Did humans cross the Bering Strait after the land bridge disappeared?

Evidence suggests that people likely boated across the narrow passage between Russia and Alaska when the crossing was submerged.

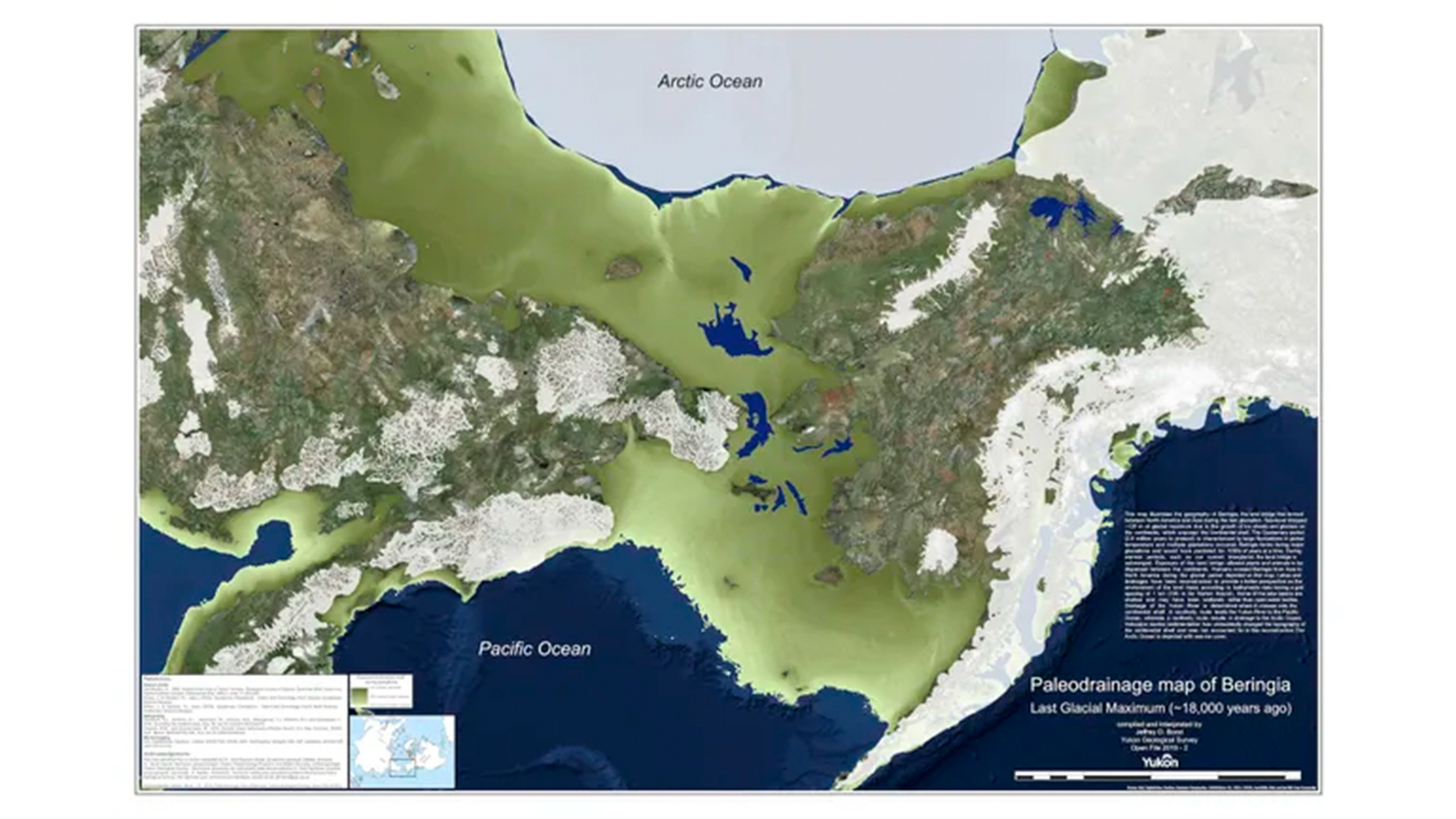

The Bering Land Bridge once connected Russia to Alaska and was a crossing point for some of the first humans to populate the Americas. But during certain periods, the bridge was either impassable or submerged due to sea level rise, seemingly stranding later waves of people on both sides.

But was it possible for early humans to traverse the Bering Strait by boat? And if so, what evidence exists to support their crossings?

According to John Hoffecker, a research fellow emeritus of early human history at the University of Colorado Boulder, recent evidence has shown "beyond a reasonable doubt" that the Bering Land Bridge first emerged around 35,700 years ago before disappearing again about 12,000 years ago, near the end of the last ice age, when glaciers melted and sea level began to rise.

At times, the bridge would have resembled the tundra of northern Alaska and been home to large mammals, Hoffecker said. But that wasn't always the case. Recent research on the region's paleoclimate posits that the bridge was often locked up in impassable ice except during brief windows from 24,500 to 22,000 years ago and 16,400 to 14,800 years ago. Archaeological and genetic evidence supports the idea that early humans, including members of the Clovis culture, may have crossed the land bridge around 14,000 years ago during one of these stretches.

Related: How did humans first reach the Americas?

Successive waves of people streamed across the Bering Strait, including members of a group known as the Paleo-Inuit or Paleo-Eskimo who had appeared in the Arctic by 4,500 years ago and belonged to a culture called the Arctic Small Tool tradition (ASTt). It's less clear, however, how they did so.

Andrew Tremayne, an archaeologist who previously conducted research in Alaska for the National Park Service, said that ASTt peoples were likely advanced mariners, and artifacts found on islands in the Bering Strait and in Alaska today suggest that ASTt people may have been in the area as early as 5,000 years ago. In the Bering Land Bridge National Preserve, in 2013, Tremayne and his team found stone tools from Siberia at an ASTt site dated to about 4,000 years ago.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The people that brought that raw material with them either walked across the frozen Bering Strait or boated," Tremayne told Live Science, noting that even now, the 55-mile-wide (89 kilometers) strait sometimes freezes during the winter. "But based on evidence that they had a rather sophisticated maritime culture, I tend to favor the hypothesis that they boated over."

That idea is bolstered by archaeological sites in North America. Once ASTt people arrived in Alaska, some turned northward, wending their boats between the Canadian Arctic's jumble of islands to become the first people to reach Greenland. Along this punishing route, archaeologists have found evidence of marine mammals being used as food and boats that are similar to the umiaks used by today's Yupik and Inuit peoples in Alaska, Canada and Russia. Made of wood or whale bone covered by seal skin and powered by oars or paddles, a large umiak would have held as many as 20 people.

"I think of these people as some of the most rugged in the history of humans," Tremayne said. "The ASTt people are the first to really start to make a living in that Arctic maritime environment.'

Much later, around 1,000 years ago, ASTt peoples were displaced by the direct ancestors of modern Inuit, Aleut and Yupik peoples who migrated by boat across the Bering Strait from Asia in a later expansion, Tremayne said.

Whether there might have been even earlier water crossings, perhaps by the Clovis people, is a question that may never be answered, Hoffecker said, although the evidence is shifting in that direction. During the last ice age, sea level in the region that includes the land bridge — known as Beringia — was significantly lower, and hundreds of miles of coastline was exposed along Siberia, Alaska and other parts of North America. Today, any coastal sites that early humans might have used during their travels south are buried beneath sea and sediment.

But even as the story continues to unfold, Hoffecker said he has become "a strong believer in the Pacific Northwest coast as the main root of migration for the initial movement of people out of Beringia and into the Americas."

Amanda Heidt is a Utah-based freelance journalist and editor with an omnivorous appetite for anything science, from ecology and biotech to health and history. Her work has appeared in Nature, Science and National Geographic, among other publications, and she was previously an associate editor at The Scientist. Amanda currently serves on the board for the National Association of Science Writers and graduated from Moss Landing Marine Laboratories with a master's degree in marine science and from the University of California, Santa Cruz, with a master's degree in science communication.