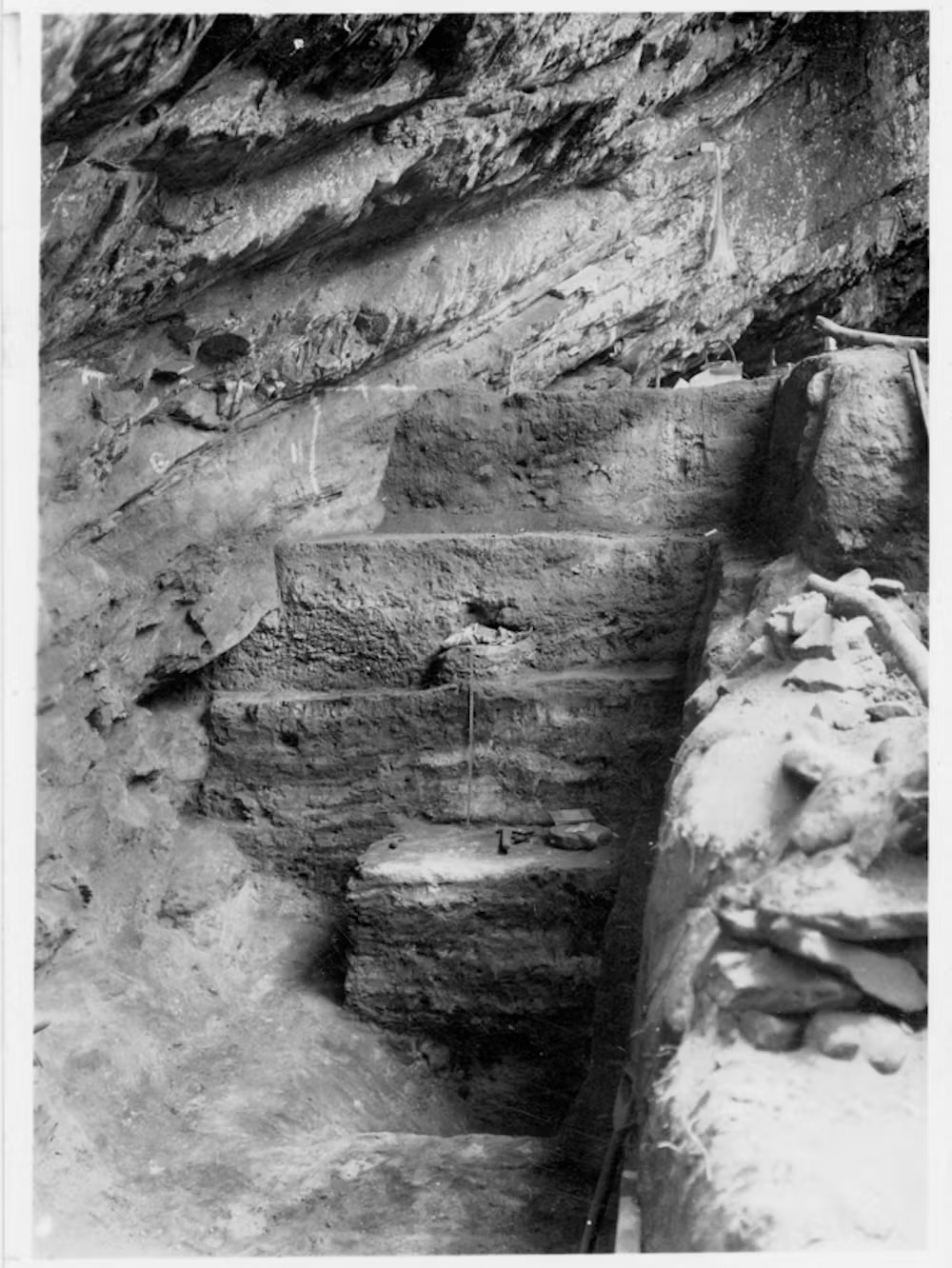

Oakhurst rock shelter is an archaeological site near the town of George on the southern coast of South Africa. It is set into a sandstone cliff above a stream in a valley forested by towering old yellowwood trees.

Archaeologists first started excavating Oakhurst in the 1930s. What makes the site special is the record of human occupation there, which spans 12,000 years. Not only have rock art, stone tools and ceramic fragments been found there, but also the remains of 46 people. That's rare: most very old burials found in South Africa (from the last 40,000 years) have been of single individuals.

New technology is making it possible to keep learning more from previously discovered archaeological material. For our own research team, Oakhurst offered an opportunity to reconstruct the genomes of the site's inhabitants through time, and to assess their genetic relationships to people living in the region today.

A genome is the genetic information about a living organism. This information gets passed down from one generation to the next, forming a record of the past. Studying ancient genomes — a field known as archaeogenetics — helps us understand the history of living people and the movements of populations.

We were able to generate 13 ancient genomes from skeletal human remains at Oakhurst. They included the oldest ancient DNA from the region to date, from two individuals who lived around 10,000 years ago.

The findings show that the population history of southernmost Africa is different from other regions of the world. People didn't arrive here in waves, replacing other populations and mixing with them. Instead there was long-lasting genetic continuity throughout the entire span for these 13 individuals, from 10,000 until as recently as 1,300 years ago.

Human genetic diversity and history

Archaeogenetics has revealed much about human history in Asia and Europe. There has been less success in Africa, because of the environmental conditions. Ancient DNA isn't well preserved when average temperatures are high. So far, fewer than two dozen genomes from South Africa, Botswana and Zambia have been published.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But Africa is interesting as it is the continent with the greatest human genetic diversity. All of the remaining world's human genetic diversity is just a subset of Africa's. So human history cannot be understood without understanding African history.

Related: DNA reveals inbreeding, smallpox and violent ends among cave-dwelling Christians in medieval Spain

Our Oakhurst study started in 2017, with a team of biological anthropologists, archaeologists, and archaeogeneticists. After getting the necessary permissions, permits and contracts, we sampled 13 individuals from the site. Two samples were 9,000-10,000 years old, four were 5,000-6,000, five 4,000-5,000 and two 1,000-1,500 years old. Their ages were established by radiocarbon dating of bone or tooth collagen. All individuals were adults, five were women and eight were men.

The genetics work required several attempts due to technical challenges caused by poor DNA preservation. We extracted DNA from powdered skeletal material and performed a series of laboratory steps to extract DNA molecules and multiply them often enough so that they could be sequenced.

All of the genomes turned out to be relatively similar to those of contemporary San and Khoekhoe people, who live in the region today, including the ǂKhomani San. We could show that between 10,000 and 1,300 years ago, no ancestry from outside present-day South Africa arrived at Oakhurst rock shelter.

This genetic continuity over a long time is remarkable. In comparison, in Europe and Asia, we see more of a change in the ancient DNA record as major population movements occurred.

But it is not as if there was no change in southern Africa. We do see that these people had cultural innovations over time. Several stone technological shifts are preserved at the Oakhurst site, and around the same time, are similarly found across archaeological sites in South Africa.

Around 2,000 years ago, newcomers arrived in the region, introducing herding, farming and new languages. They began interacting with local hunter-gatherer groups. Still, even the individual we studied who lived 1,300 years ago was genetically similar to the older genomes.

We hope that these new results may open doors for further studies into one of the most culturally, linguistically and genetically diverse regions of the world.

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.