Rock carvings of ancient Egyptian pharaohs found underwater near Aswan

Archaeologists discovered rock carvings featuring several pharaohs during an underwater expedition near Aswan, Egypt.

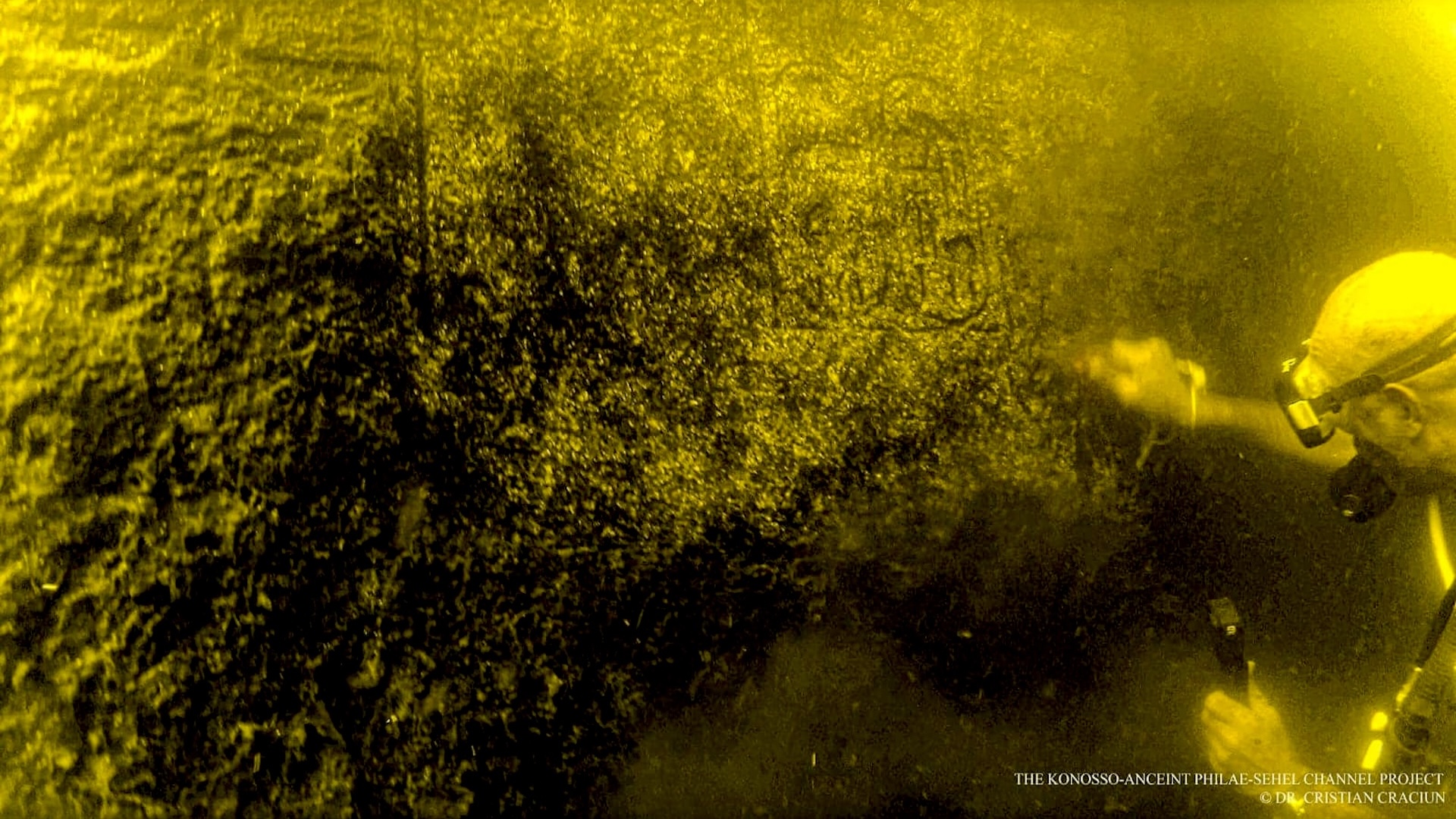

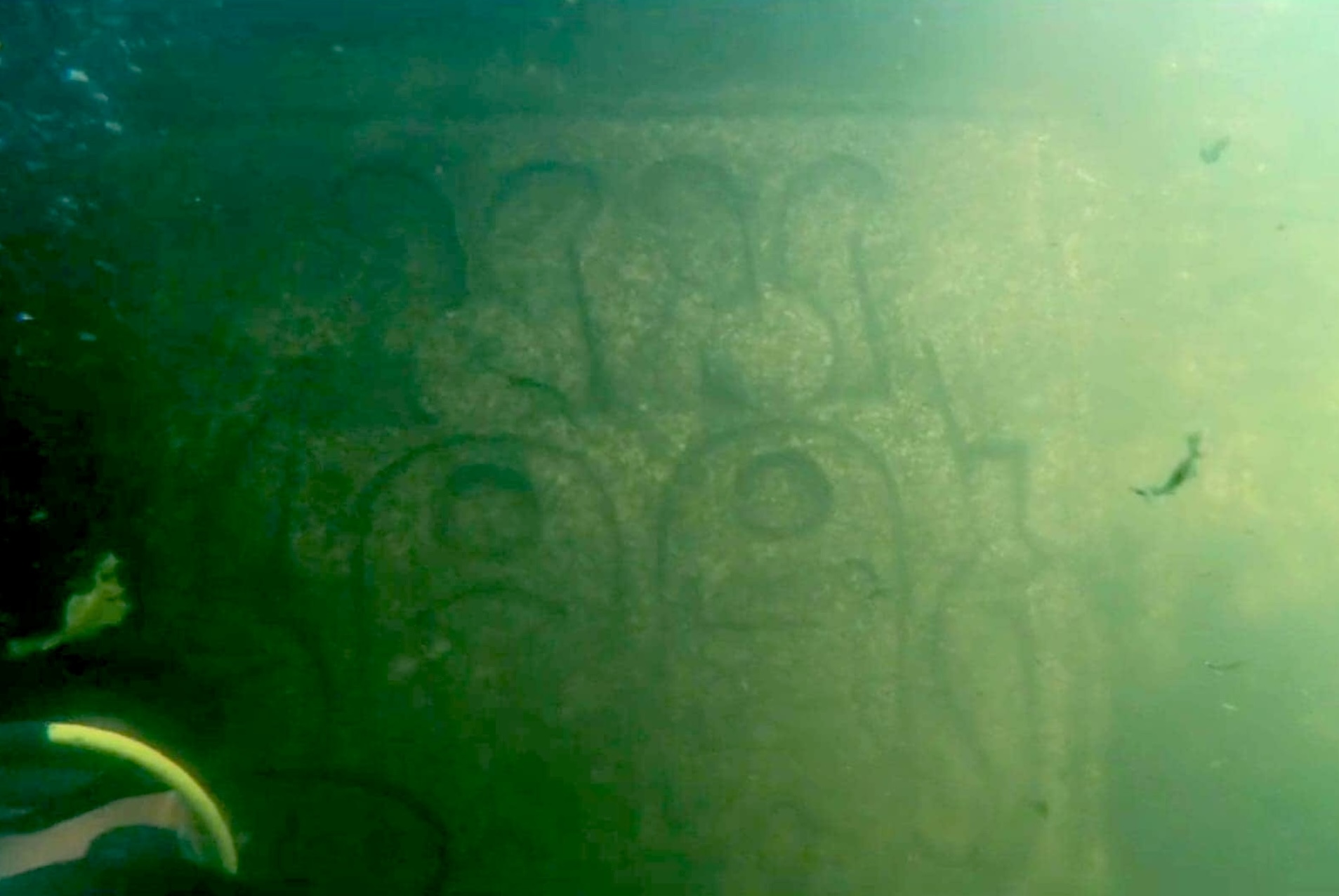

During a diving expedition in the Nile River, archaeologists in Egypt discovered rock carvings featuring depictions of several ancient Egyptian pharaohs, along with hieroglyphic inscriptions.

A joint French-Egyptian team found the carvings underwater south of Aswan in an area that was flooded when the Aswan High Dam was built between 1960 and 1970. Prior to the flooding, there was a large effort led by UNESCO to record and move as many archaeological remains as possible from the area. However, many artifacts could not be relocated in time and were soon submerged by the construction project.

Aswan was important for the ancient Egyptians because at times it was near the country's southern border and a number of important temples are located nearby. These include Abu Simbel, a site that has four colossal statues of Ramesses II (lived 1303 to 1213 B.C.) each about 69 feet (21 meters) tall. Aswan is also home to the Philae temple complex, where the last Egyptian hieroglyphic inscription was written in A.D. 394.

The team's work aims to identify and record surviving inscriptions and carvings that are now underwater, the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities said in a translated statement. To do that, team members are diving down to the remains and recording them using photography, video and photogrammetry, a technique that involves taking dozens of photos of an object that can later be used to create a digital 3D model of it.

Related: 13 treasures the ancient Egyptians buried with their dead, and what they mean

The recently found depictions of pharaohs include those of Amenhotep III (reigned circa 1390 to 1352 B.C.), Thutmose IV (reigned circa 1400 to 1390 B.C.), Psamtik II (reigned circa 595 to 589 B.C.) and Apries (reigned circa 589 to 570 B.C.) — rulers from dynasties 18 and 26, ministry officials wrote in the statement. The statement had little information on what the inscriptions say or what the carvings look like, but it noted that they are well preserved. More remains will likely be found as the team's work continues.

Live Science contacted scientists not involved with the research to get their thoughts on the carvings. Jitse Dijkstra, a classics and religious studies professor at the University of Ottawa, said the finds are interesting but more information is needed to know their significance. William Carruthers, a lecturer in the School of Philosophical, Historical and Interdisciplinary Studies at the University of Essex in the U.K., said the finds show that more remains survived the flooding than UNESCO thought was possible when the organization carried out the salvage campaign in the 1960s and 1970s.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano, an archaeologist who leads excavations at a necropolis near Aswan and a professor of Egyptology and Near Eastern Archaeology at the University of Jaen in Spain, told Live Science that Aswan was an important quarry site for granite and it is possible that the newly found remains were intended for transport to another part of Egypt. Alternatively, they could have been part of temples near Aswan.

Live Science also attempted to reach archaeologists involved with the work, but they did not respond by the time of publication.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.