Scottish boy digging for potatoes found 'masterpiece of Egyptian sculpture' on his school grounds. How did it end up there?

Archaeologists in Scotland may have finally solved the mystery of how ancient Egyptian artifacts that were unearthed in school grounds between 1952 and 1984 became buried there.

Seventy-one years ago, a schoolboy in Scotland was digging up potatoes as a punishment when he discovered an ancient Egyptian statue — the first in a collection of ancient Egyptian sculptures and artifacts buried in the grounds of his school. Now, researchers have finally worked out how the artifacts got to the British Isles.

Between 1952 and 1984, several antique statues were found on the grounds of Melville House — a stately building in Fife county that lodged soldiers during World War II and later served as a boarding school. Teachers and pupils brought each new discovery to museum curators and experts, who identified the statues as ancient Egyptian artifacts, but no one could figure out how they had ended up there.

"This is a fascinating collection, made all the more so by the mystery surrounding its origins in this country," Margaret Maitland, principal curator of the Ancient Mediterranean at National Museums Scotland where most of the objects are housed, said in a statement.

Related: Mystery of 'impossible' ancient Egyptian statue may be solved

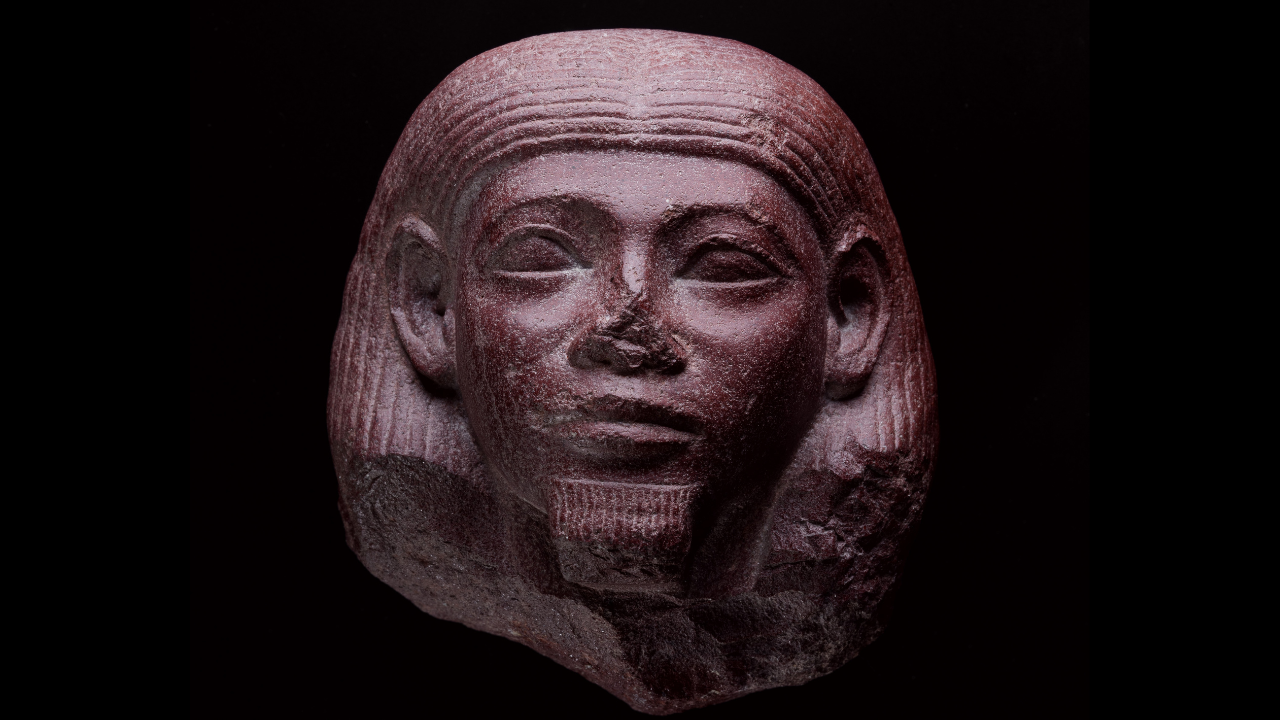

The ancient collection includes a nearly 4,000-year-old statue head carved out of red sandstone, which Maitland described as a "masterpiece of Egyptian sculpture," as well as several bronze and ceramic figurines dating to between 1069 B.C and 30 B.C., or just before the Romans took over Egypt as a province.

In total, 18 ancient Egyptian objects were found buried around Melville House — the only artifacts of their kind formally declared and described in Scotland. Now, for the first time, researchers have unveiled the story of how they arrived on the estate and became buried there.

"Excavating and researching these finds at Melville House has been the most unusual project in my archaeological career, and I'm delighted to now be telling the story in full," Elizabeth Goring, a former curator at the Royal Scottish Museum in Edinburgh (now the National Museum of Scotland), said in the statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 1984, a group of teenage boys from Melville House visited Goring at the museum and brought an Egyptian bronze figurine, which one of them had found with a metal detector on the school grounds. Goring did some digging and learned that two additional Egyptian objects — the sandstone head and a bronze statuette of an Apis bull — had previously turned up on the estate, in 1952 and 1966 respectively.

Goring excavated the site and discovered a number of other ancient artifacts, including the top half of a glazed ceramic figurine depicting the goddess Isis suckling her son Horus, and a ceramic plaque bearing the eye of Horus.

Previous efforts to determine the origin of these objects were fruitless, but researchers now think they were brought there by Alexander Leslie-Melville, whose title was Lord Balgonie — a young heir to Melville House who traveled to Egypt in 1856 and died one year later upon his return to the U.K.

Balgonie may have acquired the collection on his travels, as consuls and antique dealers often sold ancient artifacts to foreigners during this period, according to the statement. After Balgonie's death, family members likely moved the objects to an outbuilding, which was later demolished, and forgot about them.

"The discovery of ancient Egyptian artifacts that had been buried in Scotland for over a hundred years is evidence of the scale of 19th century antiquities collecting and its complex history," Maitland said. "It was an exciting challenge to research and identify such a diverse range of artifacts."

The "fascinating tale" of how Egyptian objects turned up at Melville House contains "mysteries that may never be solved," Goring said. Their story will be published in an upcoming article in the journal Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.