Ancient princesses helped build vast warrior empire that prompted China to erect the Great Wall

Analysis of ancient DNA and grave goods from burials suggest that princesses helped to build a "massive empire" stretching from Kazakhstan to Mongolia.

Elite women, perhaps princesses, played a crucial role in holding the Xiongnu, one of the first nomadic empires of the eastern Eurasian Steppe, together, a new study suggests.

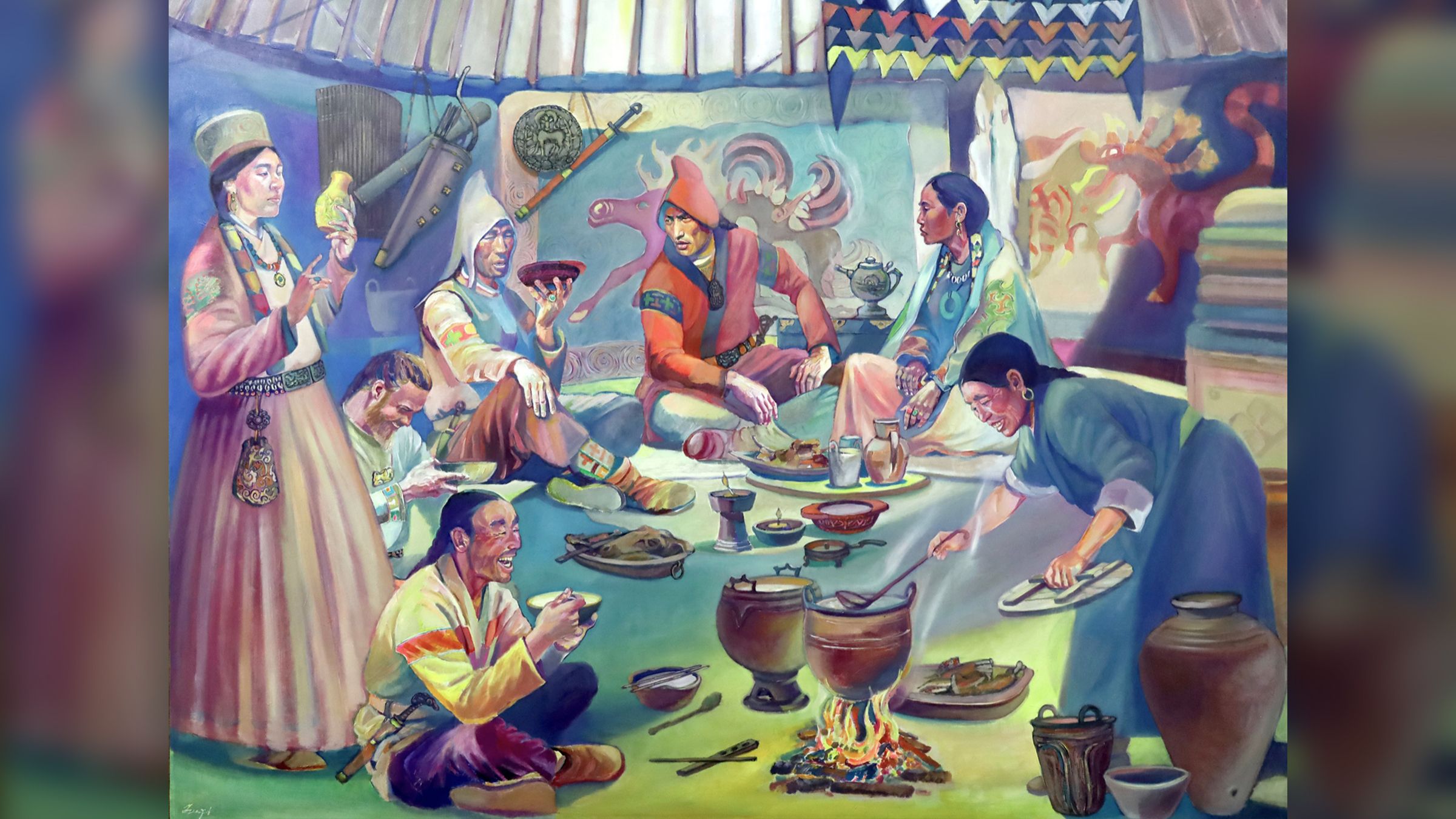

The Xiongnu, who may have been among the ancient ancestors of the Mongols, formed a confederation of nomadic peoples who controlled much of Central Asia, from present-day Kazakhstan to Mongolia, from about the second century B.C. until the first century A.D.

But little is known about them, except for some Chinese records and recent genetic studies based on ancient DNA from their buried remains, said Bryan Miller, an archaeologist at the University of Michigan.

"This was an empire with extreme genetic diversity," he told Live Science. "To call oneself Xiongnu at that time was to call oneself a participant in this massive empire."

Miller is one of the lead authors of a new study exploring the genetics of remains found in Xiongnu graves in the foothills of the southern Altai Mountains, near what would have been the imperial frontier. The research was published in the journal Science Advances on April 14.

Related: Mysterious East Asians vanished during the ice age. This group replaced them.

Nomad princesses

DNA testing at two Xiongnu cemeteries showed that the people buried in the largest tombs were women who were closely related to people from the heartlands of the Xiongnu Empire — roughly in the middle of modern Mongolia — whose genetics were already known.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The women were buried with rich grave goods, including ornamental gold disks, pieces of bronze chariots and horse gear. But the ancient DNA from the remains in the smaller tombs showed a much wider genetic diversity, suggesting those people often came from far-flung regions of the empire — from the Black Sea region to Eastern Mongolia, Miller said.

This finding suggests that the elite families who controlled the Xiongnu Empire probably sent their women to the frontiers in order to cement political alliances with local elites. Miller noted that the most special burials were given only to these elite women, who seem to have been involved in the politics of relatively remote regions.

"They are representatives of the imperial clan that ruled the empire," he said. "You've got these marriage alliances spanning the whole empire, even in these local communities."

Miller said these elite women maintained their high status throughout their lives, which was reflected in their special burials. That suggested they were active participants in the plan, and not just the tools of their male relatives. "They really played an active role," he said. "They were part of it."

Ancient empire

The main source of information about the Xiongnu comes from Chinese records, who saw them as foreign enemies along China's northern and western borders.

Indeed, the name Xiongnu is thought to be a pejorative term, because its Chinese characters also spell "fierce slave."

Miller said that some of the earliest fortifications of what later became the Great Wall of China were built in an attempt to stop Xiongnu raids into Chinese lands. "It was a way to control that very vibrant frontier," he said.

Eventually, the Xiongnu were divided by civil wars. Some groups became tributaries of Chinese states, while some were conquered by other steppe peoples.

Archaeologist Ursula Brosseder of the University of Bonn in Germany, who wasn't involved in the research, said the new study showed how the investigation of ancient DNA was moving away from the large-scale genetics of populations and toward the genetics of particular localities.

"The field of ancient genetics is now shifting," she told Live Science. "So far, most of the studies we have seen concerned the genetics of population structures, such as when large migrations happened. But with this study, we've just zoomed into one society and used genetics as a tool to get a better understanding of how that society worked," she said.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.