Severed hands buried in ancient Egyptian palace were likely 'trophies' exchanged for gold

Twelve severed hands found buried at an ancient Egyptian palace were likely cut from enemies and exchanged for gold in a ceremony known as "gold of honor," a new study finds.

In a gruesome exchange about 3,600 years ago, the severed right hands of at least 12 individuals were traded for gold and then buried in a royal palace in ancient Egypt, a new study finds.

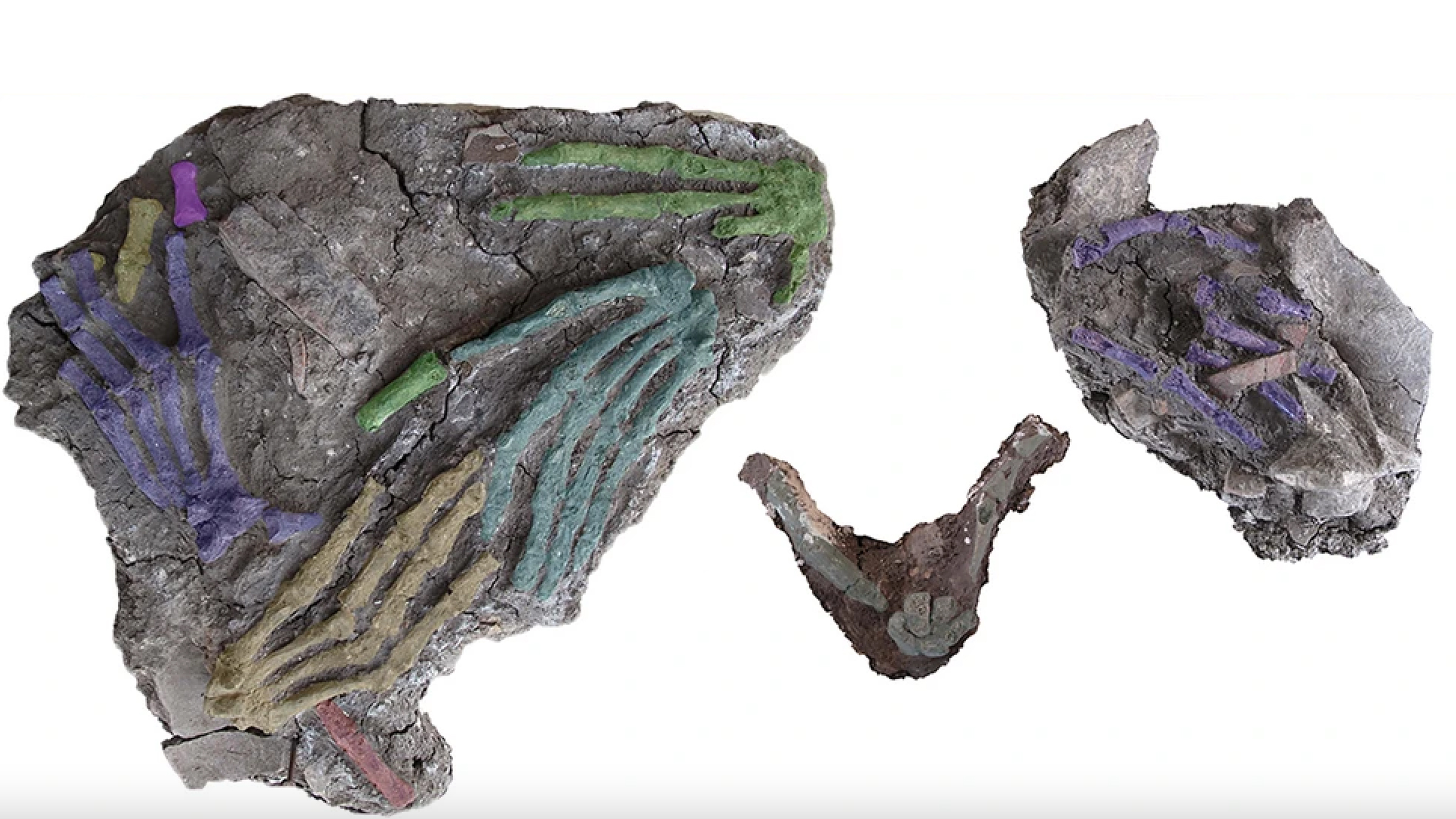

Scientists discovered the severed hands buried in three pits during a 2011 excavation of a courtyard in the palace, located in an ancient city of Avaris (modern-day Tell el-Dab'a) in northern Egypt's eastern Nile delta region. In the new study, researchers suggest that at least 11 of the hands belonged to males, but that the sex of the 12th individual is uncertain, meaning that it could have belonged to a female.

The hand bones showed no signs of age-related degeneration: Rather, these remains likely belonged to adults older than 14 to 21 years old, the team reported in the study, published March 31 in the journal Nature.

At the time the hands were deposited, the Hyksos, a group of people who originated from Asia, controlled part of Egypt and ruled during the 15th dynasty (circa 1640 B.C. to 1530 B.C.) from Avaris.

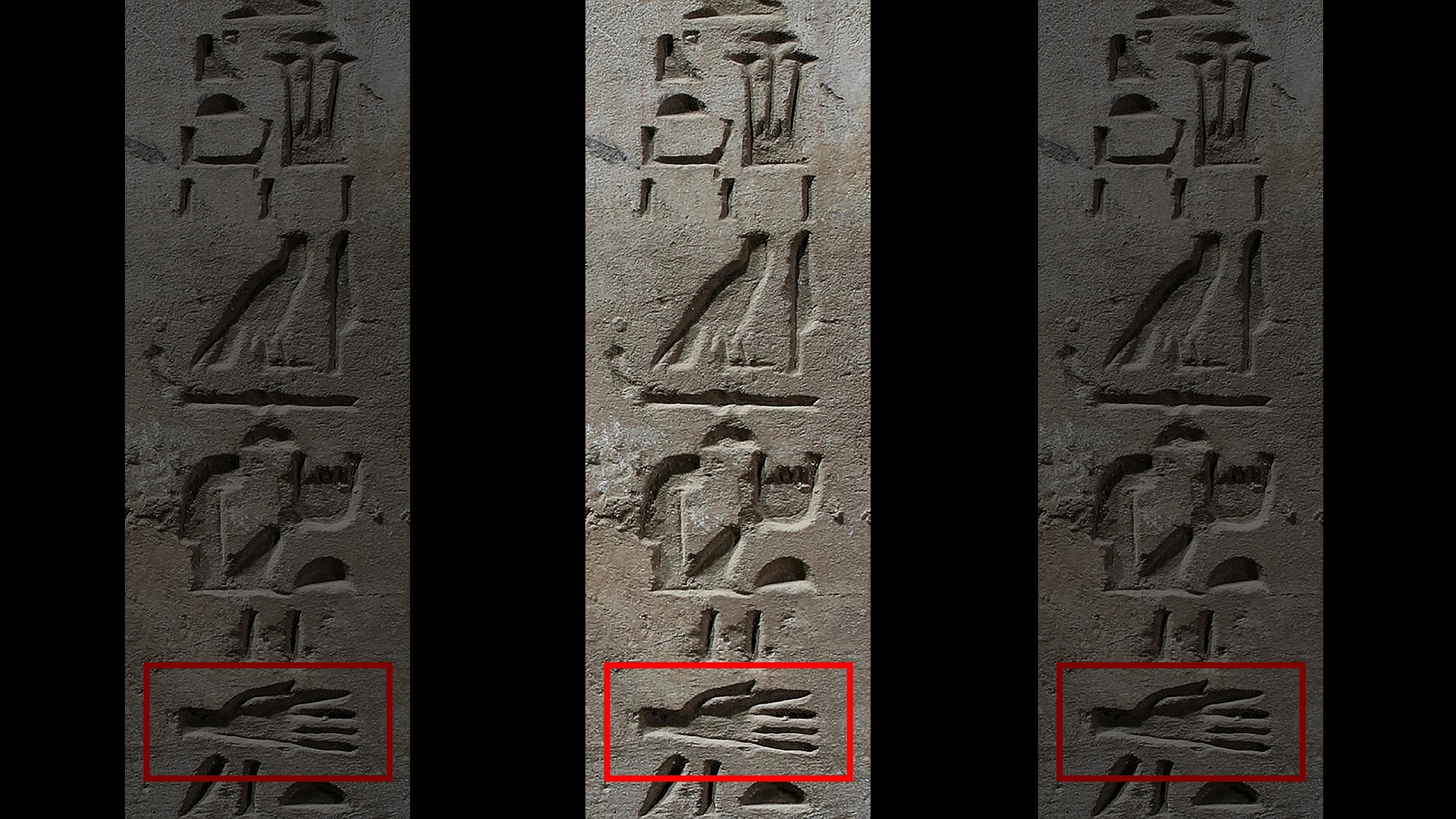

The severed hands are the earliest known physical evidence of a practice known as the "gold of honor," the researchers said. This ceremony, which is described in ancient Egyptian records, involved warriors bringing the severed right hands of enemies in exchange for a rich reward of a collar of gold beads.

Enemies who met this fate were usually men of fighting age, but the presence of a possible female hand is not a surprise, the researchers noted. "Women and warfare did not exist in separate worlds," the team wrote in the study. "On the contrary, they were inextricably linked to the political, social and religious spheres. Consequently, we cannot exclude that the specific hand attested at Tell el-Dab'a belonged to a woman."

These severed remains were likely seen as trophies and handed over during a public event at the palace, the researchers said. They theorized that the Hyksos may have introduced the practice to Egypt and that other Egyptian rulers later adopted it. There are no Egyptian records of this practice occurring prior to the Hyksos period, the researchers noted in the paper.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: Which ancient Egyptian dynasty ruled the longest?

Whose hands were severed?

It's unclear if the hands were severed from living or dead victims, but the acts themselves likely occurred within or near Avaris. It is "rather likely that the hands were taken close to Avaris as they were intact when they were buried and most probably not mummified," study lead author Julia Gresky, a scientist at the German Archaeological Institute in Berlin, told Live Science in an email.

The Hyksos were pushed out of Egypt by forces led by the pharaoh Ahmose around 1550 B.C. But it's unknown if the severed hands came from Egyptian warriors who the Hyksos were fighting, as none of the ancient DNA was preserved in the severed bones, Gresky said.

Anna-Latifa Mourad-Cizek, an honorary research fellow at Macquarie University in Australia who was not involved in the study, praised the discovery. "This is a remarkable find that adds critical information to our understanding of the practices of the inhabitants of Avaris," Mourad-Cizek told Live Science in an email.

Sonia Zakrzewski, a professor of bioarchaeology and bioanthropology at the University of Southampton in the U.K. who was not involved in the research, agreed that the hands were likely offered for the gold of honor.

But she disagreed with the method the team used to determine the sex of the individuals. Because the team was unable to get DNA samples from the hand bones, they calculated the ratio of the second digit to the fourth digit of the hands. The fourth digit is usually longer than the second digit in men, the team noted. Zakrzewski disagrees with the accuracy of this method, noting that women can also have a longer fourth digit.

"I think it's a wonderful find and a great paper, even if I am unconvinced by the certainty of their sexing of the hands," Zakrzewski said.

Editor's note: Updated at 8:23 p.m. EDT to note that Anna-Latifa Mourad-Cizek is an honorary research fellow at Macquarie University.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.