Ancient 'Stonehenge' in Golan Heights may not be astronomical observatory after all, archaeologists say

A new analysis of the 6,000-year-old stone circle known as Rujm el-Hiri (also Gilgal Refaim) in Golan Heights suggests that it was not built to observe the heavens.

An ancient and enigmatic stone circle in the Middle East may not be a prehistoric astronomical observatory after all, according to a new study of satellite images. But some of the criticisms may be misguided, an expert on ancient astronomy told Live Science.

Archaeologists think the oldest parts of Rujm el-Hiri (which means "Heap of Stones of the Wildcat" in Arabic) were built more than 6,000 years ago. The site is in the disputed Golan Heights region, which is claimed by both Israel and Syria.

Some earlier investigations proposed that gaps in the stone circle aligned with astronomical events, such as the summer and winter solstices — the shortest and longest nights, respectively — and the monument has been likened to England's Stonehenge.

But the new study's geomagnetic analysis and tectonic reconstruction indicate that the entire landscape around Rujm el-Hiri and the nearby Sea of Galilee has moved over time, according to the study published Nov. 14 in the journal Remote Sensing.

"The Rujm el-Hiri's location shifted from its original position for tens of meters for the thousands of years of the object's existence," the authors wrote — a finding that raises questions about whether it served as an ancient astronomical observatory.

But astronomer E.C. Krupp, director of the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, told Live Science that the dislocation was not quantified in the new research, so it could not determine whether Rujm el-Hiri once showed astronomical alignments.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The ancient stones of Rujm el-Hiri

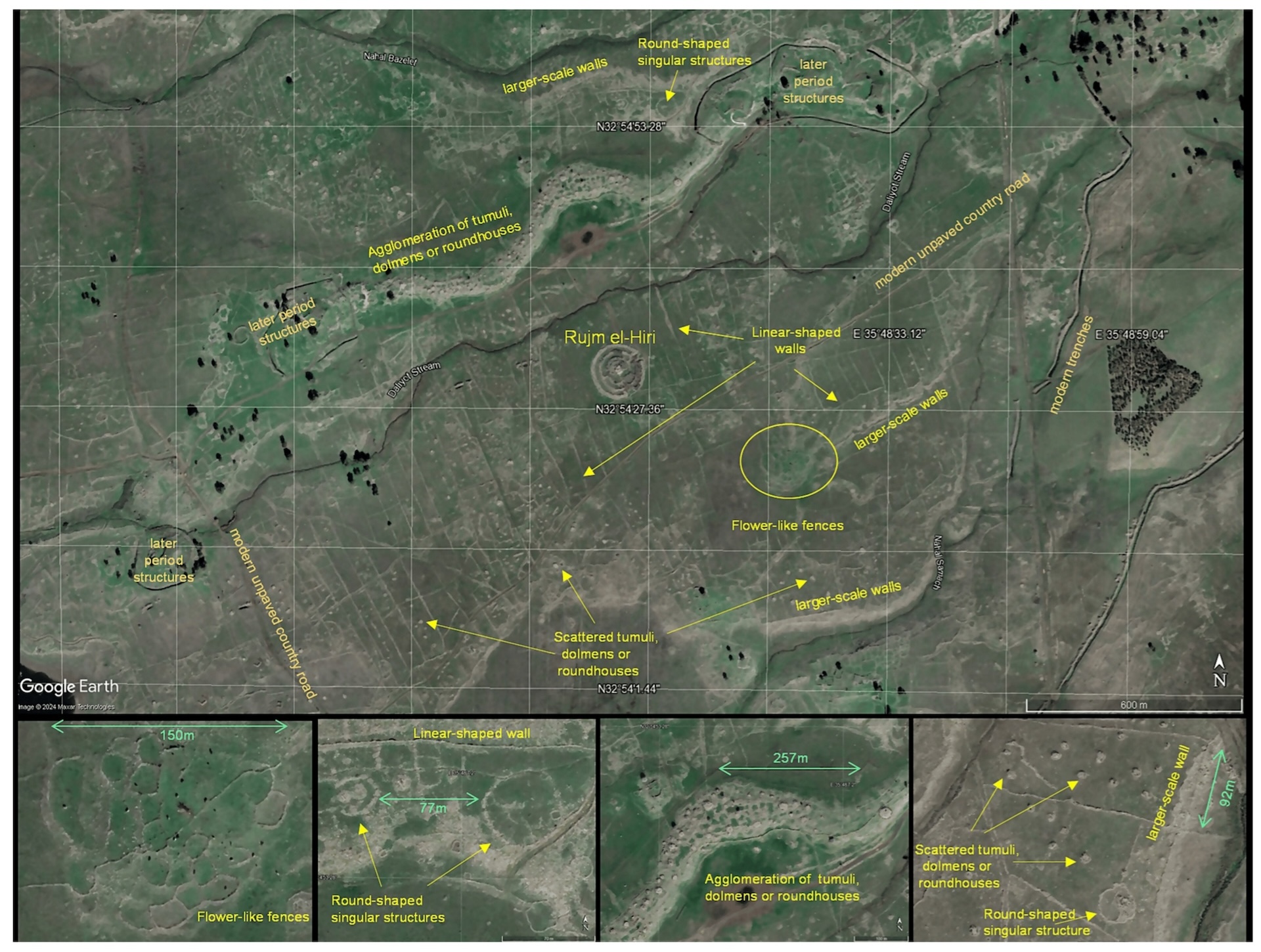

Study lead author Olga Khabarova, a space physicist at Tel Aviv University in Israel, told Live Science that the researchers had used satellite photographs to study Rujm el-Hiri and the surrounding landscape — an especially useful method in remote regions or in politically sensitive territories like the Golan Heights.

The research revealed that Rujm el-Hiri was just one of thousands of prehistoric structures that had been built in the region, including circular structures; enclosures with stone walls that seem to have been used for agriculture; and "tumuli," mounds that may have been used for burials, dwellings or storage.

The ancient stone circle is in the Golan Heights, which was occupied by Israel during the Six-Day War in 1967, but the territory is still claimed by Syria. It consists of several concentric circles, the largest of which is about 500 feet (150 meters) across, that are made from heaps of basalt stones that still stand up to 8 feet (2.5 m) high.

The monument is called Gilgal Refaim in Hebrew (meaning "Wheel of Giants") and is open to the public, but it can be reached only on dirt roads and few people now venture there, Khabarova said. Even when the stone circle was built, the region must have been a rugged highland beside the more favorable shores of the Sea of Galilee, she said.

The latest study used satellite photographs of the ancient stone circle at Rujm el-Hiri to reveal new details about its construction.

The study shows Rujm el-Hiri lies amid of dozens of prehistoric structures, and suggests the entire landscape has rotated and moved geologically since the stone circle was built.

Disputed alignments

Khabarova said the new analysis indicated geological processes had rotated the nearby landscape counterclockwise after Rujm el-Hiri was built, which meant it was unlikely that any valid astronomical alignments could be inferred from its current position.

The analysis of Rujm el-Hiri's location is only a short section of the new paper, but the astronomical angle has been seized upon by several media outlets, including the Times of Israel.

Krupp, an expert on ancient astronomy and the author of "Echoes of the Ancient Skies: The Astronomy of Lost Civilizations" (Dover, 2003), noted that the 1998 paper that proposed astronomical alignments at Rujm el-Hiri had not claimed it was a prehistoric observatory. Instead, that paper argued only that Rujm el-Hiri may have been "a ritual space that incorporated certain celestial alignments to fulfil a symbolic function," he said in an email.

In addition, the latest research paper did not quantify how much the landscape had rotated and so how far it had moved from its original position, so it was not possible to determine if any proposed astronomical alignments were incorrect, Krupp said.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.