'Pregnant' ancient Egyptian mummy with 'cancer' actually wasn't pregnant and didn't have cancer, new study finds

The mummy of a first-century-B.C. individual found in Egypt was not pregnant and did not have cancer, according to a new CT study.

An ancient Egyptian woman thought to have been pregnant and dying of cancer was actually just embalmed with a technique that mimicked these diagnoses, researchers have concluded, settling a four-year scientific debate.

Nicknamed the "Mysterious Lady," the first-century-B.C. mummy was found in the Egyptian city of Luxor (ancient Thebes) but was brought to the University of Warsaw in Poland in 1826. The mummy was not scientifically studied for over a century.

In 2021, experts with the Warsaw Mummy Project concluded that, contrary to their assumption that the mummy was a male priest based on the sarcophagus, it was actually the remains of a woman in her 20s who was 6.5 to 7.5 months pregnant.

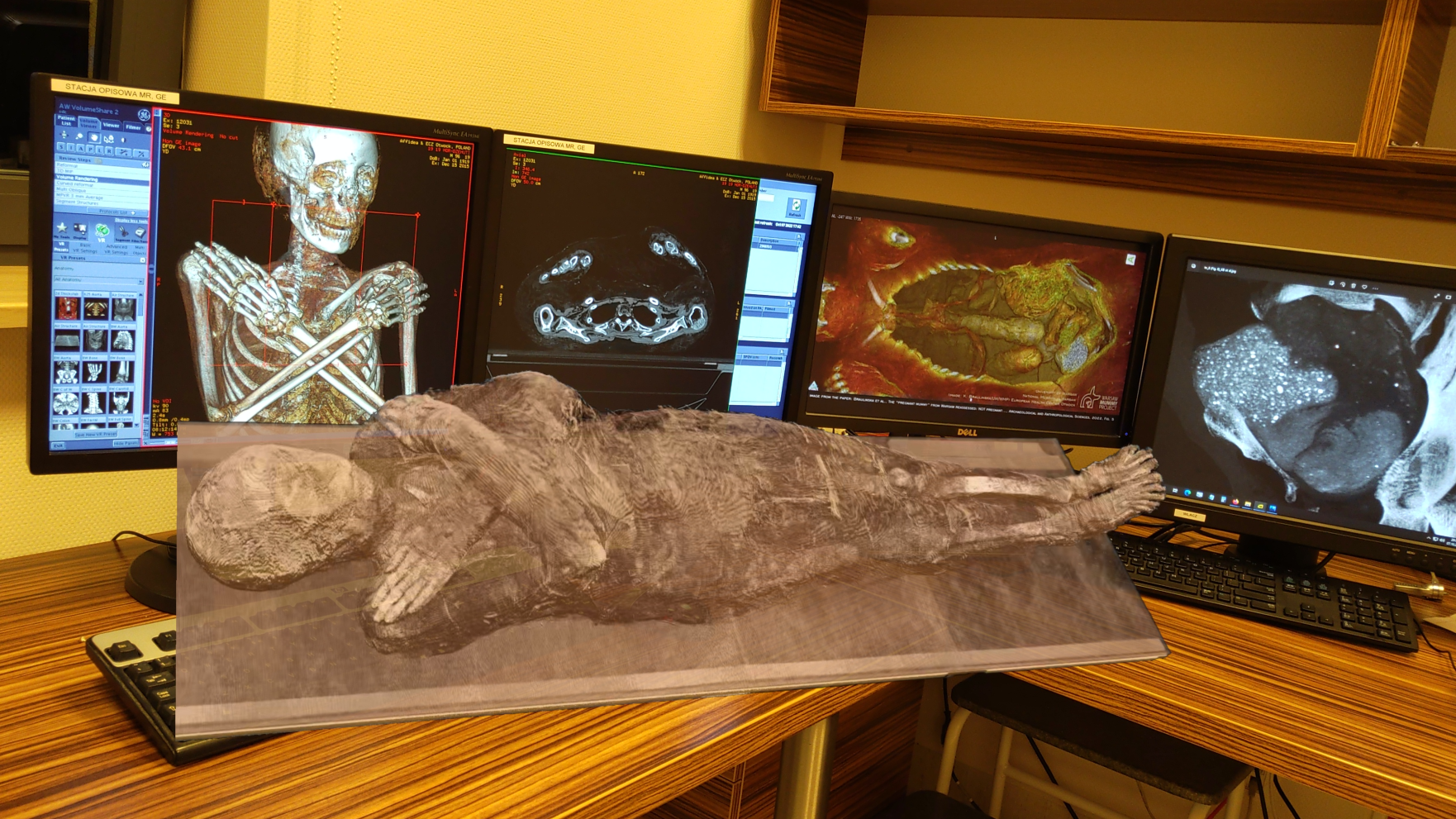

In the first published study of the mummy, researchers used X-ray imaging and CT scans to identify several bundles of mummified organs in her abdomen. They also suggested that a poorly preserved fetus, around 28 weeks in gestational age, could be seen on the scans.

In a second study, the research team proposed that the reason no fetal bones could be clearly identified was that the mother's uterus lacked oxygen and had become acidic over time, essentially "pickling" the fetus. And finally, the team suggested that they had found evidence of potentially fatal nasopharyngeal cancer in the mummy's skull.

These interpretations were controversial, however. Radiologist and mummy expert Sahar Saleem told Live Science in 2022 that the Warsaw team failed to "identify any evidence of anatomical structures to justify their claim of a fetus." Instead, Saleem was convinced the mysterious structures in the mummy's abdomen were embalming packs.

To settle the debate, a team of 14 researchers with varied expertise led by archaeologist Kamila Braulińska of the University of Warsaw studied the Mysterious Lady and published their findings in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences last month.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: Ancient Egyptian teenager died while giving birth to twins, mummy reveals

Members of the research team each examined more than 1,300 raw CT image slices of the mummy produced in 2015 to determine whether there was any radiological evidence of a pregnancy or of cancer.

Every expert who reanalyzed the CT scans concluded that there was no fetus and that the material assumed to be a fetus was actually part of the embalming process. Further, the suggestion that the fetus' skeleton and soft tissue did not show up on the scans because the body was "pickled" is impossible, the researchers noted in the study, because acids within the human body are insufficient to dissolve bone, especially after a body is embalmed.

Similarly, none of the experts on the new study could identify clear evidence of cancer in the mummy. Some suggested instead that the damage to the woman's skull most likely occurred when her brain was removed during the embalming process.

Given the diagnostic consensus of the international panel of experts, the researchers concluded in the study that "this should resolve once and for all the discussion of the first alleged case of pregnancy identified inside an ancient Egyptian mummy, as well as the dispute about the presence of nasopharyngeal cancer."

But given the public's intense interest in the "case of the pregnant mummy" over the past four years, the researchers suggested that, going forward, additional focus should be given to questions of maternal and pediatric health in ancient Egypt.

Mummy quiz: Can you unwrap these ancient Egyptian mysteries?

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Killgrove holds postgraduate degrees in anthropology and classical archaeology and was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.