Archaeologists in Zambia discover oldest wooden structure in the world, dating to 476,000 years ago

A new finding in Zambia reveals the oldest known wooden construction shaped by the hands of a human ancestor and demonstrates the ingenuity and technical prowess of our ancient relatives.

Archaeologists have discovered the oldest evidence yet of a wooden structure crafted by the hands of a human ancestor. Two tree trunks, notched like Lincoln Logs, were preserved at the bottom of the Kalambo River in Zambia. If the logs' estimated 476,000-year-old age is correct, it means that woodworking might predate the emergence of our own species, Homo sapiens, and highlights the intelligence of our hominin ancestors.

Archaeologists unearthed the logs at Kalambo Falls, on Lake Tanganyika in northern Zambia, a site that has been investigated by scientists since the 1950s. Previous excavations around a small lake just upstream from the falls yielded stone tools, preserved pollen and wooden artifacts that have helped researchers understand more about human evolution and culture over the span of hundreds of thousands of years.

But a new analysis of five modified pieces of wood from Kalambo is pushing back the earliest occupation of the site and giving researchers new insight into the minds of our Middle Pleistocene (781,000 to 126,000 years ago) ancestors.

In a new study published Wednesday (Sept. 20) in the journal Nature, researchers led by Larry Barham, a professor in the Department of archaeology, classics, and Egyptology at the University of Liverpool in the U.K, detail the wooden objects they unearthed. These include two that were found with stone tools below the river and three that were covered in clay deposits above the river level. These wooden artifacts survived over hundreds of thousands of years due to the permanently elevated water table.

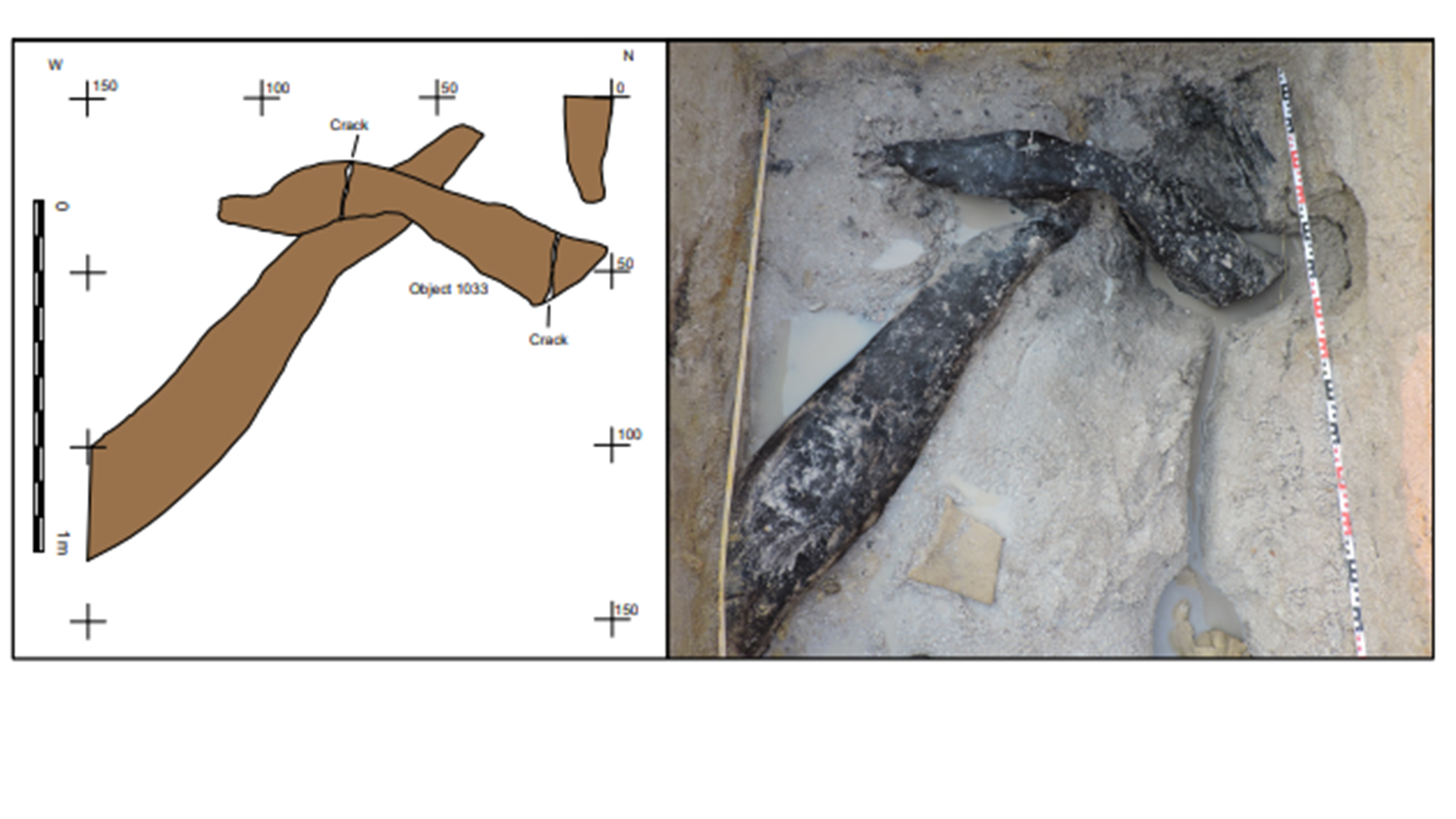

Through luminescence dating of sand samples from the site, which involves measuring how long ago the sand grains were exposed to light, Barham and his colleagues found three clusters: a cut log and a tapered piece of wood dating to 324,000 years ago; a digging stick dating to 390,000 years ago; and a wooden wedge and two overlapping logs dating to 476,000 years ago.

Related: Early human relatives purposefully crafted stones into spheres 1.4 million years ago, study claims

While the small, modified hunks of wood from Kalambo are pretty similar to 400,000-year-old foraging and hunting tools found in Europe and China, the interlocking logs have "no known parallels in the African or Eurasian Palaeolithic," the researchers wrote in the study.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The upper log, recovered from a layer that also had stone tools, measured 55.6 inches (141.3 centimeters) long and was found lying on a large tree trunk at a 75-degree angle.

Both the bottom of the top log and the top of the bottom trunk had evidence of chopping and scraping to make a notch — enabling them to snugly fit together.

"Wood from tree trunks enabled humans to construct large objects," Barham and colleagues wrote in their study, suggesting that their "life in a periodically wet floodplain would be enhanced by constructing a raised platform, walkway or foundation for dwellings."

The newfound objects could push back the dates of the earliest examples of woodworking and help scientists to better understand the technology our hominin ancestors had.

Archaeological evidence of hominin behavior usually comes from artifacts that are nearly indestructible, like stone tools, so the discovery of well-preserved perishable wooden items at Kalambo Falls is important.

"It is unthinkable that hominins would not use wood, given its widespread nature," Shadreck Chirikure, a professor of archaeological science at the University of Oxford who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. The new study shows that "humans and hominins used resources that were available to them," Chirikure added. Chirikure suggested that the very early date of the notched logs "calls for a rethink" of how human cultural and biological evolution is understood.

Scientists previously believed the hominins who lived at Kalambo in the Middle Pleistocene were nomadic foragers with little technological skill, but the new finds show that they were far more intelligent than first thought, the researchers suggested.

"This evidence allows us to consider different materials used by hominins, including those that left traces and those that are perishable," Chirikure said.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Killgrove holds postgraduate degrees in anthropology and classical archaeology and was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.