Brutal lion attack 6,200 years ago severely injured teenager — but somehow he survived, skeleton found in Bulgaria reveals

Extremely rare evidence of a lion attack on a teenage boy's remains suggests the teenager survived the initial trauma but became severely disabled, requiring support from his community.

Around 6,200 years ago, a teenage boy survived a brutal lion attack in what is now Bulgaria — although deep holes in the youngster's skull suggest his brain was badly damaged, a new study finds.

The 16- to-18-year-old may have been hunting when he encountered the lion (Panthera leo), according to the study, which was published Nov. 30 in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. Lions roamed what is now Eastern Europe in the Copper Age (4500 to 3500 B.C.), and cut marks on lion bones from prehistoric settlements on the Black Sea coast suggest humans occasionally ate them.

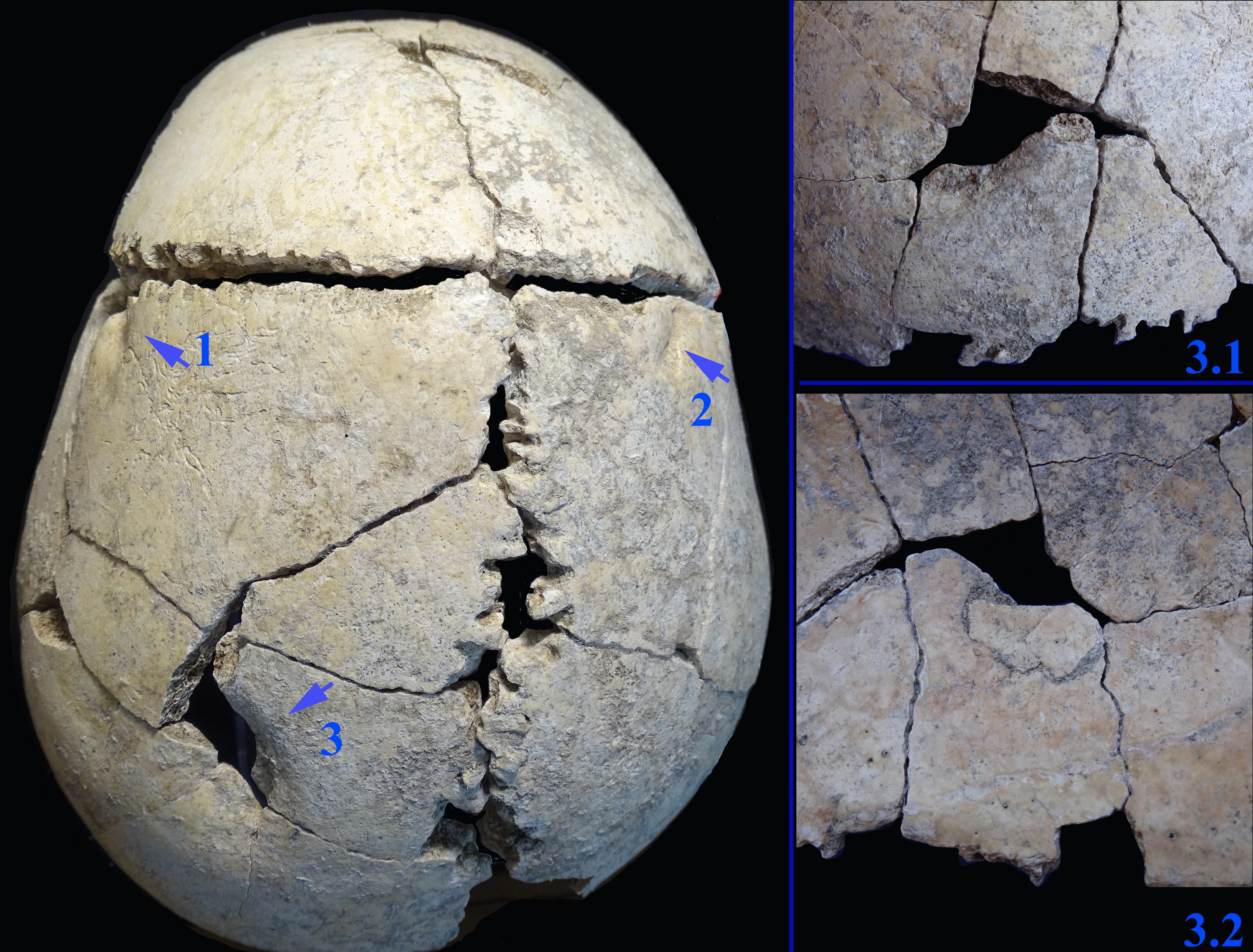

An analysis of the teenager's skeletal remains suggests the lion knocked him to the ground before biting his head multiple times, the researchers said.

"The skull shows a specific pattern of puncture and compressive injuries that are inconsistent with human-made weapons or postmortem damage," study lead author Nadezhda Karastoyanova, an archaeozoologist at the National Museum of Natural History of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (NMNH-BAS), told Live Science in an email. "The size, shape, depth, and spacing of the defects are compatible with trauma produced by the bite of a very large carnivore."

To work out which carnivore was responsible for the attack, the researchers examined various skulls in the NMNH-BAS collection, including lion and bear skulls. Using a special moulding process, they compared different tooth imprints to those found on the teenager's skull. The team also considered the distribution of large carnivores during the Copper Age and found the most likely culprit was a lion.

Prehistoric evidence of lion attacks on humans is extremely rare, but what makes this case even more exceptional is that the teenager survived the initial trauma, Karastoyanova said. There are clear signs of healing on the youngster's skull, suggesting he received medical care after the attack. However, the stage of healing is not very advanced — only two or three months along — so it appears the teenager succumbed to his wounds.

One wound in particular looks like it may have damaged the teenager's meninges — the membranes that line the inside of the skull — leaving the integrity of his brain in a "questionable" state, according to the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The youngster's legs and left arm also sustained deep wounds, possibly damaging his muscles and tendon attachments, Karastoyanova said. "Because the individual was seriously impaired as a result of these injuries, yet survived for a considerable period, it is highly likely that they received care and assistance from others in the community," she said.

The teenager was buried near a prehistoric settlement called Kozareva Mogila, or "Goat Mound," in eastern Bulgaria. Previous discoveries indicate that the inhabitants of Kozareva Mogila tried to treat diseases and performed surgeries on the skulls of living and dead individuals. This suggests they had some level of medical knowledge that may have helped the teenager survive after the attack.

But the youngster likely retained deep scars on his head, arms and legs that changed his appearance considerably, according to the study. He probably needed support for everyday movements, meaning he couldn't do physical labor such as farming, and his neurological functions may have been severely impaired.

Archaeologists found the teenager buried in a crouched position with his hands in front of his face. Measurements indicate he was about 5 feet, 9 inches (175 centimeters) tall. No grave goods were found next to his skeleton, and his burial was deep compared with others at Kozareva Mogila, suggesting he had a low social status and was feared by his community after the attack.

"His individual life experience, possible intimidating behaviour and appearance could have made him an extraordinary and dangerous dead [person], demanding deeper deposition," the researchers wrote in the study.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.