Could Neanderthals talk?

While still the topic of ongoing debate, some scientists think Neanderthals could talk and may have had language.

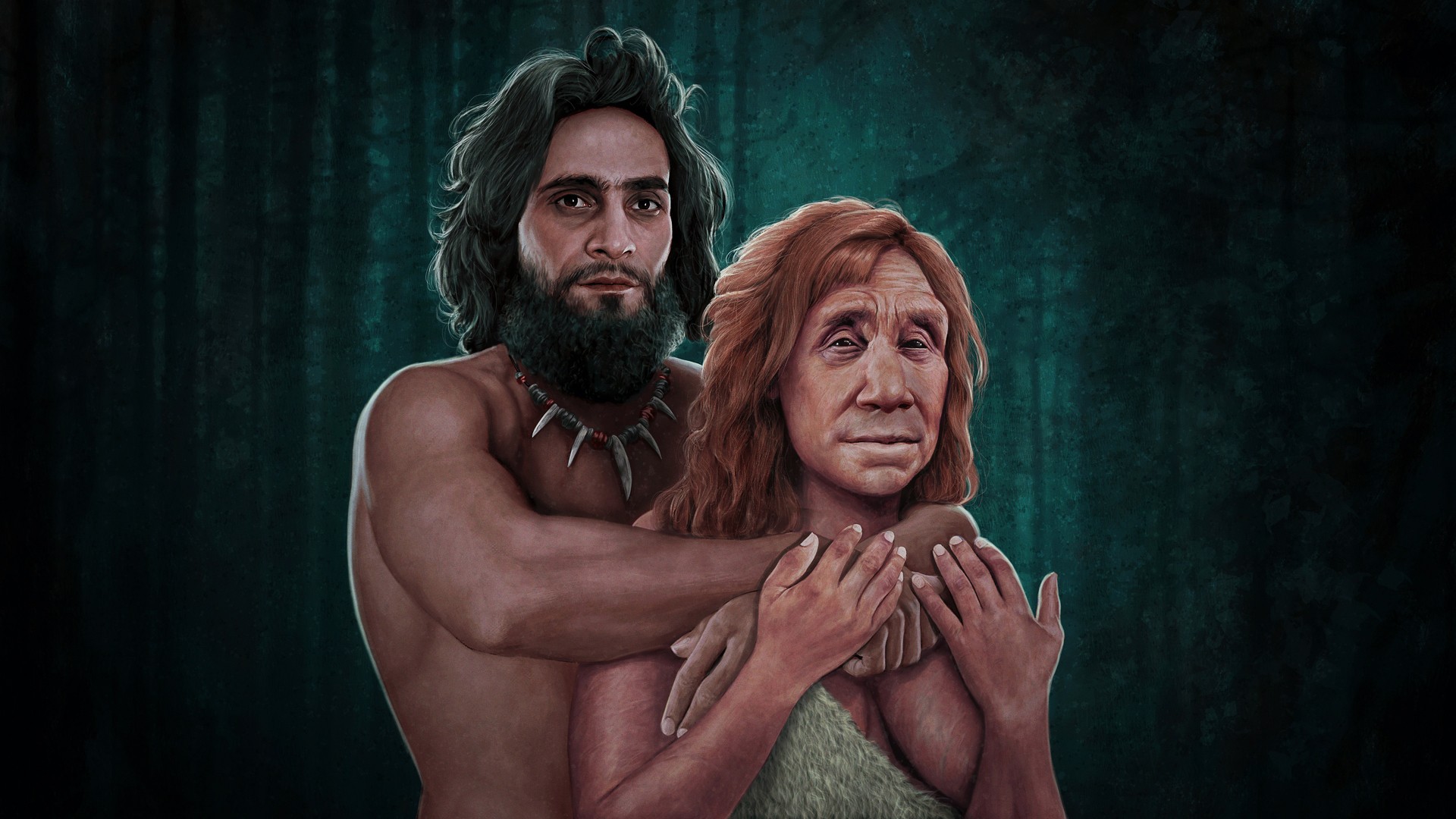

Neanderthals were our closest human relatives, and they had many similarities with anatomically modern humans.

But could Neanderthals talk? Several pieces of evidence suggest they could. But to answer this question, first it's important to distinguish between speech and language.

Speech refers to the ability to verbally say sounds and words. Language is far more complex; it means using those sounds to share ideas.

Some research suggests that speech was acquired long before Homo sapiens and Neanderthals split in the evolutionary tree, sometime between 400,000 and 800,000 years ago.

"Before modern humans split from Neanderthals, the last common ancestor already possessed articulate speech," Andrey Vyshedskiy, a neuroscientist at Boston University, told Live Science.

One of the most convincing pieces of evidence to support this theory is that H. sapiens and Neanderthals share two evolutionary mutations in a gene called FOXP2. This gene is associated with the control of muscles in the mouth and face that help produce speech. Mutations in FOXP2 can cause language deficits in humans.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This suggests Neanderthals could make the movements associated with speech, Vyshedskiy said. But what about language?

By studying modern humans with language impairments, Vyshedskiy and colleagues have proposed that humans evolved through three different language comprehension phenotypes. The most-advanced phenotype, which is what most people have, is syntactic language. Syntactic language conveys complex narratives, uses possessive pronouns, and includes verb tenses and spatial prepositions, he said.

'More Neanderthal than human': How your health may depend on DNA from our long-lost ancestors

Read more:

—What's the difference between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens?

A less-complex language comprehension phenotype, called modifier language, includes an understanding of colors, sizes, and numbers. The least-complex language comprehension phenotype involves only the comprehension of commands, he said.

Command language comprehension phenotype likely evolved earliest in our evolutionary history, soon after the human line split from the chimpanzee line six million years ago, he said. Modifier language gradually evolved 3 million years later, as humans started to manufacture stone tools, followed by syntactic language acquisition a mere 70,000 years ago, he said.

"So Neanderthals were likely speaking like us, but they had a modifier language phenotype," he proposed. “Effectively, Neanderthals may have spoken like a 3-year-old child – well-articulated speech, but no syntactic language comprehension”, he said.

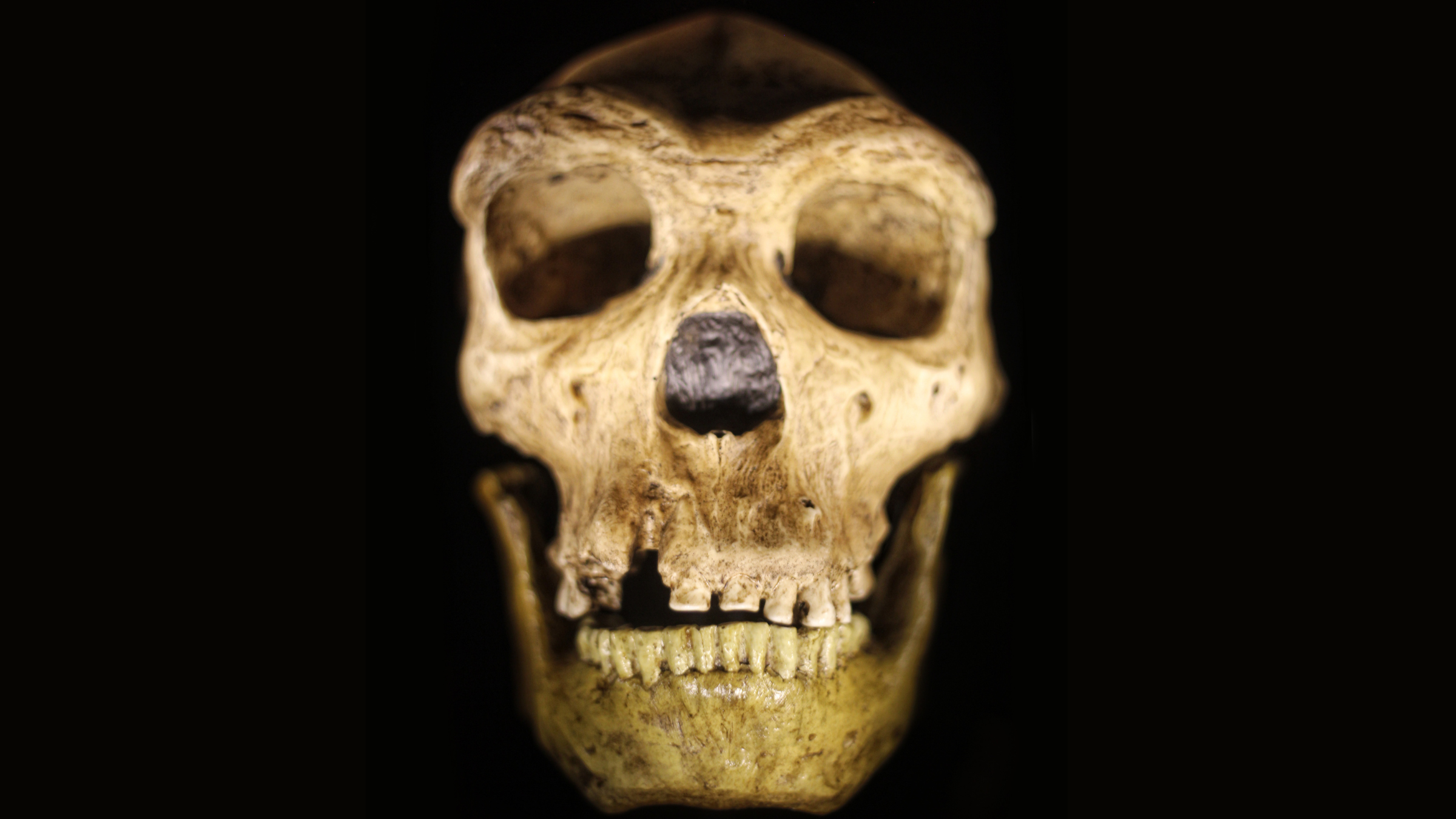

Some fossil research also supports the idea that Neanderthals had language. For example, in a 2021 study in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, researchers took high resolution CT scans of the bones related to hearing abilities. They determined that Neanderthals and modern humans have a greater sensitivity to some sounds in the frequency range of spoken language than do other primates.

"There seems to be a convergence in hearing abilities between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens and presumably language abilities as well," Rolf Quam, a paleoanthropologist at Binghamton University in New York and co-author of the study, told Live Science. Because maintaining sensory organs is energetically costly, most creatures don't evolve sensory abilities they don't use. So if Neanderthals had a modern human hearing pattern, the theory goes, they likely could perceive modern human speech and, therefore, had some form of language, he said.

However, Quam acknowledged that there is some uncertainty about Neanderthals' language abilities.

"Neanderthal language is one of the oldest questions in human evolutionary studies," he said.

For instance, some fossil studies — such as those looking at the hyoid bone in the neck, which is involved in speech production — have been inconclusive, he said.

Still, most experts would probably say Neanderthals had some linguistic ability, Quam said.

"At the very least, they [Neanderthals] had a communication system that was far more complex than [that of] any living ape or primate species," he said.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)