Ancient Scythians used human skin for leather, confirming Herodotus' grisly claim

The ancient Scythians, a nomadic people known for their gold and warrior ways, used human skin for leather, a new study finds.

The ancient Scythians — nomadic warriors and pastoralists who flourished on the steppes of Europe and Asia — turned human skin into leather, a new study finds.

The discovery confirms a claim made by the ancient Greek historian Herodotus that the Scythians (circa 800 B.C. to A.D. 300) used human flesh for leather.

To investigate, researchers analyzed 45 samples of leather from 18 burials from 14 sites in southern Ukraine, according to the study, published Dec. 13 in the journal PLOS One. The leather objects were excavated at different times over the past few decades.

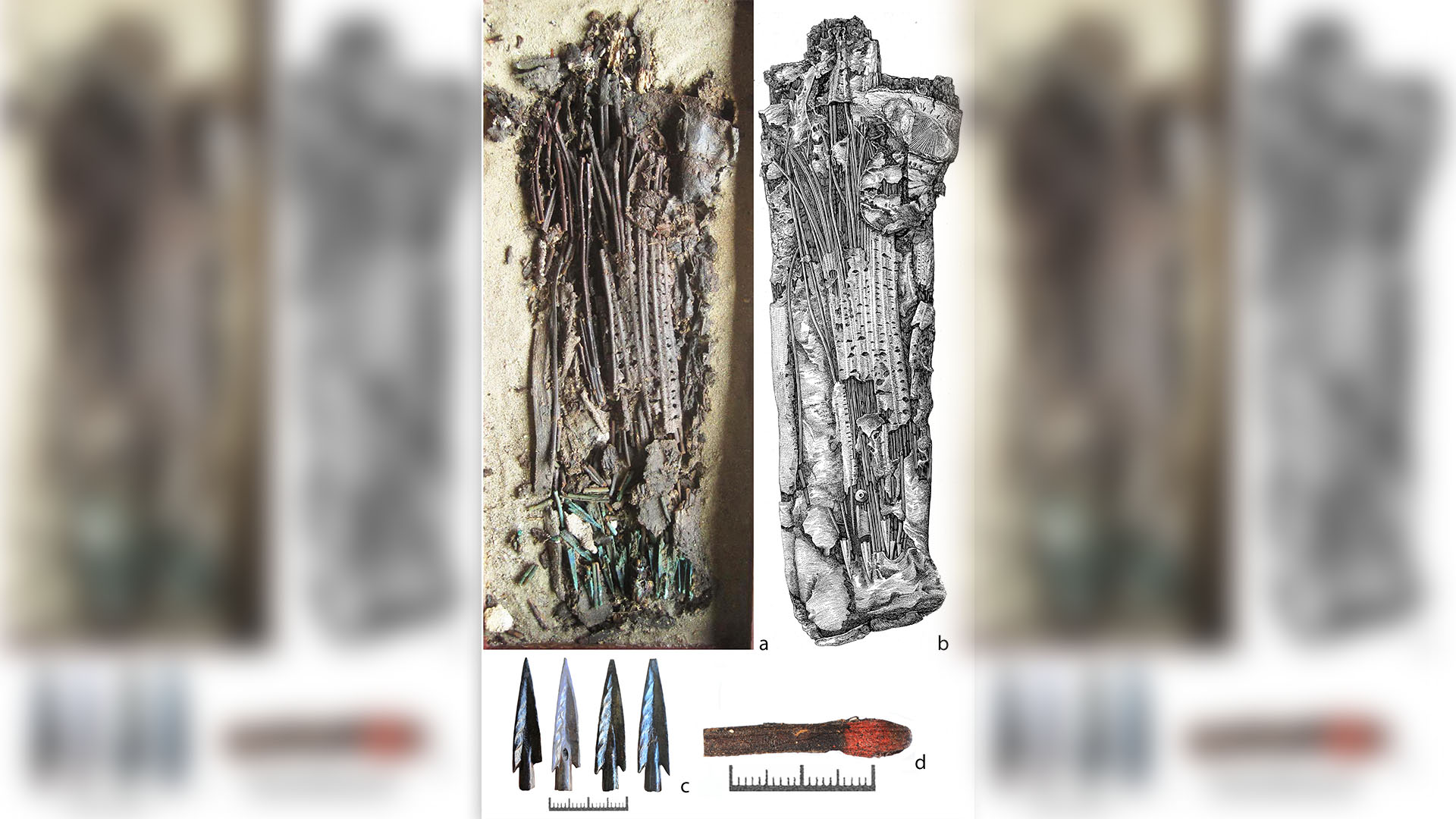

The team found that two leather samples — both of which come from quivers, or containers that held arrows — were made of human skin. Leather from animals — including sheep, goats, cattle and horses — was also used in the construction of the quivers. The quivers were buried in kurgans — mounds that held the burials of rulers or other high-ranking individuals — and date back around 2,400 years to when the Scythians were thriving.

"Considering that quivers were an important element of Scythian warrior identity it is very likely that the quivers ended up being buried with their owners" study co-author Margarita Gleba, an assistant professor of archaeology at the University of Padua in Italy, told Live Science in an email.

Related: Scythian arrowheads and Bronze Age dwelling uncovered in Ukraine

The team analyzed the leather by using peptide mass fingerprinting, a technique that examines specific proteins in organic samples to determine which kind of animal it was made from.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Their results revealed that Herodotus (who lived circa 484 to 425 B.C.) was accurate in his written assessment of the Scythians' repurposing of human skin.

Herodotus wrote that a Scythian scrapes out human flesh "with the rib of a steer, and kneads the skin with his hands, and having made it supple he keeps it for a hand towel, fastening it to the bridle of the horse which he himself rides, and taking pride in it; for he who has most scalps for hand towels is judged the best man." (Translation by A.D. Godley, 1920.)

"Many Scythians even make garments to wear out of these scalps, sewing them together like coats of skin. Many too take off the skin, nails and all, from their dead enemies' right hands, and make coverings for their quivers," Herodotus wrote.

"Our results appear to confirm Herodotus' [grisly] claim," the research team wrote in the journal article.

Barry Cunliffe, a professor emeritus of European archaeology at the University of Oxford who was not involved with the research, wondered if there could be other reasons, aside from those mentioned by Herodotus, that could help explain why the Scythians used human leather.

"I wonder if what lies behind it is that in possessing some part of what you are hunting, be it human or animal, you gain extra power over them. The belief being that your arrows are guided to your [prey] by their being kept in proximity to their skin?" Cunliffe told Live Science in an email. "Herodotus also says that the Scythians decorated their horses with the heads of their enemies. Could the thought be that the heads not only displayed your valour but guided you to your [prey]?"

The Scythians were not the only people throughout history to use human leather. For instance, binding books with human leather is a practice that has continued from ancient times to the present day. In 2020, a Live Science investigation into the sale of human remains revealed a 1917 edition of the book "Diseases of the Skin," by Dr. Richard Sutton, that a seller on Facebook claimed to have bound with human skin. The seller, who sold the book for $6,500, claimed that they had obtained the human skin from a "retired medical specimen."

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.