Sphinx may have been built from a natural rock feature eroded by wind, study claims

It's possible that wind erosion made a rock feature in ancient Egypt look something like a sphinx, and then the Egyptians further refined it into the iconic monument.

The ancient Egyptians may have crafted the Sphinx, a 4,500-year-old monument at Giza that stands in front of the pyramid of Khafre not completely from scratch but rather on a natural feature that already looked surprisingly sphinx-like, a new study suggests.

In an Oct. 17 study published in the journal Physical Review Fluids, a team from New York University suggested that a yardang, a windblown ridge of rock sticking out of the ground, can naturally develop into a sphinx-like formation.

However, even if the ancient Egyptians did create the Sphinx from an eerily shaped hunk of rock, they still would have had to delicately fashion the Sphinx's iconic features, which survive to this day, the researchers said.

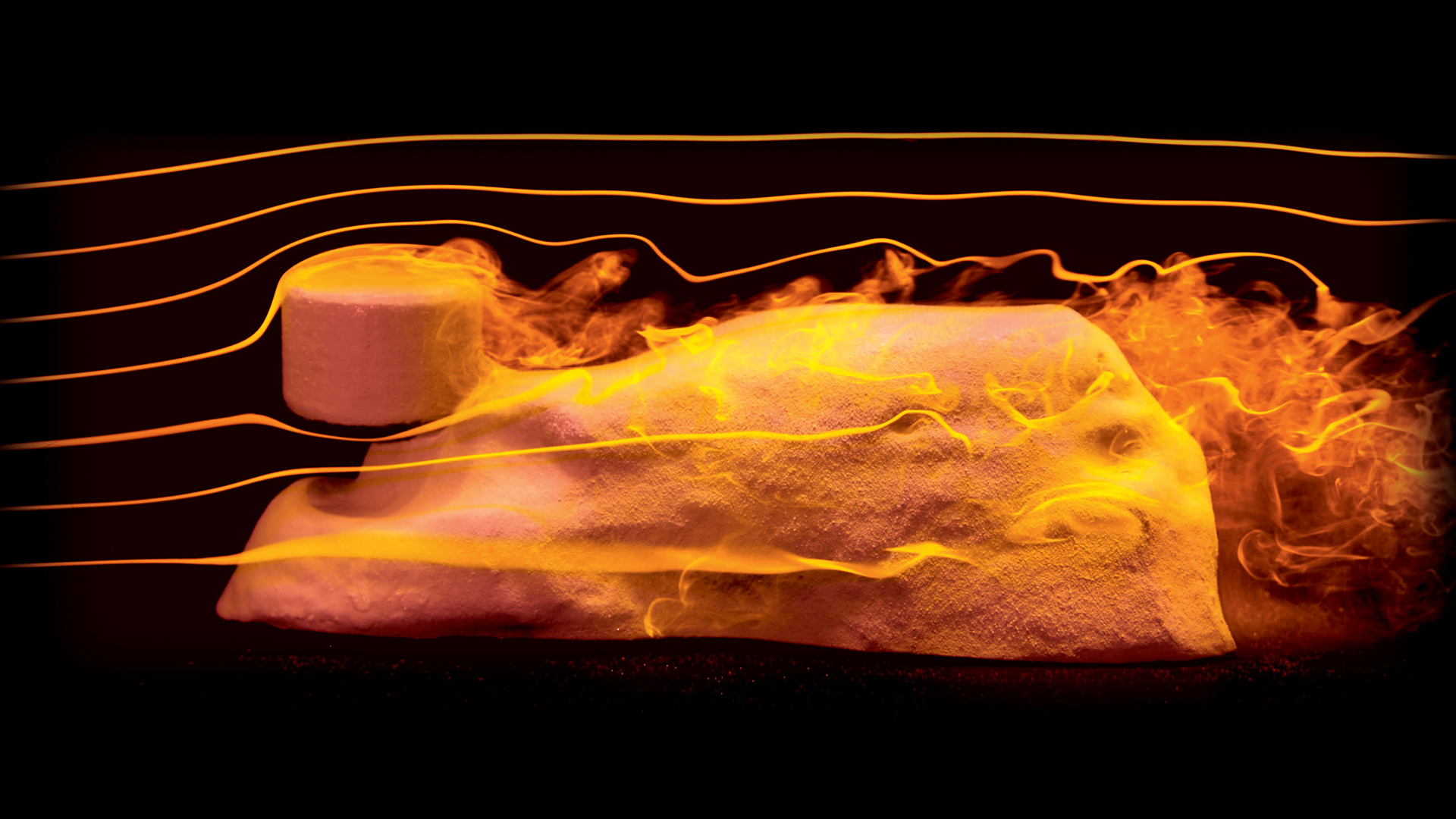

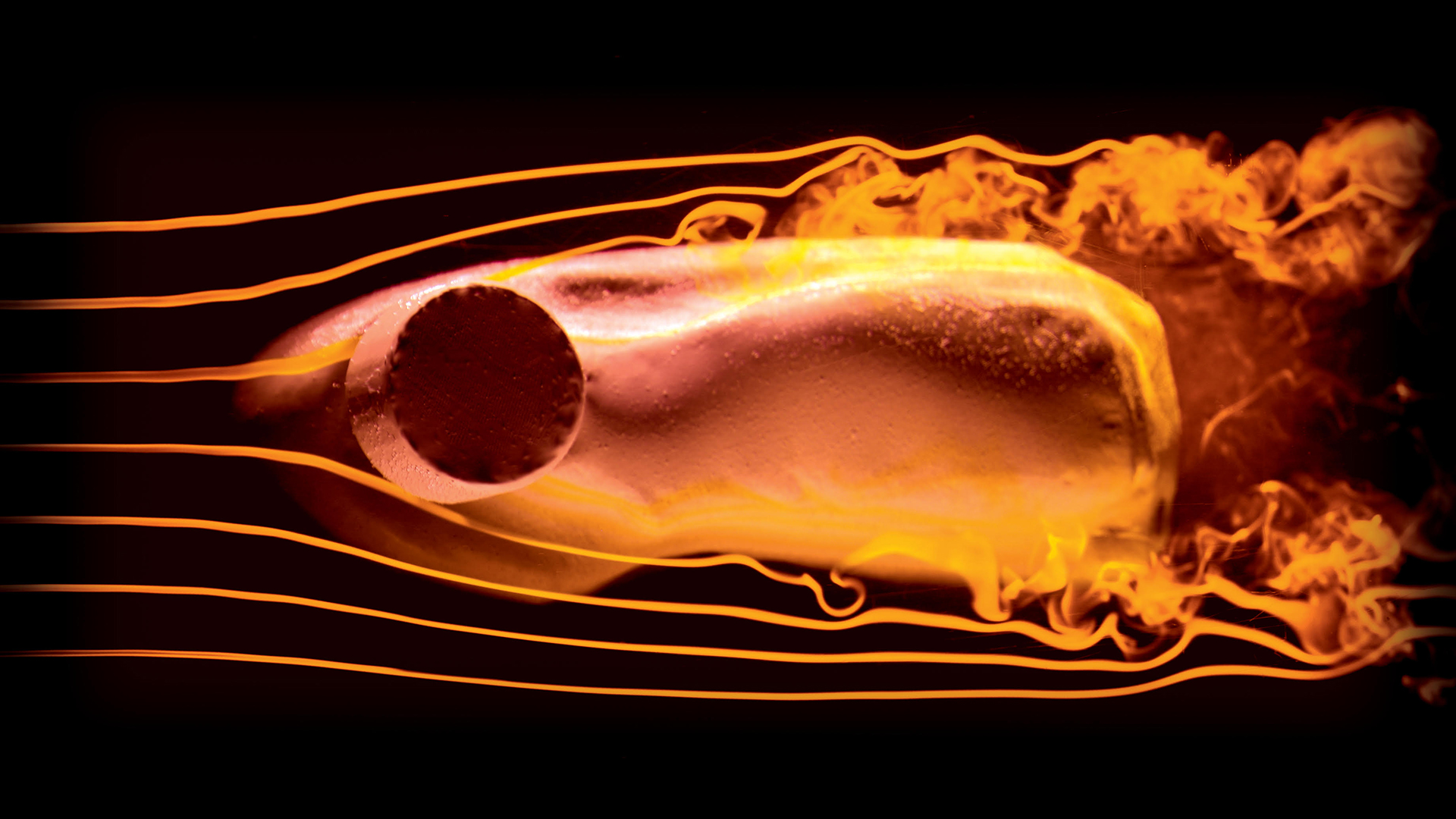

To investigate the Sphinx's shape, the team took a mound of soft clay with harder material inside and placed it within a water tunnel that had a fast-flowing stream meant to simulate thousands of years of wind erosion, the team said in a statement. At the start of the experiment, the team molded the clay into a "half ellipsoid" or half of an oval shape. As the water eroded some of the clay, it left a sphinx-like shape. They found, for instance, that the "harder or more resistant material became the 'head' of the lion," the statement said, with frontal features that looked a bit like a neck and paws also appearing.

We "showed that the natural process of erosion can indeed carve a shape that looks like a lying lion with [a] raised head," study senior author Leif Ristroph, an associate professor of mathematics at NYU, told Live Science in an email. Ristroph cautioned that while it is possible that a natural feature like this existed at Giza, we do not know if it actually did.

Even if a natural feature like this did exist, Ristroph noted, the ancient Egyptians still would have carried out a considerable amount of work to create the iconic structure. There is "no doubt that the facial features and detail work was done by humans," Ristroph said.

Related: Ancient Egyptian pharaoh-sphinx statues unearthed at sun temple

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Egyptologists and other scientists not involved with the study said that while the findings are interesting, it doesn't mean that a natural feature in a sphinx-like shape actually existed at Giza.

The study shows "a very real possibility of how a natural limestone formation came to have a kind of amorphous sphinx-like shape," said Kathryn Bard, a professor emeritus of archaeology and classical studies at Boston University who has conducted extensive work in Egypt. Bard cautioned, however, that although she has seen yardangs at the Dakhla Oasis in Egypt's Western Desert, she has never seen a yardang that looks like the one the team produced in their study.

Even if a sphinx-shaped yardang existed at Giza, the Egyptians would have "had to add onto the natural formation with limestone blocks to complete the front part/lion legs & paws," Bard told Live Science in an email.

Judith Bunbury, a geoarchaeologist at the University of Cambridge who has conducted extensive work in Egypt, told Live Science in an email that "there have been hypotheses in the past that the outline shape of the Sphinx was created by natural erosion." The current study is "a rather nice model to show how a yardang, with a harder patch inside it might come to resemble a [sphinx]," Bunbury said.

Laura Ranieri Roy, an Egyptologist and the founder-director of Ancient Egypt Alive, noted that fieldwork carried out in the 1930s by the archaeologist Émile Baraize suggested that the Sphinx was actually built on two yardangs located close together, with the rear of the Sphinx built atop one yardang and the head and chest of the Sphinx atop another. The work the Egyptians did to build the Sphinx across the two yardangs was extensive, the 1930s research suggested.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.